Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

EFFICACY OF SINGLE SESSION WORKSHOP USING PRINCIPLES OF

ACT IN PROMOTING PSYCHOLOGICAL HELP-SEEKING IN HIGHER

EDUCATION SETTINGS: A PRELIMINARY SURVEY

Vikas Kumar1 & Shuvabrata Poddar2

1PhD Research Scholar, Department of Applied Psychology, Kazi Nazrul University, Asansol, and

Assistant Professor, Amity Institute of Clinical Psychology, Amity University, Patna. 2Assistant

Professor, Department of Applied Psychology, Kazi Nazrul University, Asansol.

Correspondence: Vikas Kumar, e-mail: ku.vikasbhu@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Background: The reluctance of higher education students to seek psychological care, despite

rising mental health concerns, highlights the importance of brief and effective interventions.

This study investigates the efficacy of a single-session Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

(ACT) intervention in improving psychological help-seeking behaviour among college students.

Methods & Materials: A sample of 30 students took part in a pre-post experimental design,

with help-seeking attitudes measured using the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional

Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPH-SF). Results: The findings demonstrated a statistically

significant increase in attitudes toward help-seeking following intervention, showing the potential

of ACT as a brief, effective method. Conclusion: These findings have significance for campus

mental health outreach and the incorporation of ACT into prevention initiatives.

Keywords: Single-Session Intervention, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Help-Seeking

Behaviour, Higher Education, Students’ Mental Health.

INTRODUCTION

Mental health concerns among higher

education students are on the rise, with a

significant portion of students experiencing

stress, anxiety, depression, and adjustment

difficulties (Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010). Despite

the increasing prevalence of psychological

issues, a large number of students do not

actively seek professional psychological help.

Barriers such as stigma, lack of awareness,

cultural misconceptions, and negative

attitudes toward counselling contribute to this

help-seeking gap (Rickwood et al., 2007;

Eisenberg, Speer, & Hunt, 2012).

In recent years, researchers have worked to

understand and remove these barriers, with

a focus on designing brief, accessible, and

effective psychological interventions that

encourage people to seek mental health help.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

is one strategy that has produced encouraging

outcomes. Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson (1999)

developed ACT, a third-wave behavioural

intervention that stresses psychological

flexibility by encouraging people to accept their

internal experiences while doing meaningful,

value-driven behaviours. ACT consists of six key processes: cognitive defusion,

acceptance, touch with the present moment,

self-observation, values, and committed

action (Hayes et al., 2006). Unlike traditional

cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), which

focuses on changing the content of thoughts,

ACT promotes a new relationship with

thoughts and feelings—allowing individuals to

engage in valued behaviours even in the

presence of discomfort. This makes it

particularly suitable for individuals

experiencing internal conflicts, avoidance, or

fear around psychological support and stigma.

Research suggests that ACT can effectively

treat depression, anxiety, and stress (Powers

et al., 2009; Öst, 2014). Furthermore, new

research has looked into the impact of brief

ACT interventions, including single-session

formats, on particular objectives like stress

reduction, self-stigma reduction, and

psychological flexibility (Levin et al., 2017).

However, its use in directly influencing help

seeking behaviour among university students

remains relatively unexplored, particularly in

the Indian setting. According to research,

young adults, particularly those in college,

frequently struggle to recognize their mental

health issues and seek prompt professional

help (Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010).

Attitudes toward psychological help-seeking

play a pivotal role in this behaviour, where

negative beliefs or internalized stigma reduce

the likelihood of accessing available services

(Corrigan, 2004). In a meta-analytic review,

Vogel, Wester, and Larson (2007) found that

self-stigma was negatively associated with

help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Such

internal barriers are prevalent among Indian

students as well, where cultural expectations

and lack of psychological awareness further

complicate help-seeking efforts (Sharma &

Reddy, 2015). Intervention strategies aimed

at improving help-seeking behaviours have

traditionally involved awareness programs,

psychoeducation, or stigma reduction

campaigns (Yorgason, Linville, & Zitzman,

2008). However, these approaches often

require multiple sessions or institutional

commitment. Hence, brief interventions that

can be implemented in a single session and

still demonstrate efficacy are especially

valuable.

The effectiveness of single-session

interventions (SSIs) in both clinical and non

clinical populations has drawn attention due

to their focused and efficient effects (Schleider

& Weisz, 2017). According to Levin et al.

(2014) and Bricker et al. (2013), ACT-based

SSIs have been shown to be successful in

l owering experiential avoidance and

enhancing psychological flexibility and self

compassion. These are important processes

to overcome internal resistance to asking for

help. Levin et al. (2017) showed that even a

one-hour ACT-based intervention significantly

reduced stigma around mental health and

increased college students’ receptivity to

therapy. By focusing on acceptance and values

clarification, ACT helps people rewrite their

inner stories and create space for self-care

related actions, such as asking for help.

Studies explicitly examining ACT’s effect on

help-seeking attitudes are still scarce despite

these encouraging results, especially in

academic contexts with limited resources or

high levels of stigma in developing nations.

In order to fill this gap, this study investigates

i f ACT, even for just one session, can

i nfluence students’ attitudes toward

requesting assistance.

The underutilization of psychological services

by students despite increasing mental health

concerns presents a serious challenge for

educational institutions and mental health

professionals. According to Eisenberg et al.

(2012), over 60% of college students

experiencing mental health issues do not seek

any form of professional support. In India, the

challenge is compounded by cultural norms,

stigma, and a lack of mental health infrastructure in academic settings. Many

students hesitate to seek help due to

internalized shame, fear of judgment, or

belief that their problems should be managed

independently (Sahoo & Khess, 2010). Given

these barriers, there is an urgent need to test

and implement evidence-based, low-cost, and

scalable interventions that can be delivered

within the campus environment. ACT, with its

emphasis on value-driven behaviour and

acceptance, is particularly well-suited to

target psychological inflexibility—one of the

key predictors of avoidance and inaction in

mental health seeking (Hayes et al., 2006).

Furthermore, because students may be unable

to attend therapy because of time constraints,

conflicting academic priorities, or early

resistance to multi-session treatment, single

session models are well-suited for the higher

education setting. By reducing psychological

resistance and encouraging a more positive

attitude toward therapy, a successful one

session ACT intervention may serve as a

“gateway experience” into professional help

seeking behaviour. Therefore, by examining

the early efficacy of a single-session ACT

based intervention in altering students’

attitudes toward seeking help, the current

study seeks to close a substantial research

and practice gap. Additionally, keep in mind

that single-session models work best in higher

education settings when students may initially

be resistant to multi-session therapy or have

time constraints or conflicting academic

obligations. Because it lowers psychological

resistance and fosters more adaptable

attitudes toward therapy, a successful one

session ACT intervention could be used as a

first step toward getting help. In light of this,

this study closes a significant research and

practice gap by evaluating the initial efficacy

of a one-session ACT-based intervention in

altering students’ attitudes toward seeking

help.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

The study was conducted with a sample of 30

higher education students (n = 30) enrolled

in undergraduate and postgraduate courses

across various disciplines at universities in

India. Participants were selected using

purposive sampling. The inclusion criteria

required participants to be between 18 and

25 years old and to have not received any

form of psychological intervention in the last

six months. Those with a diagnosed

psychiatric condition were excluded.

Design

A pre-post single-group experimental design

was used to evaluate the effectiveness of a

Single-Session Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy (ACT) intervention on psychological

help-seeking behaviour.

TOOLS USED

1. Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II

(AAQ-II): The AAQ-II is a 7-item self

report instrument developed by Bond et

al. (2011) to assess psychological

inflexibility or experiential avoidance. Each

item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale

ranging from 1 (“never true”) to 7

(“always true”). Higher scores indicate

greater psychological inflexibility. The

AAQ-II has demonstrated good internal

consistency (á = .84) and test-retest

reliability (r = .81) (Bond et al., 2011).

2. Self-Stigma of Seeking Help Scale (SSOSH): The SSOSH is a 10-item scale designed by Vogel et al. (2006) to assess the degree to which individuals believe they would be devalued if they sought psychological help. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Higher scores suggest higher levels of self stigma. The scale has shown adequate internal consistency (á = .86).

3. Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale – Short Form (ATSPPH-SF): This is a 10-item scale developed by Fischer and Farina (1995) to measure general attitudes toward seeking psychological help. It uses a 4 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“disagree”) to 3 (“agree”). Higher scores represent more positive attitudes. The ATSPPH-SF has demonstrated acceptable internal reliability (á = .77) and validity across different populations.

2. Self-Stigma of Seeking Help Scale (SSOSH): The SSOSH is a 10-item scale designed by Vogel et al. (2006) to assess the degree to which individuals believe they would be devalued if they sought psychological help. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Higher scores suggest higher levels of self stigma. The scale has shown adequate internal consistency (á = .86).

3. Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale – Short Form (ATSPPH-SF): This is a 10-item scale developed by Fischer and Farina (1995) to measure general attitudes toward seeking psychological help. It uses a 4 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“disagree”) to 3 (“agree”). Higher scores represent more positive attitudes. The ATSPPH-SF has demonstrated acceptable internal reliability (á = .77) and validity across different populations.

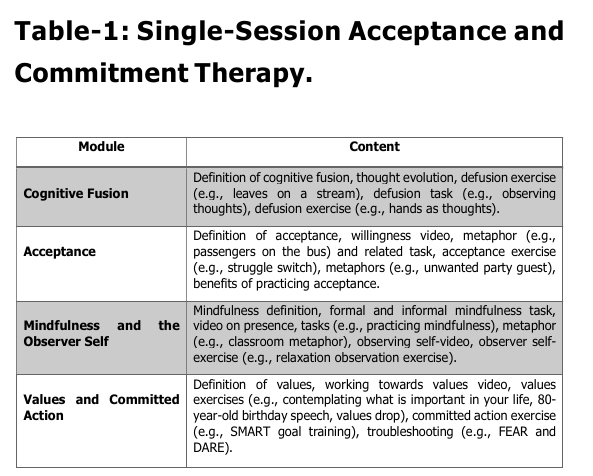

INTERVENTION

Single-Session Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy (SSACT) based intervention was

applied with students as a therapeutic

module, adapted from Thomas, K. (2021) ‘s

A One-Session, Brief Acceptance and

Commitment Therapy Workshop. The module

has been adopted for the current study.

However, few therapeutic techniques had been

tailored to meet their need, and a better

understanding of the students was needed to

meet the treatment efficacy. This adapted and

culturally relevant therapeutic module has

been approved by the university ethics

committee. The details of the Single-Session

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Workshop are presented in Table 1.

PROCEDURE

Participants were given informed permission

and instructed on the study’s aims. Three

standardized self-report measures were used

to conduct the baseline assessment: the

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II

(AAQ-II), the Self-Stigma of Seeking Help

Scale (SSOSH), and the Attitudes Toward

Seeking Professional Psychological Help

Short Form. Following that, participants

received a 90-minute structured single

session ACT intervention that emphasized

cognitive defusion, acceptance, value

clarification, and committed action. A week

later, post-intervention assessments utilizing

the same three measures were done.

RESULTS

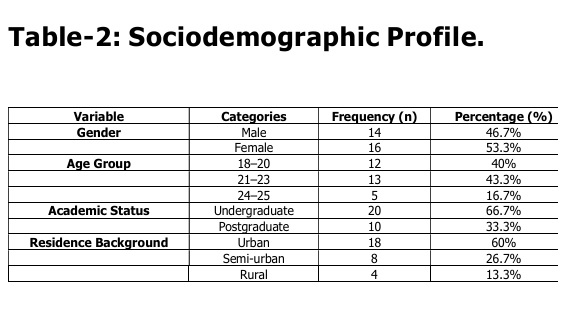

Table-2: explained sample included 16

females (53.3%) and 14 males (46.7%), with

a mean age of 21.4 years (SD = 2.01). The

majority of participants were from urban

backgrounds (60%), while the rest were from

semi-urban (26.7%) and rural (13.3%) areas.

Academic levels included undergraduate

(66.7%) and postgraduate (33.3%) students.

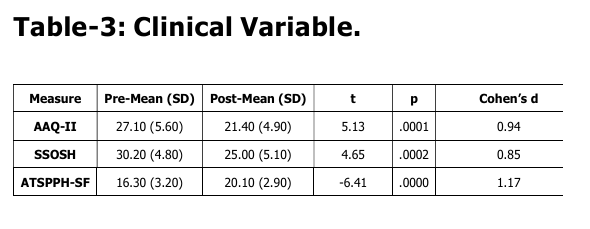

The results revealed statistically significant

differences in the pre-and post-intervention

scores for all three measures:

1. Psychological Inflexibility (AAQ-II):

Scores significantly decreased post intervention (t(29) = 5.13, p < .001), i ndicating improved psychological flexibility. A large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.94) suggests the ACT session had a substantial impact.

Scores significantly decreased post intervention (t(29) = 5.13, p < .001), i ndicating improved psychological flexibility. A large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.94) suggests the ACT session had a substantial impact.

2. Self-Stigma (SSOSH):

Participants showed a significant reduction in self stigma (t(29) = 4.65, p < .001). The effect size (d = 0.85) indicates a substantial change in perception toward stigma about help-seeking.

Participants showed a significant reduction in self stigma (t(29) = 4.65, p < .001). The effect size (d = 0.85) indicates a substantial change in perception toward stigma about help-seeking.

3. Attitudes Toward Help-Seeking

(ATSPPH-SF):

Scores significantly increased (t(29) = -6.41, p < .001), reflecting improved attitudes toward seeking professional help. The very large effect size (d = 1.17) highlights the intervention’s robust impact.

Scores significantly increased (t(29) = -6.41, p < .001), reflecting improved attitudes toward seeking professional help. The very large effect size (d = 1.17) highlights the intervention’s robust impact.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to evaluate the

effectiveness of a single-session Acceptance

and Commitment Therapy (ACT) intervention

in increasing psychological help-seeking

behaviour among higher education students.

This work was motivated by growing concerns

about poor mental health care utilization rates

among college students despite rising

psychological discomfort (Eisenberg et al.,

2012). The study’s findings give early

evidence that even a brief ACT session can

drastically change students’ attitudes toward

obtaining professional psychological

treatment.

The findings revealed a statistically significant

change in post-intervention ratings on the

Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional

Psychological Help – Short Form (ATSPPH-SF),

i ndicating more positive help-seeking

attitudes following the ACT session. The pre

to post-intervention difference was associated

with a substantial effect size (Cohen’s d =

1.14), indicating both statistical and practical

importance. These findings are consistent

with previous research demonstrating the

effectiveness of ACT in reducing psychological

avoidance and boosting readiness to seek help

(Levin et al., 2016; Roush et al., 2018). This

study expands on existing literature by using

ACT in a single-session format, which has

previously been proven to be helpful in

j uvenile populations for a variety of

psychological disorders (Schleider & Weisz,

2017). The current findings align with the

notion that psychological flexibility—ACT’s

central mechanism—may play a critical role

in changing maladaptive attitudes toward

professional help-seeking.

Psychological Flexibility and Help-Seeking

Behavior

One of the fundamental concepts of ACT is to

improve psychological flexibility, which refers

to the ability to be open to new experiences,

stay present, and act on personal ideals

(Hayes et al., 2006). In the context of

psychological help-seeking, this flexibility

enables people to face the unpleasantness

that comes with seeking help (e.g., stigma,

self-doubt) and commit to behaviours that

promote personal well-being. Previous studies

have demonstrated that more psychological

flexibility is associated with more positive

attitudes about mental health care (Masuda

et al., 2012). In the present study, methods

l ike values clarification, defusion, and

mindfulness were probably crucial in fostering

acceptance of mental health needs and

combating internalized stigma. Through the

use of ACT metaphors, such as “Passengers

on the Bus” or “Tug-of-War with a Monster,”

students who might ordinarily view asking for help as a sign of weakness may be able to

shift their viewpoint and break free from these

damaging narratives. A mental shift brought

about by these hands-on activities can make

people more receptive to receiving support

services.

Role of Stigma in Help-Seeking Barriers

Stigma continues to be one of the most

significant barriers to student mental health

service utilization (Corrigan, 2004). ACT

addresses stigma by increasing acceptance of

stigmatizing beliefs and diminishing their

behavioural influence rather than aiming to

erase them. This method differs from

cognitive-behavioural models in that it focuses

on the process of defusion rather than the

content of stigmatizing beliefs (Hayes et al.,

1999). The current study’s excellent findings

indicate that even in a brief intervention

format, ACT can successfully reduce the

functional impact of stigma on help-seeking

behaviour. By reframing mental health support

as a values-based action rather than a sign

of personal inadequacy, students may become

more inclined to seek help, particularly when

guided by the principle of living a meaningful

life.

Effectiveness of Single-Session Interventions

Utilizing a single-session approach, which is

scalable and resource-efficient, was one

noteworthy feature of the study. Although

multi-session therapies have historically been

the standard in clinical psychology, new

studies have shown the benefits of brief and

ultra-brief interventions, especially for

populations that are reluctant to commit to

longer-term therapy or have time constraints

(Schleider & Weisz, 2016). Key therapeutic

components were crammed into a 90-minute

ACT session, which was intended to be

intense and highly experiential in the current

study. Although brief, the intervention resulted

in a notable change in attitudes, indicating

that content quality and relevance may be

more important than duration, especially in

preventive or attitudinal treatments. This

finding is crucial in higher education settings

since counselling clinics are frequently

underfunded and overburdened (Gallagher,

2014). Implementing brief, ACT-informed

workshops could be a viable first-line method

to enhance psychological openness among

students, thereby increasing the adoption of

additional therapies as needed.

Implications for Practice

The present findings carry several practical

implications:

1. The intervention is cost-effective and needs minimal resources, making it suitable for widespread implementation across academic institutions.

2. ACT can help improve clinical therapy and mental wellness. As a result, the intervention concentrating on attitudes has the potential to improve the early detection and intervention processes.

3. ACT is adjustable and may be adjusted to different groups based on cultural and gender factors, making it incredibly versatile.

4. Non-clinical practitioners, such as academic counsellors or peer mentors, can effectively apply ACT-based therapies with proper training and supervision, expanding their reach.

5. Digitization aligns well with the ACT paradigm. Previous research (Levin et al., 2014) has demonstrated that online delivery of ACT modules improves availability for students who are unwilling to attend face-to-face sessions.

1. The intervention is cost-effective and needs minimal resources, making it suitable for widespread implementation across academic institutions.

2. ACT can help improve clinical therapy and mental wellness. As a result, the intervention concentrating on attitudes has the potential to improve the early detection and intervention processes.

3. ACT is adjustable and may be adjusted to different groups based on cultural and gender factors, making it incredibly versatile.

4. Non-clinical practitioners, such as academic counsellors or peer mentors, can effectively apply ACT-based therapies with proper training and supervision, expanding their reach.

5. Digitization aligns well with the ACT paradigm. Previous research (Levin et al., 2014) has demonstrated that online delivery of ACT modules improves availability for students who are unwilling to attend face-to-face sessions.

Limitations

While the study offers valuable preliminary

i nsights, several limitations must be

acknowledged:

1. With only 30 participants, the study’s findings cannot be generalized. Larger sample sizes would provide better statistical power.

2. The absence of a control or comparison group prevents causal inference. A randomized controlled design would i mprove internal validity in future research.

3. Attitudes were assessed shortly after the intervention. Longitudinal research would be required to assess whether improved attitudes may be converted into actual help-seeking behaviour, as well as whether such an effect is long-lasting.

4. The use of self-report measures, such as the ATSPPH-SF, may result in social desirability or response bias. Accepting behavioural evidence of help-seeking or follow-up usage data from the university counselling service may provide methodological enhancements in future research.

1. With only 30 participants, the study’s findings cannot be generalized. Larger sample sizes would provide better statistical power.

2. The absence of a control or comparison group prevents causal inference. A randomized controlled design would i mprove internal validity in future research.

3. Attitudes were assessed shortly after the intervention. Longitudinal research would be required to assess whether improved attitudes may be converted into actual help-seeking behaviour, as well as whether such an effect is long-lasting.

4. The use of self-report measures, such as the ATSPPH-SF, may result in social desirability or response bias. Accepting behavioural evidence of help-seeking or follow-up usage data from the university counselling service may provide methodological enhancements in future research.

Recommendations for Future Research

1. Comparing ACT against control groups or

other brief therapies, such as

psychoeducation or motivational

interviewing, can provide more conclusive

evidence of success.

2. Tracking help-seeking behaviours for 3 to 6 months after intervention can assess the long-term impact of attitudinal change.

3. To further understand how ACT affects help-seeking behaviour, it’s important to investigate if psychological flexibility or stigma plays a role.

4. Adapting ACT to varied student demographics, particularly those with collectivistic ideals, can increase its acceptability and effectiveness.

5. Collaborating with student mental health groups or peer counsellors can increase reach and engagement, especially for students who are unsure about formal psychological services.

2. Tracking help-seeking behaviours for 3 to 6 months after intervention can assess the long-term impact of attitudinal change.

3. To further understand how ACT affects help-seeking behaviour, it’s important to investigate if psychological flexibility or stigma plays a role.

4. Adapting ACT to varied student demographics, particularly those with collectivistic ideals, can increase its acceptability and effectiveness.

5. Collaborating with student mental health groups or peer counsellors can increase reach and engagement, especially for students who are unsure about formal psychological services.

CONCLUSION

The current study provides hopeful evidence

t hat one session of Acceptance and

Commitment Therapy (ACT) can positively

i nfluence higher education students’

psychological help-seeking attitudes. Though

the intervention was brief, the impact on

students’ willingness to seek professional

psychiatric care was significant and

important. Given the critical need to address

mental health issues in higher education

settings, time-limited, low-threshold, and

scalable therapies like ACT have enormous

potential. The ACT process works by

i ncreasing psychological flexibility,

normalizing experiencing discomfort, and

beginning action that aligns with personal

beliefs. As a result, it could play an important

role in lowering obstacles to mental health

treatment. Although further research is

required to analyze and expand on these

preliminary findings, the therapeutic

implications are promising and practical.

REFERENCES

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A.,

Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt,

H. K., … & Zettle, R. D. (2011).

Preliminary psychometric properties of

t he Acceptance and Action

Questionnaire–II: A revised measure

of psychological inflexibility and

experiential avoidance. Behavior

Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

Bricker, J. B., Wyszynski, C. M., Comstock, B.

A., & Heffner, J. L. (2013). Pilot

randomized controlled trial of web

based acceptance and commitment

therapy for smoking cessation.

Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(10),

1756–1764. https://doi.org/10.1093/ ntr/ntt035

Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes

with mental health care. American

Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. https:/

/doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes

with mental health care. American

Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. https:/

/doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., & Speer, N. (2012).

Help seeking for mental health on

college campuses: Review of

evidence and next steps for research

and practice. Harvard Review of

Psychiatry, 20(4), 222–232. https://

d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 3 1 0 9 /

10673229.2012.712839

Eisenberg, D., Speer, N., & Hunt, J. B. (2012).

Attitudes and beliefs about treatment

among college students with

untreated mental health problems.

Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 711–713.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 1 76 /

appi.ps.201100250

Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes

t oward seeking professional

psychological help: A shortened form

and considerations for research.

Journal of College Student

Development, 36(4), 368–373.

Gallagher, R. P. (2014). National survey of

college counseling centers 2014.

American College Counseling

Association.

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H.

(2010). Perceived barriers and

facilitators to mental health help

seeking in young people: A systematic

review. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 113.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X

10-113

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W.,

Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006).

Acceptance and commitment therapy:

Model, processes and outcomes.

Behaviour Research and Therapy,

44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.brat.2005.06.006

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W.,

Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006).

Acceptance and commitment therapy:

Model, processes and outcomes.

Behaviour Research and Therapy,

44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.brat.2005.06.006

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G.

(1999). Acceptance and commitment

therapy: An experiential approach to

behavior change. Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G.

(1999). Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy: An experiential approach to

behavior change. Guilford Press.

Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health

problems and help-seeking behavior

among college students. Journal of

Adolescent Health, 46(1), 3–10.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 16 /

j.jadohealth.2009.08.008

Levin, M. E., Haeger, J., Pierce, B. G., & Cruz,

R. A. (2017). Evaluating an

acceptance and commitment therapy

workshop for college students: A

randomized controlled trial. Cognitive

Behaviour Therapy, 46(1), 1–20.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 80 /

16506073.2016.1214293

Levin, M. E., Krafft, J., Pistorello, J., Seeley,

J. R., & Hayes, S. C. (2017). Evaluating

an acceptance and commitment

t herapy workshop for college

students: A randomized controlled

trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy,

46(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/

16506073.2016.1214293

Levin, M. E., Pistorello, J., Seeley, J. R., &

Hayes, S. C. (2014). Testing the

effects of a web-based acceptance

and commitment therapy intervention

for mental health stigma. Behavior Modification, 38(6), 791–813. https:/

/doi.org/10.1177/0145445514524880

Masuda, A., Anderson, P. L., & Sheehan, S. T.

(2009). Cognitive defusion and self

relevant negative thoughts: Examining

the impact of a ninety year old

technique. Behaviour Research and

Therapy, 47(7), 565–573. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.003

Öst, L. G. (2014). The efficacy of Acceptance

and Commitment Therapy: An updated

systematic review and meta-analysis.

Behaviour Research and Therapy, 61,

105–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.brat.2014.07.018

Powers, M. B., Zum Vörde Sive Vörding, M.

B., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2009).

Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy: A meta-analytic review.

Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics,

78(2), 73–80. https://doi.org/

10.1159/000190790

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., &

Ciarrochi, J. (2007). Young people’s

help-seeking for mental health

problems. Australian e-Journal for the

Advancement of Mental Health, 4(3),

218–251.

Roush, S. E., Brown, S. L., & Morrow, S. L.

(2018).

College

students’

psychological help-seeking intentions

and behavior: An application of the

Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal

of American College Health, 66(5),

421–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/

07448481.2018.1440570

Sahoo, S., & Khess, C. R. J. (2010).

Understanding stigma and its impact

on mental health. Mental Health: An

Indian Perspective, 217–225.

Schleider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2016).

Reducing risk for anxiety and

depression in adolescents: Effects of

a single-session intervention teaching

that personality can change. Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 87, 170–181.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 16 /

j.brat.2016.09.011

Schleider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2017). Little

treatments, promising effects? Meta

analysis

of

single-session

interventions for youth psychiatric

problems. Journal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 56(2), 107–115. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.11.007

Schleider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2017). Little

treatments, promising effects? Meta

analysis

of

single-session

interventions for youth psychiatric

problems. Journal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 56(2), 107–115.

Sharma, M., & Reddy, S. (2015). Barriers to

mental health service utilization

among students in India: A systematic

review. International Journal of

Culture and Mental Health, 8(2), 120

136. https://doi.org/10.1080/

17542863.2014.892531

Twohig, M. P., & Levin, M. E. (2017).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

as a treatment for anxiety and

depression: A review. Psychiatric

Clinics of North America, 40(4), 751

770. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.psc.2017.08.009

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Haake, S. (2006).

Measuring the self-stigma associated

with seeking psychological help.

Journal of Counseling Psychology,

53(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/

10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325

Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., & Larson, L. M.

(2007). Avoidance of counseling:

Psychological factors that inhibit

seeking help. Journal of Counseling &

Development, 85(4), 410–422. https:/

/ d o i . o r g / 1 0. 1 002/j. 1 5 56

6678.2007.tb00609.x Yorgason, J. B., Linville, D., & Zitzman, B.

(2008). Mental health help-seeking

intentions among college students:

Assessing the role of perceived norms

and stigma. Journal of College Student

Psychotherapy, 22(4), 306–320.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 80 /

87568220802397441

Conflict of interest: None

Role of funding source: None