Background: Each emerging country’s fertility rate is falling, and as a result, female labor force

participation has shifted. The role of women in achieving the demographic dividend is a problem

that emerging countries must address. As a result, in order to reap the benefits from the

demographic dividend, gender equality in the workplace must be prioritized. Aim: To study the

association between the fertility rate and female work participation in Manipur. Methods and

Materials: The Indian Census across the years 1991 to 2011 was accessed, and the descriptive

statistics were employed. Results: It was found that among the main workers, Manipur (13.06%)

had a substantially lower proportion of the 10-15 years age group than India (35.35%) in 1991,

implying that premature married women were more widespread in India than in Manipur. Married

women who did not work (housewives) increased further throughout all census years in Manipur

(5.47%) and India (14.19%). The main workers were often more concentrated in urban areas

than in rural areas in both Manipur and India, indicating that there are more job prospects in

urban areas. From 1991 to 2011, Manipur and India saw a general trend of dropping fertility

rates across all age groups and economic activity categories. Conclusion: The female labour

participation rate is very low when compared to many advanced economies, showing that there

is still tremendous space for growth in terms of gender equality and women’s economic

empowerment.

The fertility level of each developing country

is declining, and as a result, there has been

a change in the behaviour of females to

participate in the labour force. Women’s role

in gaining the opportunity for the demographic

dividend is an issue that is pertinent to

developing countries. The population boom in

working-age individuals has resulted in a rise

in the labour force participation rate during

the demographic transition caused by the drop

in the fertility rate. In addition, there is also

an increase in the number of women

participating in the labour force due to the

smaller family size brought up by the dropping

fertility rate (Torres, 2015). Women’s

involvement in the workforce has contributed positively t o the Gross Domestic Product

(Aydin et al., 2019). As much as 12.2 percent

more GDP may be generated if gender

differences in labour force participation were

reduced (Marone, 2016). Therefore, to reap

the benefits of the demographic dividend,

gender equality in the workforce needs to be

given particular attention.

Variations in fertility rates cause differences

in population growth rates and age-structured

population scenarios among countries. There

may be an increase in the working-age

population, but there will be an imbalance in

numbers between men and women. Again,

there would be an uneven distribution of

people entering the labour force. A higher

level of female labour force involvement in

an economy may provide a more significant

advantage in capturing the demographic

dividend. To this, Wodon et al. (2020) stated

that “if women were earning as much as men,

women’s human capital wealth could increase

by more than half globally ……”. Hence,

disparities in women’s employment rates may

contribute to the differences in economic

growth rates among nations. Higher economic

growth for a country depends on a higher

participation rate of females. Narrowing the

gap in labour force participation between

males and females will boost economic

growth.

Besides, the differences in education level

attained by females and the fertility level

acquired may impact women’s participation

in the workforce. A woman’s entry into the

workforce depends on how many children she

has. There is a long-run co-integration

between the female labour force participation

rate and total fertility rate, and both influence

each other through the interaction effect of

female age at first marriage, per capita gross

domestic product, and infant mortality rate (Ali

& Dhillon, 2022). Attracting more women into

the labour force requires equal access to

education and the opportunity to gain the

skills necessary to compete in the labour

market.

However, they face certain challenges in

attaining decent work. How they are engaged

in the labour force and how their unique

values and constraints must be assessed to

get the opportunity of demographic dividends

are now issues.

Numerous scholars have attempted to assess

the connection between fertility and female

labour force participation globally. Most of the

analysis remarks a significant connection

between fertility and the employment of

women influenced by other auxiliary variables

(Ahn and Mira, 2000, and Majbouri,2019).

Fertility plays a significant role in women’s

decisions to enter the labour market, with a

negative impact on female labor force

participation overstated when fertility is not

considered (Ukil, 2015). Having a third child

or more has an unfavorable effect on labor

market participation, with an average

decrease of 7.4 percentage points. This can

lead to poverty traps and economic inequality

for low-skilled women in informal employment

(Tumen & Turan, 2020). Role Incompatibility

Approach articulates that there is an inverse

relationship between female employment and

fertility, only in a condition where the trade

off between a mother’s duty and work is not

accommodated duly (Mason & Palan, 1981).

However, fertility and employment positively

correlate when the economies have limited

employment chances. As the rate of women

finding jobs rises, the direction of the

association between employment ratios and

fertility rates across nations may vary (Fang

et al.,2013; Krishnan, 1991).

The decline in fertility reduces population

growth and increases the ratio of working age to the total population, augmenting female

labour force participation. Fertility hurts

female labour force participation largely in the

age 20-39, but persistent cohort participation

exists over time (Bloom et al., 2007).

Economic growth in developing nations

encourages women to enter the labour force

only when labour market regulations actively

support women’s entry (Luci, 2009). On the

other hand, entitlement to social security

benefits, having children in the home, and

long-term illness all reduced participation.

Patriarchal household cultures adversely

impact the participation and productivity of

women in the workforce. However, the

outcome varies somewhat according to the

type of job and the work site (urban vs. rural)

(Sarkhel & Mukherjee, 2014). A tactic to

lessen the “double burden” of work for women

appears to be decreased labour participation

and growing income levels. The patriarchal

society restricts women’s options to home

pursuits rather than paid employment by

elevating domestic activities and stigmatizing

paid jobs (Abraham, 2013).

Fertility and education also significantly

influence the degree of female labour force

participation. Higher-educated women have

fewer offspring than lower-educated women

in both developed and developing nations

(Kim, 2016). Thus, female education has a

positive effect, and the fertility rate has a

negative effect on female labour force

participation (Altuzarra et.al, 2019). Both

personal choices and policy influence

women’s decisions to labour on the extensive

and intensive margins.

Many earlier studies also highlighted the

association between fertility and types of

employment (Kinoshita & Guo, 2015; Aydin et

al., 2019). And other studies also addressed

the relationship between fertility, wage,

religion, and female labour force participation

worldwide (Siegel, 2012; Fatima & Sultana,

2009; Abdou & Shalaby, 2019; Alam et al.,

2018)

Despite significant economic growth, the

proportion of Indian women working in

domestic, non-remunerative occupations has

risen, while India’s FLFP has fallen since the

1980s (Afridi et al., 2018; Chaudhary & Verick,

2014). In India, women’s labor force

involvement and fertility are not entirely

associated. The long-run co-integration of

female labor force participation rate and total

fertility rate is influenced by the interaction

impact of female age at first marriage, per

capita GDP, and infant mortality rate (Ali &

Dhillon, 2022). Tiwari et al. (2022) argue that

increasing the number of children born

decreases income and female labor force

participation in India by analyzing the

influence of intertemporal fluctuations in

reproductive behaviour on outcomes for

women in the labour market. The data shows

that women with more than three children had

a 3.5% higher likelihood of exiting the labor

force than their counterparts with two or

fewer children. Again, on segmented analyses

by caste, economic status, educational status,

and region, the probability of leaving the labor

force due to changes in fertility varies by

region, and it was higher for non-poor women

with primary to secondary education and

those from socially disadvantaged castes than

for poor, uneducated, and socially

advantageous women. Mahapatro (2013),

who investigated the causes of the decline in

female labor force participation in India,

found that changes in age and time can explain

a major drop in labour force participation.

Women’s labor-force participation has been

declining across all ages and educational

levels. Longer educational duration tends to

reduce female engagement in younger

generations. Workforce participation rates

were strongly connected with socioeconomic

and demographic criteria other than gender, such as age, education, caste, religion, place

of residence, family size, etc. These

considerations must be considered to fully

reap the benefits of the region’s demographic

dividend (Mawkhlieng & Algur, 2021). These

studies show that reducing fertility alone will

not enhance female labor force participation

in India.

In the last 25 years, female labour force

participation in India has declined. Between

1983–1984 and 2011–2012, India’s female

labour force participation rate fell by 25%

(Lahoti & Swaminathan, 2013). This drop in

female LFPR can be explained mainly by

increases in the education levels of women

and men in their households (Afridi et al.,

2018).

The employment transition of Indian women

of working age not only left the workforce at

a concerning rate, but they were also

participating in it less. According to Sarkar et

al. (2017), women’s entry and leave

possibilities decrease when the income of

other household members increases. The

critical discovery that household wealth and

income have a major impact may help explain

why, despite economic progress, female

labour force participation may not rise over

time. Furthermore, the study discovers that

a sizable public workfare program

considerably lowers the rate women leave the

workforce.

On the other hand, given that institutional

childcare is practically non-existent in Indian

society, Das & Zumbyte (2017) claimed that

women’s job decisions are increasingly being

influenced by the issue of caring for little

children. So, mothers’ employment was

negatively impacted by having small children

at home, a worsening trend. Additionally,

having older children and women over 50

years was positively correlated with women’s

employment. As such, Sorsa et al. (2015)

exclaimed that there was a negative

correlation between female labour force

participation and income and education levels

of the women. In this regard, apart from a

dearth of jobs, their study proclaimed that

societal and cultural restrictions hinder

women from joining the workforce.

Infrastructural constraints, financial

accessibility, labour laws, and rural

employment programs are additional variables

that persist in the issue.

When comparing the average position of

women across India to that of the North

Eastern area, Das (2013) concluded that

women in the region had a better overall

situation than women across the country. The

indicators depicted that women’s freedom of

mobility, self-control, and power to impact

change in NER were severely limited. The

survey also found that NER states had greater

rates of married women participating in

household decision-making than the national

norm. Certain NER states had observed an

increase in FWPR. Women in the Northeast

had a higher working-age population rate than

the national average, although it was typically

lower than men. Female labor participation

was increasing in all states of Northeast India,

except for Assam, and it is now more

significant than the national average. The

study found that Northeast India’s average

FLPR was higher than the national average

due to the presence of tribal dominant states

i n the region. Women’s labor-market

involvement will be increased by increasing

job opportunities based on education and

removing gender-based compensation

discrimination (Kaur, 2016). Higher labor

participation does not automatically result in

improved outcomes; it necessitates more

education and/or assets (Srivastava &

Srivastava, 2010). While education may not

influence a woman’s decision to work, it was

the most essential element in identifying

higher-quality non-agricultural jobs for working women. Women can enter non

agricultural jobs because of their autonomy,

which was characterized as their freedom to

manage their land, travel, and participate in

self-help groups.

While there has been a noticeable increase

in women’s work participation rates in the

north-eastern Indian states, women’s work

participation rates remain significantly lower

than men’s (Pegu, 2015). Regarding women’s

engagement in the workforce, there appears

to be a difference between rural and urban

areas. The northeast states had seen a rise

in women’s literacy, which benefited the

political, social, and ideological domains. All

of this resulted from the beneficial

developments that the area had seen as a

result of training and education. The

percentage of women participating in the

labour sector for rural and urban Assam was

dropping.

As per reviews, a few studies related to

fertility by age groups and female labour force

participation in the northeastern states of

India. The nature of policies and programmes

relating to the female labour force at the time

of birth and the kind of employment

marketplaces available in each state of India

appear to be distinct. In this light, more

studies are needed to evaluate Manipur’s

demographic dividend concerning female

labour force participation and fertility. And

also, Manipur’s low economic performance

compared to the other central states of India,

as well as the predominant agriculture-based

employment, has been a source of concern

for this study

The study strictly used the Registrar General

of India’s census data from 1991, 2001, and

2011.

Description of the Study Framework

The commonly acknowledged age range for

reproduction is 15-49. In Indian society, the

reproduction of a child is generally permitted

solely for married women. Every woman is

characterized by her current age, educational

level, religion, health conditions, and activity.

Such self-characterization allows for the

assessment of the appropriate marriage age.

Various characteristics of different women

determine more than just their age at

marriage. The married women, coordinated

with the above characteristics, also determine

the number of children they can bear in their

reproductive life. On the other hand, age at

marriage also determines the number of

children a woman can bear in her reproductive

lifetime and the woman’s work participation

rate. Again, the number of children born and

work participation also affect each other in

determining each other.

The age at marriage is classified into age

groups- below 15, 16-23, and 24 and above

(for the availability of the census data). Again,

the engaged activities were classified into

Main, Marginal, and Non-worker, as defined

by the census. Total, Rural, Urban, and inter

district comparisons were carried out in the

age at marriage section (except 1991). In the

district-wise analysis, no rural and urban

classification was carried out due to the lack

of urban and rural classification in the hill

districts. Due to the unavailability of the data

for age at marriage and activities in the 1991

census, the 1991 analysis is omitted. In the

section on the age and number of children

born, both total and rural/urban will be

discussed. Simple descriptive statistics were

used for the analysis.

Women’s engagement in specific activities

also influences their marriageable age. What

age a woman should marry may be determined

by the activities she has participated in. As the economy improves, women’s educational

attainment increases, and as a result, their

work patterns and ways of generating money

for their families and themselves change. The

age at which a person marries may be

determined by the kind of women they work

with. Women involved in various interests are

more likely to marry later in life. As a result,

it is critical to examine how women’s diverse

activities influence marriage at various ages.

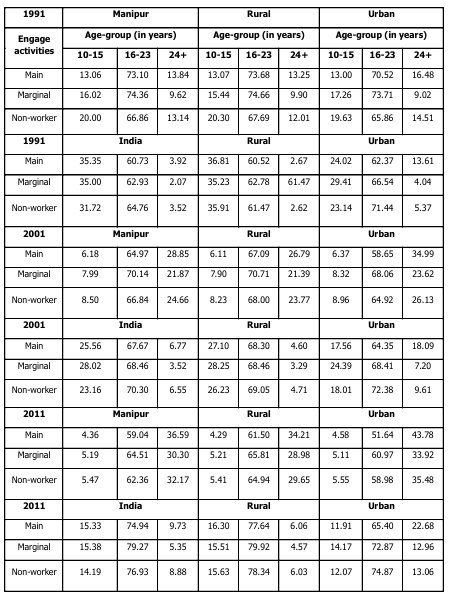

Table No.1. Percentage of Married

Women by their Age at Marriage and

Engage Activities for Manipur, Rural, and

Urban (1991, 2001, and 2011)

Source: Author’s calculation using Census F

3A and F-3B data for 1991 and C-7 data for

2001 and 2011, Manipur.

Table No. 1 illustrates the engagement

activities (Main worker, Marginal worker, and

non-worker) of married women of different

age groups (10-15, 16-23, and 24+) in rural

and urban areas of Manipur and India across

the years 1991, 2001, and 2011. Among the

married women engaged as main workers, it

was observed that Manipur (13.06%) had a

significantly lower proportion of the 10-15

years age group compared to India (35.35%)

in 1991, suggesting that premature marriage

was more prevalent in India than in Manipur.

Among the age group (16-23), the women

engaged as main workers in India had a

consistently higher percentage share,

depicting a larger workforce than in Manipur.

Regarding marginal workers, the percentage

share remained high in both Manipur (5.19%)

and India (15.38%). But those married women

who did not engage (housewives) in any work

activity increased further across all census

years in both Manipur (5.47%) and India

(14.19%). Rural and urban differences,

especially among the main workers, were

generally higher in urban areas than in rural

areas in both Manipur and India, indicating

that more employment opportunities are

available in urban areas.

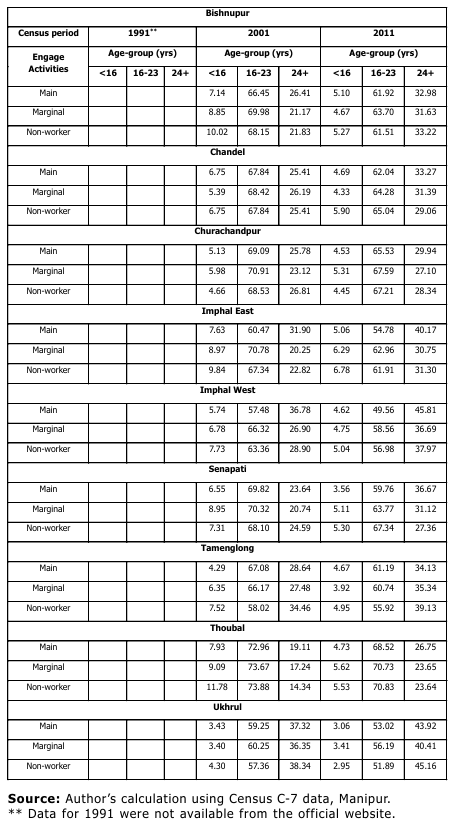

Table-2 shows the age of marriage as

influenced by married women’s activities by

district. The age at marriage for those under

16 and those between 16 and 23 has been

observed to decrease over the census periods

for all activities, while the age at marriage

for those 24 and older has been observed to

grow for all districts. There were substantially

more married women in Senapati among

unemployed women aged 16 to 23 than

among employed women. Again, there were

more married women from Tamenglong,

among the women aged 16 to 23, who were

engaged in their main activity than those

engaged in other occupations. This picture

contradicts previously established criteria,

which stipulate that a more significant

proportion of married women working in

marginal occupations must choose to marry

between the ages of 16 and 23. In the

Tamenglong and Ukhrul districts, the

proportion of women who were unemployed

at the age of 24 or older was much higher than that of women engaged in primary or

secondary jobs. The preceding requirements,

which specify that the majority of married

women in the principal activity must have

decided to marry at the age of 24 or older,

were also in divergence with this signal.

Nonetheless, most women in the remaining

region who engaged in marginal activities

chose to marry between the ages of 16 and

23. Again, a higher proportion of women in

the remaining districts—aside from

Tamenglong and Ukhrul—choose to marry

when they are 24 years old or older, indicating

that women who marry later in life were

actively involved in their main activity

Table No. 2 District-wise Percentage of

Married Women by their Age at Marriage

and Engage Activities (1991, 2001, and

2011).

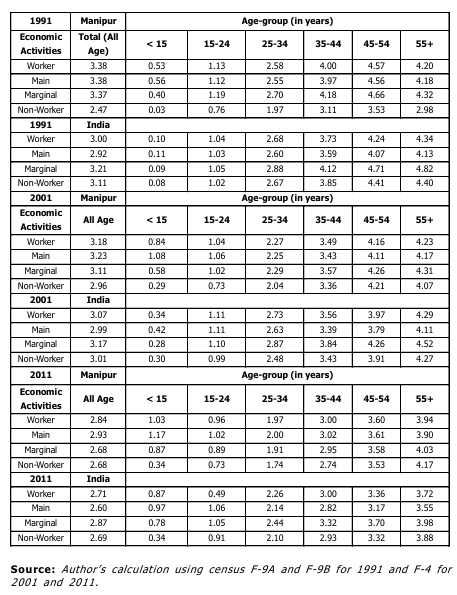

Table 3 shows the number of children born to

women who were actively engaged in their

activities. In both Manipur and India, there is

a general trend of declining fertility rates

across all age groups and economic activity

categories from 1991 to 2011. This suggests

the successful implementation of family

planning programs and increasing access to

reproductive healthcare. In 1991, Manipur

generally had higher fertility rates than India

across all age groups and economic activity

categories. Whereas between 2001 & 2011,

the fertility gap between Manipur and India

narrowed, suggesting that fertility rates in

Manipur declined faster. In terms of work

participation, fertility ra tes were generally

higher among main workers than marginal

workers and non-workers in both Manipur and

India. This could be attributed to various

factors, such as later marriage age and

increased family planning access among non

working women.

Table No. 3. Number of children born by

their age groups and their economic

activities attended by Manipur and India

(1991, 2001, and 2011)

The present paper is intended to highlight the

changes in the fertility rate and female work

participation along with the different age

groups in Manipur, a northeastern state of

India. The finding suggested that the changes

in work participation patterns over time likely

reflect economic development, urbanization,

and changes in social structures. The increase

in the percentage of non-workers, especially

in the younger (10-15) age group, suggests

improvements in education and changes in

social norms regarding child labor and school

attendance. Further, the high percentage of

marginal workers indicates the significance of

informal employment in Manipur and India,

highlighting the need for policies to support

and formalize this sector. Moreover, the

dynamics of economic growth should be a

concern to improve the participation of the

female labour force in harnessing the

demographic dividend. Unfortunately, the

female work participation rate remains

relatively low compared to many developed

countries, indicating that there is still

significant room for improvement in terms of

gender equality and women’s economic

empowerment.

Torres, R. (2015). Executive Summary-World

Employment and Social Outlook: The

changing nature of jobs. World Employ

Soc Outlook, 2015: i-7. https://

doi.org/10.1002/wow3.61

Aydin, H. I., Benghoul, M., & Balacescu, A.

(2019). Women’s Role in Economic

Development a Significant Impact in

the EU Countries? International

Journal of Sustainable Economies

Management (IJSEM), 8(1), 29-38.

10.4018/IJSEM.2019010103

Marone, M. H. (2016). Demographic

dividends, gender equality, and

economic growth: the case of Cabo

Verde. International Monetary Fund

WP, WP/16/169.

Wodon, Q., Onagoruwa, A., Male, C.,

Montenegro, C., Nguyen, H., & De La

Brière, B. (2020). How large is the

gender dividend? Measuring selected

i mpacts and costs of gender

inequality, THE COST OF GENDER

INEQUALITY NOTES SERIES, CIFT,

World Bank Group.

Ali, B., & Dhillon, P. (2022). Cointegration and

Causality between Fertility and

Female Labour Force Participation in

India. Demography India, 51(1), 126

143.

Ahn, N., & Mira, P. (2002). A note on the

changing relationship between fertility

and female employment rates in

developed countries. Journal of

population Economics, 15(4), 667

682. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s001480100078

Majbouri, M. (2019). Twins, family size and

female labour force participation in

Iran. Applied Economics, 51(4), 387

397.

Ukil, P. (2015). Effect of fertility on female

labour force participation in the United

Kingdom. Margin: The Journal of

Applied Economic Research, 9(2),

109–132.

Tumen, S., & Turan, B. (2023). The effect of

fertility on female labor supply in a

l abor market with extensive

i n f o r m a l i t y . E m p i r i c a l

Economics, 65(4), 1855-1894.

Mason, K. O., & Palan, V. T. (1981). Female

employment and fertility in peninsular

Malaysia: The maternal role

i ncompatibility

hypothesis

reconsidered. Demography, 18(4),

549–575.

Fang, H., Eggleston, K. N., Rizzo, J. A., &

Zeckhauser, R. J. (2013). Jobs and

kids: female employment and fertility in China. IZA Journal of Labor &

Development, 2(1), 1–25.

Krishnan, V. (1991). Female labour force

participation and fertility: an

aggregate analysis. Genus, 177–192.

David E. Bloom, David Canning, Günther Fink,

& Jocelyn E. Finlay (2007). Fertility,

Female Labour Force Participation,

and the Demographic Dividend. NBER

WP No. 13583. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s10887-009-9039-9

Luci, A. (2009). Female labour market

participation

and economic

growth. International Journal of

Innovation and Sustainable

Development, 4(2-3), 97–108.

Sarkhel, S., & Mukherjee, A. (2014). Culture,

discrimination and women’s work

force participation: a study on Indian

labor market. Mimeo, Indian

Statistical Institute, Delhi Centre.

Abraham, V. (2013). Missing Labour Force ‘

Or ‘ de-feminization ‘ of Labour Force

in India? Thiruvananthapuram: Centre

for Development Studies. https://

cds.edu/wp-content/uploads/WP452

Kim, J. (2016). Female education and its

impact on fertility. IZA World of Labor.

Altuzarra, A., Gálvez-Gálvez, C., & González

Flores, A. (2019). Economic

Development and Female Labour

Force Participation: The Case of

European

Union

Countries. Sustainability, 11(7), 1962.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071962

Kinoshita, Y., & Guo, F. (2015). What can boost

female labor force participation in

Asia? International Monetary Fund.

IMFWP/15/56

Aydin, H. I., Benghoul, M., & Balacescu, A.

(2019). Women’s Role in Economic

Development a Significant Impact in

the EU Countries? International

Journal of Sustainable Economies

Management (IJSEM), 8(1), 29–38.

10.4018/IJSEM.2019010103

Siegel, C. (2012). Female employment and

fertility: the effects of rising female

wages. CEP Discussion Paper No 1156

July 2012, ISSN 2042-2695.

Fatima, A., & Sultana, H. (2009). Tracing out

the U shape relationship between

female labor force participation rate

and economic development for

Pakistan. International Journal of

Social Economics, 36(1/2), 182–198.

Abdou, D. S., & Shalaby, D. (2019).

Determinants of FLFP and its impact

on economic growth evidence from:

Egypt, Germany, and Pakistan. Sociol

Int J, 3(2), 203-209.

https://

10.15406/sij.2019.03.00176

Alam, I. M., Amin, S., & McCormick, K. (2018).

The effect of religion on women’s

labor force participation rates in

Indonesia. Journal of the Asia Pacific

Economy, 23(1), 31–50. https://

d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 8 0 /

13547860.2017.1351791

Afridi, F., Dinkelman, T., & Mahajan, K. (2018).

Why are fewer married women joining

the workforce in rural India? A

decomposition analysis over two

decades. Journal of Population

Economics, 31, 783–818.

Chaudhary, R., & Verick, S. (2014). Female

labour force participation in India and

beyond. ILO

WPs,

(994867893402676).

Ali, B., & Dhillon, P. (2022). Cointegration and

Causality between Fertility and

Female Labour Force Participation in

India. Demography India, 51(1), 126

143.

Tiwari, C., Goli, S., & Rammohan, A. (2022).

Reproductive burden and its impact on

female labor market outcomes in

India: Evidence from longitudinal

analyses. Population Research and

Policy Review, 41(6), 2493–2529. Mahapatro, S. R. (2013). Changing trends in

female labour force participation in

India: An age-period-cohort

analysis. Indian Journal of Human

Development, 7(1), 83-107.

Mawkhlieng, D. R., & Algur, K. (2021).

Workforce participation in north-east

India. IASSI-Quarterly, 40(4), 782

794.

Lahoti, R., & Swaminathan, H. (2013).

Economic development and female

labor force participation in India. IIM

Bangalore Research Paper, (414).

Sarkar, S., Sahoo, S., & Klasen, S. (2019).

Employment transitions of women in

India: A panel analysis. World

Development, 115, 291–309.

Das, M. B., & Zumbyte, I. (2017). The

motherhood penalty and female

employment in urban India. World

Bank Group, Social, Urban, Rural, and

Resilience Global Practice Group

Policy Research WP 8004.

Sorsa, P., Mares, J., Didier, M., Guimaraes, C.,

Rabate, M., Tang, G., & Tuske, A.

(2015). Determinants of the low

female labour force participation in

India. OECD Economics Department

WPs No. 1207.

Das, I. (2013). Status of women: North

Eastern region of India versus

India. International journal of

scientific

and

research

publications, 3(1), 1–8.

Kaur, P. (2016). Factors Affecting Female

Labor Force Participation in North East

India. International Journal of

Humanities and Social Science

Studies, 3(2), 159–166.

Srivastava, N., & Srivastava, R. (2010).

Women, work, and employment

outcomes in rural India. Economic and

political weekly, 49-63.

Pegu, A. (2015). Female workforce

participation in north-eastern region:

An overview. International Journal of

Humanities & Social Science Studies

(IJHSSS), 1(4), 154–160.