This case study explores the complex interplay between parental pressure, academic stress, and

depression The study aims to assess psycho-social factors and evaluate the effectiveness of

psycho-social interventions in managing depression. This single-subject case study assesses the

effectiveness of the bio-psycho-social model in understanding depression and its treatment through

psychiatric social work intervention. Employing pre- and post-intervention baseline assessments,

the study utilizes various tools including the Family Assessment Device (FAD), Beck Depression

Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Scale, Self-Esteem Scale, Multi-Dimensional Perceived Social Support

Scale, Perceived Stress Scale, a family questionnaire, Internet Addiction Scale, Brief Sex Addiction

Screening Instrument (PATHOS), and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). The

case was referred for assessment and intervention. The intervention comprised CognitiveBehavioural Therapy (CBT)and mindfulness-based intervention. Additionally, the family intervention

was provided to address parental academic pressure towards the patient and educate the family

members about the illness. Following Psychosocial intervention, there were significant changes

in pre- and post-intervention scores across various domains, stress, depression, anxiety, selfesteem, internet addiction, pornography addiction, and mindfulness. The study underscores the

effectiveness of psycho-social interventions in addressing depression influenced by academic

and parental pressures.

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage

characterized by extensive changes and

heightened vulnerability to psychological

disorders such as anxiety and

depression(Sawyer, Azzopardi,

Wickremarathne, Patton, 2018 & McCanceKatz, 2018). This vulnerability is exacerbated

by academic pressures and high-stress family

environments, which contribute significantly

to the risk of mental health issues, including

suicidal ideation. Parenting styles marked by

inconsistency, harsh discipline, and emotional

detachment further complicate adolescents’

emotional and social development, negatively

affecting their academic performance and

social relationships. Despite the availability of

treatments like cognitive-behavioural therapy

(CBT) (Hofmannet, 2012). and mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Goldberg et

al.,2018 & Strauss et al.,2014) which have

been proven effective in managing symptoms

of depression and anxiety, there is a notable

deficiency in interventions specifically tailored

to address the unique challenges faced by

adolescents dealing with academic and

familial stress The intervention intends to

reduce stress and enhance overall

psychological well-being by addressing the

specific psychosocial factors that impact this

age group. This approach is crucial for

developing more targeted and effective mental

health support for adolescents, thereby

improving their long-term outcomes in both

academic and personal spheres. Family

interventions can play a crucial role in treating

adolescent depression by addressing

interpersonal dynamics that may contribute

to the condition(Diamond & Josephson, 2005).

Effective family psychoeducation, focusing on

understanding depression through a medical

model, educating on patient-specific issues,

and teaching about stress vulnerability and

coping strategies, has shown promising

results. Such interventions not only reduce

depressive symptoms in the short term but

also enhance social functioning and improve

relationships with parents and peers,

contributing to long-term mental health

benefits for adolescents. The effectiveness of

existing interventions varies, and there

remains a significant gap in targeted

psychosocial strategies that address the

specific needs of adolescents experiencing

academic and familial stress. This

underscores the importance of a tailored

approach that considers the psychosocial

factors influencing adolescent mental health.

Therefore, this study seeks to evaluate the

impact of a comprehensive psychosocial

intervention designed to alleviate stress and

improve the psychological well-being of the

client.

This study employs a single case study design

to assess the effectiveness of a psychosocial

intervention based on the biopsychosocial

approach for individuals with moderate

symptoms of depression and anxiety. Pre and

post-intervention baseline data are compared

to evaluate changes in the client’s condition.

The present case was purposefully selected

from the Outpatient Department of tertiary

care institute in Delhi. Before the

commencement of the study, informed

consent was obtained from the client’s father,

mother, sister, and teachers, as well as from

the client himself. Participants were assured

about the confidentiality of their information

and were provided with detailed information

about the nature and purpose of the study.

Baseline data were collected before the

commencement of the psycho-social

intervention. Using a standardised scale.

Family Assessment (FAD)(Epstein,Baldwin, &

Bishop, 1983)Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

(Beck et al.,1961), Beck Anxiety Scale(Beck,

Steer, 1990), Self-Esteem Scale(Rosenberg ,

1965). Multi-Dimensional Perceived Social

Support Scale(Zimet,Dahlem, Zimet & Farle,

1988). Perceived Stress Scale(Cohen,

Kamarck & Mermelstein, 1983). Internet

Addiction Scale(Young, 1998).Brief sex

addiction screening instrument (PATHOS)

(Carnes et al.,2012)and the Five Facet

Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer,

2006) were administered. Ethical guidelines

and principles were followed throughout the

study to ensure the rights, dignity, and

confidentiality of the participants.

Mr. X an 18-year-old single male, currently

pursuing his Bachelor’s degree from IGNOU

while simultaneously preparing for civil

services exams, was brought to Tertiary care

centre by his father. He presented with chief

complaints of anxiousness, low mood, lack of interest in work, chest pain, restlessness,

overthinking, stomach pain, and

preoccupation with health concerns.Mr. X hails

from a middle socio-economic status rural

background, with both parents engaged in

farming and cattle rearing. His parents held

high expectations for him to succeed in the

civil services exams, leading to his enrollment

in coaching classes in Delhi. Despite facing

difficulties in keeping up with his studies and

enduring a daily five-hour commute to and

from the coaching centre, Mr X did not

communicate his struggles to his parents and

continued attending classes regularly.

Described as introverted, Mr.X refrained from

expressing his problems to his family and

preferred solitude in his room. During study

breaks, he began watching pornography

videos on his mobile phone, eventually

developing an addiction. This behavior change

was noted by his family, along with complaints

of headaches, stomach pains, and chest pains.

Concerned about his well-being, Mr. X’s father

sought professional help. Upon assessment,

Mr. X was diagnosed with moderate

depression, and treatment was initiated

alongside a referral for psychosocial

intervention. In response to his condition, a

comprehensive treatment plan was developed,

which included both pharmacological and

psychosocial interventions. Therapy sessions

were initially scheduled on a monthly basis

for one year to establish a foundation for

treatment and address his immediate needs.

Following this period, sessions were planned

bi-monthly to continue addressing his mental

health concerns and support his ongoing

recovery. The therapeutic approach help the

client to manage his depression, cope with

stress more effectively, and address his

pornography addiction while gradually

improving his overall well-being and quality

of life.

Mr. X exhibits symptoms of depression and

anxiety, including low mood, somatic

complaints, poor sleep, and decreased

appetite. These symptoms suggest

dysregulation of neurotransmitters and the

autonomic nervous system, potentially

contributing to his mental health struggles.

Mr.X’s introverted personality, poor coping and

problem-solving skills, and low self-esteem

further exacerbate his mental health

challenges. These psychological factors may

hinder his ability to effectively communicate

and manage stressors, leading to maladaptive

behaviours such as excessive mobile use and

addiction. Family dynamics play a significant

role in Mr. X’s mental health. The pressure

from his parents to excel academically,

combined with a dominant father and

submissive mother, contributes to

communication difficulties and feelings of

inadequacy.Additionally, maladaptive parentchild communication and a high degree of

aversiveness in the family environment further

impact Mr. X’s emotional well-being. Mr. X’s

mental health struggles arise from a complex

interplay of biological, psychological, and

social factors. Biological factors such as

neurotransmitter dysregulation contribute to

his symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Psychological factors, including introversion,

poor coping skills, and low self-esteem,

exacerbate his distress and hinder his ability

to manage stressors effectively. Social

factors, particularly parental pressure and

communication difficulties within the family,

create a stressful environment that

perpetuates Mr X’s mental health challenges.

A total of 24 individual and 4 family therapy

sessions were conducted as part of the

intervention. Rapport was established with the

client and their family, and informed consent

was obtained before the commencement of therapy. Clear goals were set collaboratively

between the therapist and the client, and

detailed information about the therapeutic

process, including the timing and duration of

sessions, was provided. This ensured that the

client and their family were fully informed and

engaged in the therapy process, promoting a

supportive and collaborative therapeutic

relationship.In the cognitive-behavioural

therapy (CBT) sessions conducted for Mr. X

the ABC model was employed to address his

depression. The ABC model framework was

used in CBT to help the client understand the

connection between their thoughts, emotions,

and behaviours. During the CBT sessions, the

focus was on modifying underlying schemas

or core beliefs that were contributing to Mr.

X’s depression. By identifying and challenging

maladaptive schemas related to self-worth,

achievement, and coping, Mr. X learned to

adopt more adaptive ways of thinking.

Throughout the CBT sessions, a rapport was

established between Mr. X and the therapist,

creating a safe and supportive environment

for exploration and change. Clear goals were

set collaboratively between Mr. X and the

therapist, providing direction and motivation

for the therapeutic process. Regular

assessments were conducted to track Mr. X’s

progress and adjust the treatment plan as

needed. Overall, CBT proved to be an effective

intervention for Mr. X offering practical

strategies for reducing depressive symptoms,

modifying underlying beliefs, and improving

coping skills. By addressing the cognitive and

behavioural aspects of his depression, Mr X

was able to manage his mental health and

enhance his overall well-being.

We addressed internet addiction and

pornography use through cognitive

restructuring techniques within Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy (CBT). The client was

introduced to cognitive restructuring, which

helps in recognizing and modifying distorted

thought patterns that influence behavior. We

discussed how the client might use online

activities as a substitute for real-life selfesteem boosts and encouraged them to

identify when they use the internet as an

escape or to satisfy unmet needs rather than

addressing these needs directly. The session

focused on evaluating the rationality and

validity of the client’s current beliefs about

internet use and pornography. We also

worked on recognizing patterns of faulty

thinking, which will aid the client in challenging

these thoughts outside of therapy. The

discussion highlighted the difficulties in

justifying excessive internet use once the

client becomes aware of these thought

patterns and emphasized finding healthier

ways to meet unmet needs and build selfesteem without relying on the internet.

Techniques for stress management and urge

reduction, such as deep breathing and

progressive muscle relaxation, were

introduced. Additionally, mindfulness

strategies were taught to increase awareness

of emotional and behavioral patterns. By

integrating these mindfulness practices into

their daily routine, the client was encouraged

to build resilience against depressive and

anxious thoughts, ultimately enhancing their

emotional well-being. We developed a plan

for better time management to decrease

online time and boost real-life engagement.

The client demonstrated a willingness to

engage in cognitive restructuring and is

beginning to understand the link between

their thought patterns and internet use..

Family Interventions were provided focusing

on building parenting skills and promoting

positive parenting practices that can help to

reduce stress. Education was provided about

child development, his mental health status,

and realistic expectations of parenting that can

help reduce stress by aligning parental

expectations with reality.

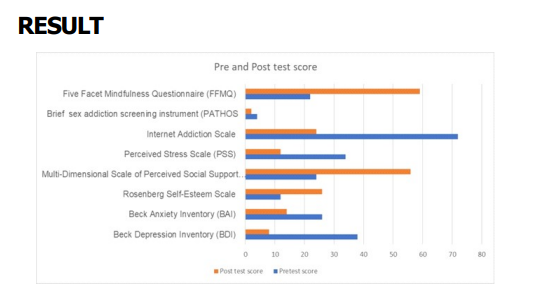

Figure 1 illustrates changes in pre- and postscore in the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Rosenberg SelfEsteem Scale, Multi-Dimensional Scale of

Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Perceived

Stress Scale (PSS) , Internet Addiction Scale,

Brief sex addiction screening instrument

(PATHOS and Five Facet Mindfulness

Questionnaire (FFMQ).

Psychosocial interventions were provided to

the patient, the session was mainly based on

cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), which

significantly improved the overall well-being

of the client. These interventions led to a

noticeable reduction in symptoms of

depression, anxiety, and stress. The psychosocial intervention specifically addressed

behavioural addictions such as internet

gaming and pornography in the client by

utilising CBT and mindfulness techniques, the

client saw notable improvements in postsession. Mindfulness-based strategies were

also implemented to help manage stress more

effectively. These comprehensive approaches

not only targeted the reduction of problematic

behaviours but also enhanced the client’s

ability to cope with daily stressors,

contributing to their mental health recovery

and improved quality of life. Cognitivebehavioral therapy (CBT) offers a potent

remedy for managing such stresses by helping

individuals identify and modify harmful

thought patterns that adversely affect their

behavior and emotions. Mindfulness-based

cognitive therapy (MBCT) also significantly

reduces depression symptoms in current

sufferers and is as effective as other

established treatments like group CBT

(Hofmann et al.,2012 and Strauss et al., 2014)

. Family interventions, too, play a crucial role.

After such interventions, there is often marked

improvement in mental health, with significant

reductions in depression, anxiety, and stress

observed. These interventions also help

families understand the illness better and

provide more supportive environments for the

patient. Support systems, particularly through

parental involvement and fostering positive

home environments, are vital for mitigating

academic stress. Adolescents with strong

parental support and minimal negative

interactions are better equipped with coping

skills (Klootwijk et al.,2021). illustrating the

importance of a nurturing home in combating

the adverse effects of academic pressures.

The findings highlight the efficacy of

psychosocial interventions, particularly

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), in

managing depression and behavioral

addictions, such as internet gaming and

pornography, in the client. These

interventions play a crucial role in alleviating

the impact of academic pressure and

addressing the underlying mental health

issues. Psychosocial approaches, including

CBT, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

(MBCT), and family therapy, are essential in

navigating the complex interplay of academic

stress, family dynamics, and mental health

challenges. By integrating these therapeutic

modalities, the treatment effectively mitigates

the negative effects of academic and familial

pressures, supports the client in overcoming

behavioral addictions, and fosters overall

emotional well-being. The comprehensive

nature of these interventions underscores

their importance in addressing multifaceted

issues and promoting sustainable recovery.

Baer R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J.,

Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006).

Using self-report assessment methods

to explore facets of mindfulness.

Assessment, 13(1), 27-45.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Beck Anxiety

Inventory Manual. San Antonio, TX:

Psychological Corporation

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock,

J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventor

for measuring depression. Archives of

General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561-571.

Carnes PJ, Green BA, Merlo LJ, Polles A,

Carnes S, Gold MS. PATHOS(2012) A

brief screening application for

assessing sexual addiction. J Addict

Med.6(1):29–34.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R.

(1983). A global measure of perceived

stress. Journal of Health and Social

Behavior, 24(4), 385-396.

Diamond G , Josephson A (2005) Family-based

treatment research: a 10-year

update . J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry . 44 : 872 – 887

[PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S.

(1983). The McMaster Family

Assessment Device. Journal of Marital

and Family Therapy, 9(2), 171-180.

Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, Davidson

RJ, Wampold BE, Kearney DJ, Simpson

TL(2018). Mindfulness-based

interventions for psychiatric disorders:

A systematic review and metaa n a l y s i s . C l i n i c a l

PsychologyReview59:52–60. [PMC

free article ] [PubMed] [Google

Scholar

Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT,

Fang A(2012). The efficacy of

cognitive behavioral therapy: a review

of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther

Res.36:427–440.

Klootwijk CLT, Koele IJ, van Hoorn J, Güroðlu

B, van Duijvenvoorde ACK.(2021)

Parental Support and Positive Mood

Buffer Adolescents’ Academic

Motivation During the COVID-19

Pandemic. J Res Adolesc.

Sep;31(3):780-795. doi: 10.1111/

jora.12660. PMID: 34448292; PMCID:

PMC8456955

McCance-Katz E. (2018) The substance abuse

and mental health services

administration (SAMHSA): new

directions. Psychiatr Serv. 69:1046–

8. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800281

[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the

adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne

D, Patton GC.(2018) The age of

adolescence. The Lancet Child &

Adolescent Health.;2(3):223–8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-

4642(18)30022-1

Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, Pettman

D( 2014). Mindfulness-based

interventions for people diagnosed

with a current episode of an anxiety

or depressive disorder: A metaanalysis of randomised controlled

trials. PLoSOne. 9(4):e96110. [PMC

free article ] [PubMed] [Google

Scholar]

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The

emergence of a new clinical disorder.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3),

237-244.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., &

Farley, G. K. (1988). The

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived

Social Support. Journal of Personality

Assessment, 52(1), 30-41