Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

EMPOWERING FAMILIES THROUGH PSYCHOEDUCATION: A STUDY

ON CAREGIVERS OF CHILDREN WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES

Swati Kumari1& Manisha Kiran2

1*PhD Scholar, Department of Psychiatric Social Work (PSW), Ranchi Institute of Neuro- Psychiatry

and Allied Sciences (RINPAS), Kanke, Ranchi, Jharkhand. 2Associate Prof. and Head, Department

of Psychiatric Social Work (PSW), Ranchi Institute of Neuro-Psychiatry and Allied Sciences

(RINPAS), Kanke, Ranchi, Jharkhand.

*Correspondence: Swati Kumari, e-mail: Swatikri2710@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities often encounter significant challenges that can affect their family’s sense of empowerment. Psychoeducation has been recognized as a valuable tool to provide caregivers with the knowledge, skills, and support they need to enhance their caregiving abilities and overall family empowerment. Aim: This study aimed to evaluate the impact of a brief psychoeducation module on the family empowerment of caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities. Method: The study was conducted at the Ranchi Institute of Neuro-Psychiatry & Allied Sciences (RINPAS), Ranchi. A pre-test and posttest design was used with 20 caregivers, who were divided into an experimental group (n=10) and a control group (n=10). The experimental group underwent 10 sessions of psychoeducation over 10 weeks, in addition to their usual treatment, while the control group only received their usual treatment. The Family Empowerment Scale (FES) was utilized to evaluate empowerment levels before and after the intervention. Results: The study showed that the experimental group experienced significant improvements in family empowerment across all domains (“About Your Family,” “About Your Child’s Services,” and “About Your Involvement in the Community”) compared to the control group. There were no significant differences in sociodemographic variables between the groups. Conclusion: The study highlights the efficacy of structured psychoeducation in bolstering the empowerment of caregivers through the provision of vital knowledge, coping strategies, and support. These results indicate that psychoeducation is an invaluable intervention for enhancing the care and overall well-being of families responsible for children with intellectual disabilities.Keywords:Psychoeducation, family empowerment, caregivers, intellectual disabilities.

INTRODUCTION

Caring for children with intellectual disabilities presents unique challenges that can significantly impact the well-being of families. These challenges often extend beyond the child’s immediate needs, affecting the entire family’s emotional, social, and economic stability and dynamic (Douglas et al. 2016; Dada et al. 2020). Families frequently encounter additional issues, such as a lack of knowledge, self-stigma, and underutilization of available services, which can further exacerbate the caregiving burden (Lakhan, R., & Sharma, 2010). It’s important to recognize that a lack of understanding about intellectual disabilities can result in ineffective management of a child’s needs. This can stress family members who may struggle to provide proper care without the necessary knowledge. This can lead to feelings of helplessness and frustration. The stigma surrounding intellectual disabilities can make these issues even worse, as it can lead to feelings of shame and isolation, making it difficult for families to seek the support and services they need (Brown, 1997). On top of that, accessing services is often made more challenging by factors such as a lack of awareness about available services, logistical obstacles, and previous negative experiences with service providers (Emerson & Hatton, 2007). The empowerment approach helps to reduce burdens by providing necessary information, skills, and support, and by instilling hope and capability. Educating caregivers and connecting them with supportive networks transforms their experiences and enables them to cope more effectively, advocating for their loved ones and themselves. This holistic approach leads to better caregiving and a stronger, more resilient family dynamic (Chiu et al. 2006). Parental empowerment entails providing parents and caregivers with the knowledge and skills necessary to support children with disabilities. When parents are empowered, they gain a deep understanding of their child’s health conditions or disabilities. This understanding allows them to advocate for their child’s needs, work collaboratively with healthcare providers and educators, and make well-informed decisions. Psychoeducation is an important tool for empowering families of children with intellectual disabilities. It provides comprehensive knowledge, coping strategies, and resources to reduce psychological burdens and enhance caregiving skills. According to Bäuml and Pitschel-Walz (2008), psychoeducation is “systematic, structured, didactic information about the illness and its treatment, including emotional aspects, to help patients and their family members cope with the illness. This study investigates how psychoeducation affects the empowerment of families caring for children with intellectual disabilities. The research examines the outcomes of caregivers who have participated in psychoeducational programs to identify the benefits and areas for improvement in such interventions. The study conducted by McCallion et al. (2024) carefully analyzed the effectiveness of a support group intervention for grandparents who care for children with developmental disabilities and delays. A total of 97 grandparents from three agencies in New York City participated in the study and were assigned to either the treatment group or the waitlist control group. The intervention was based on the stress and coping model and drew upon extensive literature on supporting family caregivers. The results showed that the participants in the treatment group experienced significant reductions in symptoms of depression and increases in their sense of empowerment and caregiving mastery. In a study by Fujioka et al. (2014), caregivers from 19 families were interviewed. The analysis identified three key categories in the empowerment process: Isolation in Child Rearing, Exchanges with Others, and Establishment of a Rearing System. The core category that emerged was the Continuation of Appropriate Rearing. These findings emphasize the central role of continuous and appropriate care in caregiver empowerment, highlighting social isolation, the importance of social exchanges, and the development of a structured care system. Goluboviæ et al. (2021) conducted a comparative study with a quantitative, descriptive analysis of 99 families. The study included 57.6% parents of children with developmental disabilities and 42.4% parents of typically developing children. Results indicated that parents of children with developmental disabilities had lower levels of family empowerment, especially in attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. The lowest empowerment was observed in the Community domain.. An Indian study by Lakhan and Sharma (2010) reported in his study that participants have lacked access to information and appropriate services, and many held misconceptions about intellectual disabilities, often treating their children punitively. This behavior was more prevalent in the tribal group. Additionally, some parents attributed their children’s disabilities to sins from past lives rather than considering factors like poor nutrition or birthrelated issues. According to Nachshen and Minnes (2005), parents of children with developmental disabilities (DD) experienced elevated levels of child behavior problems, stress, and lower well-being in contrast to parents of children without DD. Nevertheless, they also reported receiving greater social support. The study highlighted a direct relationship in which parent well-being and available resources mediated the impact of child behavior problems (the stressor) on empowerment outcomes.OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study is to examine the effects of providing brief psychoeducation to caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities on family empowerment.METHODS & MATERIALS

Venue of the study:The proposed study was conducted at Ranchi Institute of Neuro-Psychiatry & Allied Sciences (RINPAS) in Kanke, Ranchi.

Design of the study:

The present study employed a hospital-based intervention design using a pre-test and posttest design. The study included an experimental group receiving both treatment as usual and psychoeducation, alongside a control group receiving only treatment as usual. The experimental group participated in a total of 10 sessions over 10 weeks.

Sample:

In this study, 20 caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities participated. The experimental group consisted of 10 caregivers, while the control group of 10 caregivers. All participants were selected from RINPAS Ranchi using purposive sampling techniques.

Inclusion criteria for the caregiver of children with Intellectual disability:

· Caregivers of children, diagnosed with Intellectual disability as per ICD-10 DCR (Moderate and Severe level).

· The age range of the children is 6-10 years, comprising both sexes.

· Caregivers actively involved and living in the same house for more than 2 years.

· The age range of caregivers between 25 to 40 years.

· Caregivers can read and write.

· Caregivers who provide written

informed consent and are willing to participate voluntarily

Tool:

Family Empowerment Scale (Koren, DeChillo, & Friesen, 1992):

The Family Empowerment Scale (FES) is a 34-item tool that measures how empowered a family feels. It uses a Likert-type response format, where participants rate each item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a higher level of family empowerment. The scale is based on two dimensions: the level of empowerment (family and service system, and community) and the expression of empowerment (attitude, knowledge, and behavior). In this study, only the level of empowerment dimension (family, service, and community) is used. Subscale scores on the FES are calculated by adding up the respective item scores. The empowerment scores for Family and Service System range from 12 to 60, while the score for Community ranges from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher levels of empowerment. The FES has demonstrated reliability in terms of internal consistency and test-retest reliability, as well as validity through high agreement between independent raters based on its twodimensional framework. The internal consistency alpha for the Family and Service System subscale is reported to be 0.87, and for the Community subscale, it is 0.88.

PROCEDURE

This study selected 20 caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities using purposive sampling, based on predefined inclusion criteria. Participants were randomly assigned to either an experimental group or a control group, each consisting of 10 participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their participation. At baseline, all participants completed a sociodemographic datasheet and the Family Empowerment Scale assessment. The experimental group underwent a 10-session brief psychoeducation module in addition to their usual treatment, while the control group received only their usual treatment. Following the completion of the 10 sessions, the study concluded its sessions. Participants were reassessed on family empowerment after the termination of the psychoeducation intervention.

The module of brief Psychoeducation to the caregivers of children with Intellectual disability: Intervention description:

RESULTS

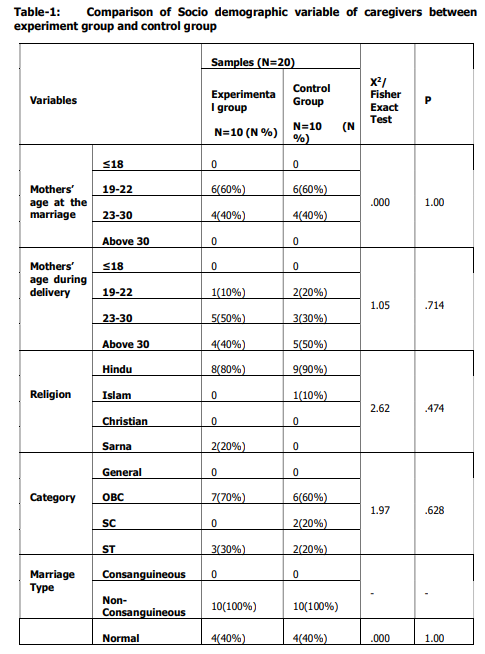

Table 1 compares demographic characteristics of caregivers in a study on children with intellectual disabilities. Both experimental and control groups predominantly had mothers married between ages 19-22 and delivering their first child between ages 23-30. Most were Hindu and belonged to the OBC category in both the group. All marriages were nonconsanguineous, and most of cesarean deliveries in both groups. Mothers were primarily housewives; fathers’ occupations varied, with more daily wage earners in the control group. Statistical tests found no significant differences between groups.

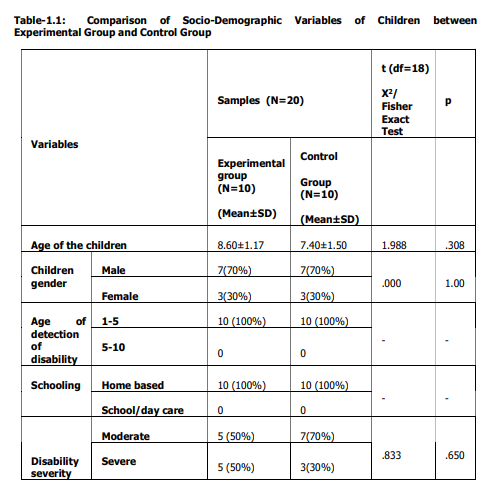

Table 1.1 compares socio-demographic

variables of children in an experimental group

and a control group. The mean age of children

was 8.60±1.17 in the experimental group and

77.40±1.50 in the control group, with no

significant age difference. Gender distribution

was equal in both groups. All children were

identified with disabilities between ages 1-5

and received home-based schooling.

Statistical tests found no significant

differences between the groups.

Table 2 compares family empowerment

between the experimental and control groups

at baseline across three domains using the

Mann-Whitney U test. There was no significant

difference in the “about your family” domain

(U = 46.00, p = .759). Similarly, in the “about

your child’s Services” domain, no significant

difference was found (U = 47.50, p = .849).

In the “about your involvement in the

community” domain, no significant difference

was observed (U = 39.50, p = .407). These

findings indicate comparable levels of family

empowerment between the groups at baseline.

Table 3 compares the impact of a

psychoeducation intervention on family

empowerment between an experimental

group and a control group of caregivers of

children with intellectual disabilities. The experimental group showed significantly

higher scores than the control group in all

domains: “about your family” (U = 0.00, p =

.000), “about Your Child’s Services” (U = 0.00,

p = .000), and “about your involvement in the

community” (U = 9.00, p = .002). These

findings indicate that the psychoeducation

intervention had a substantial positive effect

on family empowerment across all domains

for the experimental group

DISCUSSION

The study investigated the impact of a psychoeducation intervention on family empowerment among caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities, Contrasting the experimental group that underwent the intervention with the control group that did not. Initial analysis found no significant differences in sociodemographic variables between caregivers and children in both groups, indicating they were comparable at the study’s outset. This similarity suggests that any observed disparities in family empowerment likely stem from the psychoeducation module rather than preexisting sociodemographic factors, underscoring the intervention’s effectiveness in enhancing family empowerment. The study findings revealed significant disparities in family empowerment across all domains—namely, “About Your Family,” “About Your Child’s Services,” and “About Your Involvement in the Community”—between the experimental and control groups. These differences underscore the effective impact of the psychoeducation module in enhancing caregivers’ sense of empowerment in various caregiving aspects. This echoes prior research suggesting that targeted educational interventions can equip caregivers with essential knowledge, skills, and support for managing challenges linked to caring for children with intellectual disabilities (Peshawaria, 1992; Girimaji, 2008; Bhattacharjee et al., 2017). The outcomes highlight the significance of structured psychoeducation in improving caregivers’ understanding of disabilities and available resources, as well as bolstering their ability to manage stress and advocate for their children effectively (Srivastava & Panday, 2016).

The study investigated the impact of a psychoeducation intervention on family empowerment among caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities, Contrasting the experimental group that underwent the intervention with the control group that did not. Initial analysis found no significant differences in sociodemographic variables between caregivers and children in both groups, indicating they were comparable at the study’s outset. This similarity suggests that any observed disparities in family empowerment likely stem from the psychoeducation module rather than preexisting sociodemographic factors, underscoring the intervention’s effectiveness in enhancing family empowerment. The study findings revealed significant disparities in family empowerment across all domains—namely, “About Your Family,” “About Your Child’s Services,” and “About Your Involvement in the Community”—between the experimental and control groups. These differences underscore the effective impact of the psychoeducation module in enhancing caregivers’ sense of empowerment in various caregiving aspects. This echoes prior research suggesting that targeted educational interventions can equip caregivers with essential knowledge, skills, and support for managing challenges linked to caring for children with intellectual disabilities (Peshawaria, 1992; Girimaji, 2008; Bhattacharjee et al., 2017). The outcomes highlight the significance of structured psychoeducation in improving caregivers’ understanding of disabilities and available resources, as well as bolstering their ability to manage stress and advocate for their children effectively (Srivastava & Panday, 2016).

CONCLUSION

The findings suggest that integrating psychoeducation into caregiving support programs is crucial for boosting family empowerment among caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities. Such interventions hold promise for enhancing overall family well-being and elevating the quality of care provided to children with special needs.

The findings suggest that integrating psychoeducation into caregiving support programs is crucial for boosting family empowerment among caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities. Such interventions hold promise for enhancing overall family well-being and elevating the quality of care provided to children with special needs.

REFERENCES:

Bäuml, J., Froböse, T., Kraemer, S., Rentrop, M., & Pitschel-Walz, G. (2006). Psychoeducation: a basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their f a m i l i e s . S c h i z o p h r e n i a bulletin, 32(suppl_1), S1-S9. Bhattacharjee, d. (2017). Effectiveness of psychoeducation on psychological wellbeing and self-determination in key caregivers of children with intellectual disability (doctoral dissertation, ranchi university). Brown, R. I. (Ed.). (1997). Quality of life for people with disabilities: Models, research and practice . Nelson Thornes. Chiu, M. Y. L., Wei, G. F. W., & Lee, S. (2006). Personal tragedy or system failure: A qualitative analysis of narratives of caregivers of people with severe mental illness in Hong Kong and Taiwan. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 52(5), 413-423. Dada, S., Bastable, K., & Halder, S. (2020). The role of social support in participation perspectives of caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities in India and South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(18), 6644. Douglas, T., Redley, B., & Ottmann, G. (2016). The first year: The support needs of parents caring for a child with an intellectual disability. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(11), 2738- 2749. Emerson, E., & Hatton, C. (2007). Mental health of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Britain. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 493-499. Fujioka, H., Wakumizu, R., Okubo, Y., & Yoneyama, A. (2014). Empowerment of families rearing children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities at home. Medical and health science research: Bulletin of Tsukuba International University, 5, 41-53. Girimaji, S. C. (2008). Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of children with mental retardation. Indian J Psychiatry, 132(1), 43-67. Goluboviæ, Š., Milutinoviæ, D., Iliæ, S., & Ðorðeviæ, M. (2021). Empowerment practice in families whose child has a developmental disability in the Serbian context. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 57, e15-e22. Lakhan, R., & Sharma, M. (2010). A study of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) survey of families toward their children with intellectual disability in Barwani, India. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 21(2), 101- 117. McCallion, P., Janicki, M. P., & Kolomer, S. R. (2004). Controlled evaluation of support groups for grandparent caregivers of children with developmental disabilities and delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 109(5), 352-361. Nachshen, J. S., & Minnes, P. (2005). Empowerment in parents of school aged children with and without developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(12), 889-904. Peshawaria, R. (1992). Behavioural approach in teaching mentally retarded children. A manual for teachers. Secunderabad: National Institute for the Mentally Handicapped. Srivastava, P., & Panday, R. (2016). Psychoeducation an effective tool as treatment modality in mental health. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(1), 123-130.

Bäuml, J., Froböse, T., Kraemer, S., Rentrop, M., & Pitschel-Walz, G. (2006). Psychoeducation: a basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their f a m i l i e s . S c h i z o p h r e n i a bulletin, 32(suppl_1), S1-S9. Bhattacharjee, d. (2017). Effectiveness of psychoeducation on psychological wellbeing and self-determination in key caregivers of children with intellectual disability (doctoral dissertation, ranchi university). Brown, R. I. (Ed.). (1997). Quality of life for people with disabilities: Models, research and practice . Nelson Thornes. Chiu, M. Y. L., Wei, G. F. W., & Lee, S. (2006). Personal tragedy or system failure: A qualitative analysis of narratives of caregivers of people with severe mental illness in Hong Kong and Taiwan. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 52(5), 413-423. Dada, S., Bastable, K., & Halder, S. (2020). The role of social support in participation perspectives of caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities in India and South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(18), 6644. Douglas, T., Redley, B., & Ottmann, G. (2016). The first year: The support needs of parents caring for a child with an intellectual disability. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(11), 2738- 2749. Emerson, E., & Hatton, C. (2007). Mental health of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Britain. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 493-499. Fujioka, H., Wakumizu, R., Okubo, Y., & Yoneyama, A. (2014). Empowerment of families rearing children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities at home. Medical and health science research: Bulletin of Tsukuba International University, 5, 41-53. Girimaji, S. C. (2008). Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of children with mental retardation. Indian J Psychiatry, 132(1), 43-67. Goluboviæ, Š., Milutinoviæ, D., Iliæ, S., & Ðorðeviæ, M. (2021). Empowerment practice in families whose child has a developmental disability in the Serbian context. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 57, e15-e22. Lakhan, R., & Sharma, M. (2010). A study of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) survey of families toward their children with intellectual disability in Barwani, India. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 21(2), 101- 117. McCallion, P., Janicki, M. P., & Kolomer, S. R. (2004). Controlled evaluation of support groups for grandparent caregivers of children with developmental disabilities and delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 109(5), 352-361. Nachshen, J. S., & Minnes, P. (2005). Empowerment in parents of school aged children with and without developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(12), 889-904. Peshawaria, R. (1992). Behavioural approach in teaching mentally retarded children. A manual for teachers. Secunderabad: National Institute for the Mentally Handicapped. Srivastava, P., & Panday, R. (2016). Psychoeducation an effective tool as treatment modality in mental health. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(1), 123-130.

Conflict of interest: None

Role of funding source: None