Background: Conduct Disorder (CD) is a childhood disorder marked by consistent anger, defiance,

and a desire for revenge. Children with CD struggle to control their emotions and actions. It

affects about 5-8% of children globally and typically starts between the ages of 10 and 18 years.

Methods and Materials: The three index clients, male, between 12-14 years of age, visited

the Institute of Psychiatry, Kolkata, with caregivers and were referred to the Psychiatric Social

Work department with the symptoms of stealing, lying, blaming, cruelty towards animals, anger

outbursts, hitting behavior towards others, and poor treatment adherence. Gradually titrating

the doses upwards, Tablet Risperidone upto a dose of 04 mg/day was prescribed to all of them.

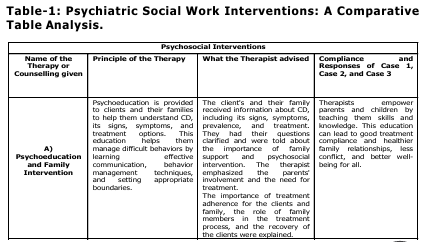

Following, the Psychiatric Social Worker imparted parent management training, behavior therapy,

parent-child interaction training, and anger management to the clients and family members.

Results: After the Psychiatric Social Work (PSW) interventions in combination with medication,

there were noticeable improvements in the lives and well-being of individuals with CD and their

families. The severity of CD symptoms decreased, high emotional expression decreased, and

family cohesion improved. Both clients and family members learned how to prevent recurrent

symptoms in future issues. Risperidone was tapered off in two individuals and in one, it was

reduced to 0.5 mg/day following the PSW interventions, once symptom control was achieved.

Conclusion: PSW interventions play a crucial role in managing Conduct Disorders (CD) by

involving the family. This approach helps in sustaining long-term well-being and improving

treatment (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) adherence.

Conduct disorder is a complex condition

marked by persistent behavioral and

emotional challenges in children. Those

children and adolescents find it hard to

adhere to rules, empathize with others, and

behave in socially acceptable ways, often leading to negative perceptions from peers,

adults, and social agencies. Diagnosing

Childhood Onset Conduct Disorder in young

children is challenging because they often

struggle to express their feelings. Symptoms

can vary depending on the child’s

developmental stage. For a diagnosis, at least

one symptom of conduct disorder must be

present before the age of 10(American

Psychiatric Association. (2013), these

symptoms may include aggression toward

people or animals (e.g., bullying, physical

fights, cruelty to animals), destruction of

property (e.g., deliberate fire-setting or

vandalism), deceitfulness or theft (e.g., lying

to obtain goods or favors, shoplifting), and

serious violations of rules (e.g., truancy from

school, running away from home). Identifying

these behaviors early is critical for timely

intervention and effective management.

Childhood Onset Conduct Disorder is

influenced by biological and psychosocial

factors and is more common in boys across

all groups. Associated social factors include

poverty, low socioeconomic status, parental

issues, poor education, weak community

support, academic struggles, and unstable

families (Loeber, R., & Keenan, K., 1994), also

included marital problems, inability to improve

their situation, poor discipline methods, lack

of interest in treatment, and mental health

challenges among family members (Sajadi et.

al.,2020). The prevalence of conduct disorders

affects 5-8% of all children, with a subset of

2-6% affected between ages 4 and 18. Among

youth under 18, CD rates are higher in boys

(6-16%) compared to girls (2-9%) (Gitonga

et.al., 2017). In India, it is found that the

prevalence of conduct disorders increased for

both males and females across all socio

economic groups, specifically, the increase

was noted at a rate of 4.58% for boys and

4.50% for girls (Agarwal & Sao,2014).

Various factors contribute to conduct

disorders, including genetics, academic

challenges, and the environment.

Understanding these factors is crucial for

supporting those affected by the disorder

(Scott, S, 2018). A chaotic home environment

with insufficient structure and supervision,

along with frequent parental conflicts, can lead

to problematic behavior in children. This may

result in harsh or punitive parenting,

negligence, exposure to domestic violence,

and an increased risk of neglect and emotional

instability for the child (American Psychiatric

Association. (2013). Early intervention is

crucial to prevent worsening antisocial

behavior in adulthood.

This study emphasizes the significance of

therapy for children with conduct disorder in

combination with medication. It investigates

whether PSW intervention can lessen problem

behavior, enhance family relationships, and

encourage treatment adherence. The aim is

to prevent recurrent symptoms in the future,

reduce caregiver stress, promote well-being

and treatment adherence, improve

communication patterns, and parent-child

relationships in the family.

Index client, 12 years old, Hindu, Bengali,

male, coming from semi urban area, low

socio-economic status, studied in class VI,

presenting with the complaints of demanding

behavior, hitting towards mother, use abusive

language for last 1 1D 2 years, Stealing,

laying, blaming for last 1.5 years, with

i nsidious onset, continuous course,

deteriorating progress, Poor treatment

compliance, Personal history revealed

behavioral problem like restlessness,

inattentive, limited number of friends, With

Family dynamics suggestive of diffuse

boundary, Parent child subsystem absent

between client and his father, non-verbal and

switch board communication present between client and his father, high noise levels.

Reinforcement is absent with inadequate

cohesiveness. Behavior observation revealed

i rritable affect, intact orientation, but

impaired memory function.

Index client, 12-year-old, Hindu, Bengali,

male, coming from semi urban area, low

socio-economic status, studied in class VI,

who has trouble following his parents’

instructions mostly, gets angry easily from 1.2

years demands a lot, harming his younger

brother from 1.8 years and shows aggressive

behavior towards animals and others and

excessively fond of mobile using from last 02

years with insidious onset, continuous course,

deteriorating progress, with poor treatment

compliance, Family dynamics appear to be

contributing to the client’s behavior, with a

diffuse boundary and poorly formed

subsystems between the parents and the

client and his brother. The father’s autocratic

l eadership style and the mother’s role

multiplicity. Interaction patterns within the

family are described as need-based and

strained, particularly with the younger

brother. High noise levels, emotional burden,

inadequate reinforcement, and cohesiveness

within the family environment are present.

There are personal history indicators such as

restlessness, inattention, limited friendships,

and difficulties with concentration and

memory.

Index client, 14-year-old, Hindu, Bengali, male

coming from rural area, low socio-economic

status, studied in class VII, has been showing

demanding behavior, hitting family members,

using abusive language for four years, and

setting fire at home, cruelty to animals,

stealing from home for the past two years,

with insidious onset, continuous course,

deteriorating progress with poor treatment

compliance, Personal history, he’s shown

temper tantrums towards classmates and has

only a few friends. Family dynamics indicate

a diffuse boundary, with his father as an

autocratic and nominal leader. Communication

with his father is non-verbal and a

switchboard. There’s a high noise level,

emotional burden present in the family, and

inadequate adaptive patterns. The mental

status examination displayed hand tremors.

He showed a delayed reaction time and

appeared irritable, with difficulties in attention

and concentration.

To help three adolescents with conduct

disorder, we start by understanding the causes

of their behavior through counseling and

checklists. Then, we provide tailored

interventions over 12 sessions, including

coping and social skill training individually and

family-level support like psychoeducation and

improving family interactions.

In the beginning, individual sessions focus on

building rapport. Then, over five sessions, the

approach becomes more directive. During the

assessment session, we observe both

behavioral excesses and deficits. Family

sessions

mainly

concentrate

on

psychoeducation and enhancing family

i nteraction patterns. This intervention

supports and addresses underlying issues.

Family intervention deals with family

dynamics, while individual counseling offers

personalized support. Overall, seven sessions

were needed for this intervention

During regular follow-up sessions, clients and

their families participated, with feedback

recorded, and Child Symptoms Inventory and

Family Attitude Scale assessments were

conducted. By the 12th session, clients showed

remarkable improvement, attending school

consistently and reducing problem behaviors.

Both parents expressed satisfaction with their

progress and were reminded of the

importance of consistent parenting. It has

been noticed that due to PSW intervention in

case 01 Risperidone dose was gradually

reduced to 0.5 mg/day and in case 02 & 03,

Risperidone was tapered off and stopped.

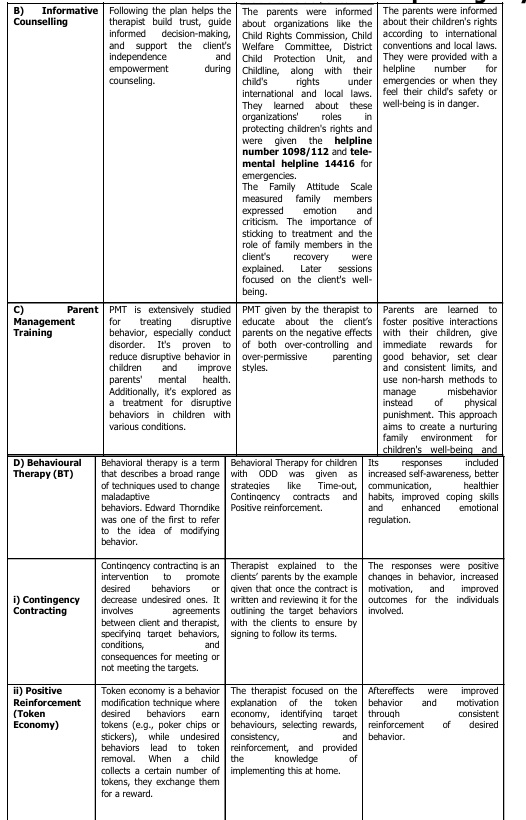

Table 2: Pre- and Post-Intervention

Assessment to measure the level of

severity of Conduct Disorder.

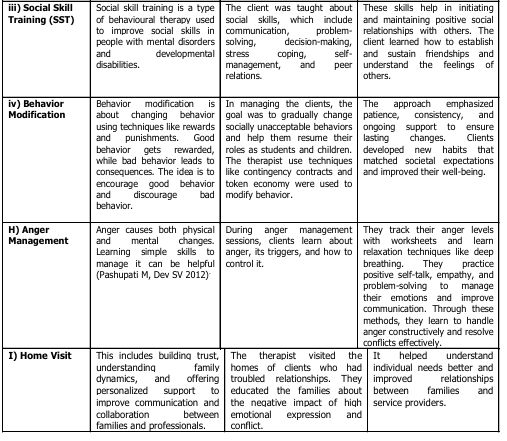

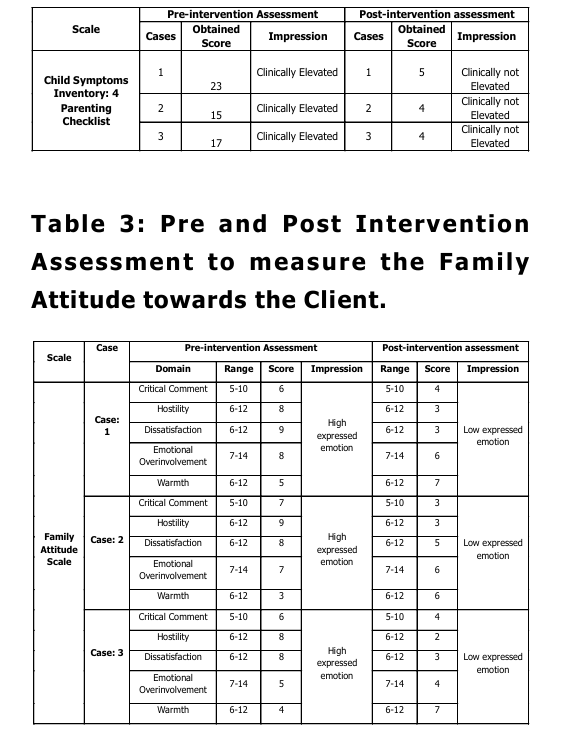

This study highlights the significant

improvements in both child behavior and

family dynamics following psychosocial

interventions for children with Conduct

Disorder (CD). Pre- and post-intervention

revealed a marked reduction in CD symptoms

and high-expressed emotions like critical

comments and hostility, alongside increased

positive expressed emotions like family

warmth, support, and positive interactions.

Tailored treatment plans, combining

psychotherapy, medication, and family

focused strategies, addressed the challenges

of CD, with Parent Management Training (PMT) playing a pivotal role in reshaping family

dynamics. By empowering parents with non

harsh disciplinary techniques and reinforcing

positive behaviors, these interventions

fostered stability, emotional bonding, and

structured routines at home. Behavioral

therapies, including Contingency Contracting,

Token Economy, and Social Skills Training,

enhanced emotional regulation and social

competence; while anger management

sessions helped children manage triggers and

conflicts effectively. Positive changes in

parental attitudes were observed early,

demonstrating the rapid impact of these

interventions. This study underscores the

importance of a comprehensive, family

inclusive approach and emphasizes the need

for sustainable support systems to maintain

progress.

However, achieving full healing requires

ongoing commitment and support.

Researchers, like Helander et al. (2022),

agree with this study’s findings. They support

the effectiveness of combining Parent

Management Training (PMT) with Cognitive

Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for children with

Conduct Disorder (CD) and their families.

Similarly, A study by Loeber and Keenan

(1994) found that psychosocial interventions,

including Parent Management Training (PMT),

significantly improved children with Conduct

Disorder (CD) and their families. These

interventions helped address family dynamics,

stabilize routines, and encourage positive

behavior. Positive changes in parental behavior

were observed after just a few sessions,

showing the effectiveness of the approach. A

study also aligns with this, showing a link

between expressed emotion, caregivers’

stress, and the child’s self-sufficiency

(Balachandran et. al., 2023). No studies

contradict these results or the treatment

approach used in this study.

CONCLUSION

Our investigation has uncovered the profound

impact of psychiatric social work interventions

in combination with medication on children

struggling with Conduct Disorders (CD) and

t heir families. Through the strategic

application of therapeutic techniques such as

Parent Management Training (PMT),

Behavioral Therapy (BT), and Anger

Management, we witnessed significant strides

forward. The effects of these interventions

were not confined to the individual children

alone; rather, they resonated throughout the

familial ecosystem. Observable changes in the

children’s behavior included a palpable

reduction in disruptive tendencies and a

notable enhancement in academic

performance, underscoring the efficacy of our

therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the

ripple effect extended to the dynamics within

the family unit. Decreased discord and

heightened cohesion emerged as hallmarks of

the familial transformation, contributing not

only to a more harmonious domestic

environment but also to the overall well-being

of each family member. Of particular

significance was the assimilation of preventive

measures by both children and their families.

Empowered with new strategies and coping

mechanisms, they found themselves better

equipped to confront the complexities of

future challenges with resilience and

determination, thereby laying a sturdy

foundation for sustained growth and progress.

Agarwal, M., Hemadri, K., & Sao. (2014).

Conduct disorder among adolescents:

An intervention approach through

psycho-yogic

program. The

International Journal of Indian

Psychology, 2(1), 269–271. https://

ijip.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/

10-M-Agarwal-H-Sao.pdf

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

(1997). Practice

parameters for the assessment and

treatment of children and adolescents

with conduct disorder. Journal of the

American Academy of Child &

Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(10 Suppl),

122S–139S. https://doi.org/10.1097/

00004583-199710001-00008

American Psychiatric Association.

(2021). Diagnostic and statistical

manual of mental disorders (DSM-5).

American Psychiatric Publishing.

Balachandran, K. P., & Bhuvaneswari, M.

(2023). Expressed emotion in families

of children with neurodevelopmental

disorders: A mixed-method approach.

Annals of Neurosciences. https://

doi.org/10.1177/09727531231181014.

Gitonga, M., Muriungi, S., & Ongaro, K.

(2017). Prevalence of conduct

disorder among adolescents in

secondary schools: A case of

Kamukunji and Olympic mixed sub

County secondary schools in Nairobi

County, Kenya. African Journal of

Clinical Psychology, 1, 100. https://

www.daystar.ac.ke/ajcp/download/6/

1662453869_Prevalence-of-Conduct

Disorder-among-Adolescents-in

Secondary-Schools.pdf

Helander, M., Asperholm, M., Wetterborg, D.,

Öst, L., Hellner, C., Herlitz, A., &

Enebrink, P. (2022). The efficacy of

parent management training with or

without involving the child in the

treatment among children with clinical

levels of disruptive behavior: A meta

analysis. Child Psychiatry & Human

Development, 55(1), 164-181. https:/

/doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01367

y

Loeber, R., & Keenan, K. (1994). Interaction

between conduct disorder and its

comorbid conditions: Effects of age

and gender. Clinical Psychology

Review, 14(6), 497–523. https://

d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 / 0 2 7 2

7358(94)90015-9

Pashupati, M., & Dev, S. V. (2012). Anger and

its management. Journal of Nobel

Medical College, 1(1), 9–14.

Sajadi, S., Raheb, G., Maarefvand, M., &

Alhosseini, K. A. (2020). Family

problems associated with conduct

disorder perceived by patients,

families, and professionals. Journal of

Education and Health Promotion, 9,

184. https://doi.org/10.4103/

jehp.jehp_110_20

Scott S. Conduct disorders. In Rey JM (ed),

IACAPAP e-Textbook of Child and

Adolescent Mental Health. Geneva:

International Association for Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied

Professions, 2012.