Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

Menu

A SCOPING REVIEW OF THE EXPERIENCES OF WOMEN TO

WOMEN BULLYING IN WORKSPACES

Sushma Kumari1

, Kalindi Sharma2

, Ranjeet Kumar3

, Akanksha Sharma4

,

Sheelu Yadav5

, Rajinder K. Dhamija6

1Project Director & Assistant Professor (Social Work), Department of Human Behaviour, IHBAS,

Delhi, 2

Assistant Professor (Social & Cultural Anthropology), Department of Human Behaviour,

IHBAS, Delhi,3Associate Professor (Clinical Psychology), Gwalior Mansik Arogyashala, Gwalior,

M.P., 4Research Associate (ICSSR Funded Study), Department of Human Behaviour, IHBAS, Delhi,

5Field Investigator (ICSSR Funded Study), Department of Human Behaviour, IHBAS, Delhi, 6Professor

& Director, IHBAS, Delhi -110095

Correspondence: Sushma Kumari, E-mail: sushma_cip@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

Bullying, as an aggressive behaviour, introduces a power dynamic between two or more individuals

that often brings about hostility between individuals, especially a lack of collegiality within the

workspace. This has adverse ramifications for the people involved in this skewed work dynamics

as not only the productivity is affected but there are consequent impacts on the mental health of

the perpetrator and the victim alike. Within the conventional patriarchal constructs, women are

most easily taken as the victims of violence (verbal or otherwise) and aggression perpetrated by

men, which means that more concealed forms of aggression and hostility existing within the

gender is never brought to the centre. However, there have been several instances of women-towomen bullying at the workplace and within the households, which has further marginalized

their status and affected their ability to work peacefully and effectively.

This paper is a rigorous and extensive scoping review of the literature on women-to-women

bullying in workspaces. The review of the literature spans across a course of 20 years beginning

from the years 2003 to 2023. The literature review method adheres to Joanna Briggs Institute’s

(JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis and the PRISMA-P Guidelines for enhanced data selection

and synthesis. The scoping review of the literature was restricted to only peer-reviewed journal

articles as opposed to non-periodic publications and grey literature to ensure academic rigor.

The review revealed that bullying at workspaces is an aggressive behaviour that results from

complex power dynamics between employees. When the phenomenon of bullying is explored

from a gendered lens, especially women to women bullying, it is evident that the status of

women becomes even more vulnerable owing to the fear of being sidelined and overlooked by a

fellow female colleague in a workspace that is generally dominated by male counterparts and

male decision-makers. However, such findings cannot be generalized across educational status,

varied socio-demographic profiles, nature of employment, and several other key denominators.

INTRODUCTION

Bullying among women at the workplace is not as uncommon and a rare occurrence as it may seem, it is a worryingly common phenomenon that demands our immediate attention. Its adverse effects have ramifications for the entire organization, making it a pressing concern for all. Power dynamics at work are not limited to one’s status or position within an organization but it extends to the positionality of an individual within the social matrix of the workspace. This positionality is a key factor in how bullying manifests in the behavioural pattern of the individuals and their subsequent interactions with their colleagues at the workplace. At its core, bullying is the use of intimidating tactics to assert dominance, ranging from verbal aggression and threats to physical abuse and coercion. Workplace bullying is a dehumanizing process that revolves around power and control and this behaviour fosters an extremely non-conducive environment where employees feel unsafe, undermined, and unable to flourish professionally. It not only puts an employee’s professional credibility under question, but also their character, dignity, and overall integrity as a human being is marred with suspicion. It can be an intensely traumatic experience. Workplace bullying is the systematic mistreatment of an individual over an extended period, making it difficult for the individual to defend themselves (Einarsen et al., 2020). Research indicates that working women are at a higher risk of experiencing bullying compared to their male counterparts. However, women tend to self-identify as being bullied more frequently than men (Salin, 2001, 2018). One possible reason might be that women generally hold far less social control and power in comparison to men (Miner & Eischeid, 2012; Salin, 2018). In such a scenario of inequality, those in power may attempt to uphold the disparity by openly discriminating and engaging in various hostile behaviours towards the less powerful (Sidanius et al., 2004). Furthermore, several studies have shown that women in higher managerial positions are more likely to be bullied (Hoel et al., 2001). Salin (2001) proposed that there is a correlation between women in formal positions and bullying behaviour, which suggests that women in managerial roles experience bullying more often than their male counterparts in a similar position. This may be attributed to the fact that women are typically a minority in managerial positions, making them more noticeable and at the same time more vulnerable to being bullied, owing to their visibility. Evidence supports this, as Hoel et al. (2001) found that nearly 16% of female senior managers reported to being bullied, whereas only around 6% of male senior managers reported the same. Additionally, a similar trend was observed when there is a role reversal in services that are mostly dominated by women, men being in minority, has been identified as a contributing factor to higher levels of bullying for men in femaledominated fields, such as nursing (Eriksen & Einarsen, 2004), public service (Wang & Hsieh, 2015), and childcare (Lindroth & Leymann, 1993). Workplace bullying impacts women worldwide, with a range of health, social, and economic concerns (Van De Griend & Messias, 2014). The vast majority of international studies on workplace bullying have used limited to no psychometric measures to thoroughly understand bullying (Nielsen et al., 2011), leaving little room to account for variations in the level of exposure to bullying. Bullying at the workplace is characterized by its cyclical nature (Einarsen et al., 2011). Bowling and Beehr (2006) examined the practice from the viewpoint of victims of bullying and claimed that this aggressive and threatening behaviour may be directed towards the victims due to their tendency to stand out in the crowd, it may also be due to other circumstances, which could result in disputes. Bullying at the workplace is a systemic issue because bullying affects the entire system rather than just the victim and the offender (Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006). Victims of workplace bullying have unique characteristics and the circumstances around them can both cause harassment and bullying, which may lead to arguments (Bowling & Beehr, 2006). More than two-thirds of female bullies (sometimes known as “mean girls”) specifically target other women (Irby, 2019). According to Martinek (2023), up to 80% of workplace bullying is caused by hostility between women. The use of covert narcissistic methods by a female bully to harass her female colleagues at the workplace is a commonplace practice. She also noticed that the root causes of this narcissistic behaviour frequently stem from ingrained emotions of insecurity and rivalry at the workplace. Harvey (2018) reports that bullying, abuse, and job disruption are more common among women. Furthermore, Harvey has also explored the Queen Bee Syndrome among women that intimidate, undermine, or demoralize others they work with. The Queen Bee is not to be compared with a strong, professionally driven woman at the official space, who needs to make her presence known which may possibly upset some people in the process. Admittedly, women in positions of power and authority harshly treat their subordinate female colleagues, compared to their subordinate male staff members (Derks, Van Laar & Ellemers, 2016). According to the fourth Workplace Bullying Survey (2017) conducted in the United States by Gary Namie, it was found that 66% of all the victims of bullying were women and 70% of all the perpetrators of this hostile conduct were men. However, bullying is also committed by women against other women in 67% cases and men against women colleagues in 65% cases. The instances of woman-to-woman bullying were found to be disproportionately high against the usual prevalence in previous WBI national surveys. Therefore, in order to direct efforts to eliminate bullying, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of this type of intragender bullying prevalent among women. Moreover, women target other women twice as frequently as they target men. Akella, (2016) and Lutgen-Sandvik, et.al. (2012) have defined workplace bullying as “repeated and persistent negative actions towards one or more individual(s), which involve a perceived power imbalance and create a hostile work environment.” Within the Indian context, bullying is often considered a masculine affair but the practice of women-to-women bullying can be found in literally every domain beginning with the home turf wherein hostility between a woman and her daughter-in-law is generally realised, and perceived by every other married woman. The prevalence of woman-to-woman bullying is so deeply entrenched within the female consciousness, that it is often normalized as an inevitable behaviour in a professional environment. The style of bullying that women practice within a workspace is typically restrained, sly, and unobtrusive making it a challenge to identify. In short, the female workplace bullying is, perhaps “bullying by stealth” and is likely never understood with the same veracity as bullying practiced by men towards women colleagues as the consequences of inter-gender hostility are considered far more severe, and can escalate to sexual harassment. D’Cruz and Rayner (2013) state that compared to other countries, India lacks academic research on the subject, and limited information is available about the nature, prevalence, and extent of bullying. Given these sociocultural developments, bullying at work has emerged as one of the primary problems Indian workers face today. There has been a noticeable shift in the Indian work culture with regard to stress at work and the availability of new positions due to the globalising economy and the influx of multinational corporations (Budhwar, et al., 2006). Bullying is one of the major issues that plagues the employees in India working in various sectors, however, it is typically not reported by the victims as it not only raises a question on the conduct of an employee who is bullying others, but it also brings about the question of safety of the employees at the workplace which gives a semblance of hostility at the organization and its inability to provide a safe redressal mechanism to the victims (Bairy, et al. 2007). Despite confirmed reports of bullying phenomena being prevalent in India as well, research and theory on the notion that women bully other women frequently, still has a long way to go, particularly in the case of India (D’Cruz and Noronha, 2010). The findings of D’Cruz and Rayner’s (2013) investigative research into the ITES-BPO industry in India confirmed that, in comparison to the Nordic and other European countries, workplace bullying is more prevalent in India. Ciby and Raya (2014) report that bullying was primarily committed by superiors, which is in line with India’s hierarchical structure. When individuals witness acts of bullying, their first and most immediate reaction is to experience negative feelings like anger and frustration. Nonetheless, the impacts of bullying can be addressed by colleagues who witness the act of bullying and are willing to come forward and report it to a complaints committee or to higher authorities designated to address such cases (Gholipour, et al., 2011). This paper highlights the key findings in the literature with regard to women to women bullying at the workplace.

Bullying among women at the workplace is not as uncommon and a rare occurrence as it may seem, it is a worryingly common phenomenon that demands our immediate attention. Its adverse effects have ramifications for the entire organization, making it a pressing concern for all. Power dynamics at work are not limited to one’s status or position within an organization but it extends to the positionality of an individual within the social matrix of the workspace. This positionality is a key factor in how bullying manifests in the behavioural pattern of the individuals and their subsequent interactions with their colleagues at the workplace. At its core, bullying is the use of intimidating tactics to assert dominance, ranging from verbal aggression and threats to physical abuse and coercion. Workplace bullying is a dehumanizing process that revolves around power and control and this behaviour fosters an extremely non-conducive environment where employees feel unsafe, undermined, and unable to flourish professionally. It not only puts an employee’s professional credibility under question, but also their character, dignity, and overall integrity as a human being is marred with suspicion. It can be an intensely traumatic experience. Workplace bullying is the systematic mistreatment of an individual over an extended period, making it difficult for the individual to defend themselves (Einarsen et al., 2020). Research indicates that working women are at a higher risk of experiencing bullying compared to their male counterparts. However, women tend to self-identify as being bullied more frequently than men (Salin, 2001, 2018). One possible reason might be that women generally hold far less social control and power in comparison to men (Miner & Eischeid, 2012; Salin, 2018). In such a scenario of inequality, those in power may attempt to uphold the disparity by openly discriminating and engaging in various hostile behaviours towards the less powerful (Sidanius et al., 2004). Furthermore, several studies have shown that women in higher managerial positions are more likely to be bullied (Hoel et al., 2001). Salin (2001) proposed that there is a correlation between women in formal positions and bullying behaviour, which suggests that women in managerial roles experience bullying more often than their male counterparts in a similar position. This may be attributed to the fact that women are typically a minority in managerial positions, making them more noticeable and at the same time more vulnerable to being bullied, owing to their visibility. Evidence supports this, as Hoel et al. (2001) found that nearly 16% of female senior managers reported to being bullied, whereas only around 6% of male senior managers reported the same. Additionally, a similar trend was observed when there is a role reversal in services that are mostly dominated by women, men being in minority, has been identified as a contributing factor to higher levels of bullying for men in femaledominated fields, such as nursing (Eriksen & Einarsen, 2004), public service (Wang & Hsieh, 2015), and childcare (Lindroth & Leymann, 1993). Workplace bullying impacts women worldwide, with a range of health, social, and economic concerns (Van De Griend & Messias, 2014). The vast majority of international studies on workplace bullying have used limited to no psychometric measures to thoroughly understand bullying (Nielsen et al., 2011), leaving little room to account for variations in the level of exposure to bullying. Bullying at the workplace is characterized by its cyclical nature (Einarsen et al., 2011). Bowling and Beehr (2006) examined the practice from the viewpoint of victims of bullying and claimed that this aggressive and threatening behaviour may be directed towards the victims due to their tendency to stand out in the crowd, it may also be due to other circumstances, which could result in disputes. Bullying at the workplace is a systemic issue because bullying affects the entire system rather than just the victim and the offender (Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006). Victims of workplace bullying have unique characteristics and the circumstances around them can both cause harassment and bullying, which may lead to arguments (Bowling & Beehr, 2006). More than two-thirds of female bullies (sometimes known as “mean girls”) specifically target other women (Irby, 2019). According to Martinek (2023), up to 80% of workplace bullying is caused by hostility between women. The use of covert narcissistic methods by a female bully to harass her female colleagues at the workplace is a commonplace practice. She also noticed that the root causes of this narcissistic behaviour frequently stem from ingrained emotions of insecurity and rivalry at the workplace. Harvey (2018) reports that bullying, abuse, and job disruption are more common among women. Furthermore, Harvey has also explored the Queen Bee Syndrome among women that intimidate, undermine, or demoralize others they work with. The Queen Bee is not to be compared with a strong, professionally driven woman at the official space, who needs to make her presence known which may possibly upset some people in the process. Admittedly, women in positions of power and authority harshly treat their subordinate female colleagues, compared to their subordinate male staff members (Derks, Van Laar & Ellemers, 2016). According to the fourth Workplace Bullying Survey (2017) conducted in the United States by Gary Namie, it was found that 66% of all the victims of bullying were women and 70% of all the perpetrators of this hostile conduct were men. However, bullying is also committed by women against other women in 67% cases and men against women colleagues in 65% cases. The instances of woman-to-woman bullying were found to be disproportionately high against the usual prevalence in previous WBI national surveys. Therefore, in order to direct efforts to eliminate bullying, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of this type of intragender bullying prevalent among women. Moreover, women target other women twice as frequently as they target men. Akella, (2016) and Lutgen-Sandvik, et.al. (2012) have defined workplace bullying as “repeated and persistent negative actions towards one or more individual(s), which involve a perceived power imbalance and create a hostile work environment.” Within the Indian context, bullying is often considered a masculine affair but the practice of women-to-women bullying can be found in literally every domain beginning with the home turf wherein hostility between a woman and her daughter-in-law is generally realised, and perceived by every other married woman. The prevalence of woman-to-woman bullying is so deeply entrenched within the female consciousness, that it is often normalized as an inevitable behaviour in a professional environment. The style of bullying that women practice within a workspace is typically restrained, sly, and unobtrusive making it a challenge to identify. In short, the female workplace bullying is, perhaps “bullying by stealth” and is likely never understood with the same veracity as bullying practiced by men towards women colleagues as the consequences of inter-gender hostility are considered far more severe, and can escalate to sexual harassment. D’Cruz and Rayner (2013) state that compared to other countries, India lacks academic research on the subject, and limited information is available about the nature, prevalence, and extent of bullying. Given these sociocultural developments, bullying at work has emerged as one of the primary problems Indian workers face today. There has been a noticeable shift in the Indian work culture with regard to stress at work and the availability of new positions due to the globalising economy and the influx of multinational corporations (Budhwar, et al., 2006). Bullying is one of the major issues that plagues the employees in India working in various sectors, however, it is typically not reported by the victims as it not only raises a question on the conduct of an employee who is bullying others, but it also brings about the question of safety of the employees at the workplace which gives a semblance of hostility at the organization and its inability to provide a safe redressal mechanism to the victims (Bairy, et al. 2007). Despite confirmed reports of bullying phenomena being prevalent in India as well, research and theory on the notion that women bully other women frequently, still has a long way to go, particularly in the case of India (D’Cruz and Noronha, 2010). The findings of D’Cruz and Rayner’s (2013) investigative research into the ITES-BPO industry in India confirmed that, in comparison to the Nordic and other European countries, workplace bullying is more prevalent in India. Ciby and Raya (2014) report that bullying was primarily committed by superiors, which is in line with India’s hierarchical structure. When individuals witness acts of bullying, their first and most immediate reaction is to experience negative feelings like anger and frustration. Nonetheless, the impacts of bullying can be addressed by colleagues who witness the act of bullying and are willing to come forward and report it to a complaints committee or to higher authorities designated to address such cases (Gholipour, et al., 2011). This paper highlights the key findings in the literature with regard to women to women bullying at the workplace.

Objectives

1. The scope of the study regarding the prevalence of bullying and the resulting mental harassment among women at their workspaces.

2. Reasons for bullying and mental harassment inflicted upon women by their female colleagues are being investigated in the study.

3. Method of assessment of the impact of bullying and mental harassment on the mental and emotional well-being of women.

4. The socio-demographic factors that were used to evaluate the degree to which women employees have been victimized owing to their varied sociodemographic profiles.

5. Preferred coping strategies and their effectiveness.

In order to carry out this scoping review, the literature was statistically synthesized and an overview of the empirical evidence surrounding the bullying of women at work was taken into account, which holds a significant impact on the psycho-social wellbeing of women, their coping strategies, and redressal strategies. In addition to highlighting knowledge gaps, a comprehensive synthesis of the literature will give readers, an overview of what has already been done and understood in this research domain. Therefore, in addition to being extremely pertinent to the work culture ethos, the current study will offer crucial guidance for the future course of research.

1. The scope of the study regarding the prevalence of bullying and the resulting mental harassment among women at their workspaces.

2. Reasons for bullying and mental harassment inflicted upon women by their female colleagues are being investigated in the study.

3. Method of assessment of the impact of bullying and mental harassment on the mental and emotional well-being of women.

4. The socio-demographic factors that were used to evaluate the degree to which women employees have been victimized owing to their varied sociodemographic profiles.

5. Preferred coping strategies and their effectiveness.

In order to carry out this scoping review, the literature was statistically synthesized and an overview of the empirical evidence surrounding the bullying of women at work was taken into account, which holds a significant impact on the psycho-social wellbeing of women, their coping strategies, and redressal strategies. In addition to highlighting knowledge gaps, a comprehensive synthesis of the literature will give readers, an overview of what has already been done and understood in this research domain. Therefore, in addition to being extremely pertinent to the work culture ethos, the current study will offer crucial guidance for the future course of research.

METHODOLOGY

In order to carry out scoping review of the existing literature, the following methodological framework was followed – The overall parameters for umbrella review provided in the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis have been followed in the framework of the present study. Additionally, this review was carried out using the PRISMA-P Guidelines for enhanced data selection and data synthesis using PRISMA-P viz. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (Moher et al., 2015; Stroup et al., 2000). The review primarily revolved around the questions about the characteristics of workplace bullying based on gender; the influence of workplace bullying in women’s lives at the workplace; and strategies employed by women to respond to workplace bullying. Essentially, our search included conceptual and empirical publications about workplace harassment of women by other women. Published articles were included as one of the subsequent parameters. The review included publications that were released between January 2003 and December 2023 in order to maintain contiguity of the literature with the contemporary times. The search results were exported to the Covidence database, an online screening and data extraction tool designed for writers of systematic reviews. Research papers were selected based on the title and abstract to determine whether they were likely to give relevant information on workplace bullying of women after excluding grey literature. Following this step, the content of the selected paper was screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Based on the authenticity and relevance to the research questions multiple databases were accessed for instance PubMed, EBSCO, JSTOR, APA PsycInfo, and Mesh. The search terms were variants of terms like bullying of women by women at workplace, woman-to-woman bullying at work, and workplace bullying by women. Each database search included results in English from both national and international publications.

In order to carry out scoping review of the existing literature, the following methodological framework was followed – The overall parameters for umbrella review provided in the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis have been followed in the framework of the present study. Additionally, this review was carried out using the PRISMA-P Guidelines for enhanced data selection and data synthesis using PRISMA-P viz. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (Moher et al., 2015; Stroup et al., 2000). The review primarily revolved around the questions about the characteristics of workplace bullying based on gender; the influence of workplace bullying in women’s lives at the workplace; and strategies employed by women to respond to workplace bullying. Essentially, our search included conceptual and empirical publications about workplace harassment of women by other women. Published articles were included as one of the subsequent parameters. The review included publications that were released between January 2003 and December 2023 in order to maintain contiguity of the literature with the contemporary times. The search results were exported to the Covidence database, an online screening and data extraction tool designed for writers of systematic reviews. Research papers were selected based on the title and abstract to determine whether they were likely to give relevant information on workplace bullying of women after excluding grey literature. Following this step, the content of the selected paper was screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Based on the authenticity and relevance to the research questions multiple databases were accessed for instance PubMed, EBSCO, JSTOR, APA PsycInfo, and Mesh. The search terms were variants of terms like bullying of women by women at workplace, woman-to-woman bullying at work, and workplace bullying by women. Each database search included results in English from both national and international publications.

ELIGIBILITY (INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION)

CRITERIA

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study were developed in light of the research questions. More precisely, the “DS-CPC” format—which takes into account factors pertaining to Documents, Studies, Construct, Participants, and Contexts—was used to develop a protocol.

a) Based on the type of documents: For the purpose of this review, the selection encompassed only one category of documents that is periodical publications i.e. scholarly journal articles. The document types that were excluded are master’s or bachelor’s theses, editorials, case reports, technical notes, newspaper articles, communications, obituaries, and any other literature that can fit within these categories. Furthermore, our exclusion criteria also applied to non-periodic publications including novels, book chapters, and published doctoral theses. In order to guarantee that the research review offers a thorough picture of the phenomena of bullying within the academic discourse, this exclusion technique was used to concentrate on sources that offered the strongest, peerreviewed evidence.

b) Based on type of research: The literature under review primarily focused on content analysis, case studies, empirical studies, reviews such as narrative reviews, scoping reviews, focused mapping reviews, rapid reviews, integrative reviews, and metasyntheses, often referred to as umbrella review.

c) Based on the content of research: The focus of the research review was restricted to domains like workspace bullying, workplace inequity, organizational hostility, psychological health of employees, bullying of women, hostile workspaces for women etc. With the above protocol as a guiding framework, 19389 articles were found on the search engine as part of the primary search.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study were developed in light of the research questions. More precisely, the “DS-CPC” format—which takes into account factors pertaining to Documents, Studies, Construct, Participants, and Contexts—was used to develop a protocol.

a) Based on the type of documents: For the purpose of this review, the selection encompassed only one category of documents that is periodical publications i.e. scholarly journal articles. The document types that were excluded are master’s or bachelor’s theses, editorials, case reports, technical notes, newspaper articles, communications, obituaries, and any other literature that can fit within these categories. Furthermore, our exclusion criteria also applied to non-periodic publications including novels, book chapters, and published doctoral theses. In order to guarantee that the research review offers a thorough picture of the phenomena of bullying within the academic discourse, this exclusion technique was used to concentrate on sources that offered the strongest, peerreviewed evidence.

b) Based on type of research: The literature under review primarily focused on content analysis, case studies, empirical studies, reviews such as narrative reviews, scoping reviews, focused mapping reviews, rapid reviews, integrative reviews, and metasyntheses, often referred to as umbrella review.

c) Based on the content of research: The focus of the research review was restricted to domains like workspace bullying, workplace inequity, organizational hostility, psychological health of employees, bullying of women, hostile workspaces for women etc. With the above protocol as a guiding framework, 19389 articles were found on the search engine as part of the primary search.

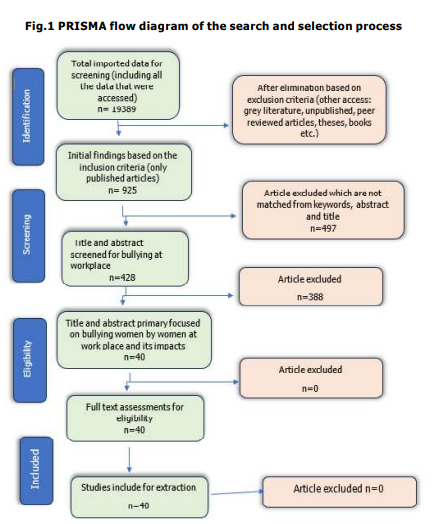

The above inclusion criteria were applied to

limit the literature based on its content and

relevance to the scoping review, which came

to be 925 research papers. Out of these 925

papers, 40 research articles and scholarly

papers were shortlisted for full-text scoping

review after a second round of title and

abstract review to ascertain whether bullying

of women by women at the workplace was

the main subject of the papers. All 40

references satisfied the inclusion criteria after

a full text review. A flow diagram of the

selection process, adapted from PRISMA

statement guidelines, is depicted in (Fig.1).

Data on reference information (authors,

publication year, journal, title), sample

characteristics, geographical origin of the

study, study design, theoretical framework,

number of participants, response rate, mean

age, sampling procedure, tools for measuring

bullying of women by women at the workplace,

and overlap in the sample with other studies

in the review were all independently extracted

using a standardized format. Every database

search yielded results from both domestic and

international publications and articles in the

English language and those that could be

translated in English. The data in the selected

40 articles were coded and the coding scheme

was refined till discrepancies were addressed

and concordance was reached after multistage screening of the data.

DATA SYNTHESIS

The literature revealed that women have been bullying other women in the workplace in a number of ways. Theoretically, women, in particular, have a tendency to value interactions with other women at the workplace owing to a number of reasons, for instance, in most sectors women are underrepresented and require a support network within their gender, they are less likely to reach managerial and administrative positions when compared with their male counterparts. Some of the victim accounts in the publications highlighted coping mechanisms that included support networks, organizational lobbying, and workplace bullying prevention and eradication policies. Additionally, publications were tagged for the following genres of workplace bullying of women by women. This includes social relationships, work environments, women’s health, and victimization.

The literature revealed that women have been bullying other women in the workplace in a number of ways. Theoretically, women, in particular, have a tendency to value interactions with other women at the workplace owing to a number of reasons, for instance, in most sectors women are underrepresented and require a support network within their gender, they are less likely to reach managerial and administrative positions when compared with their male counterparts. Some of the victim accounts in the publications highlighted coping mechanisms that included support networks, organizational lobbying, and workplace bullying prevention and eradication policies. Additionally, publications were tagged for the following genres of workplace bullying of women by women. This includes social relationships, work environments, women’s health, and victimization.

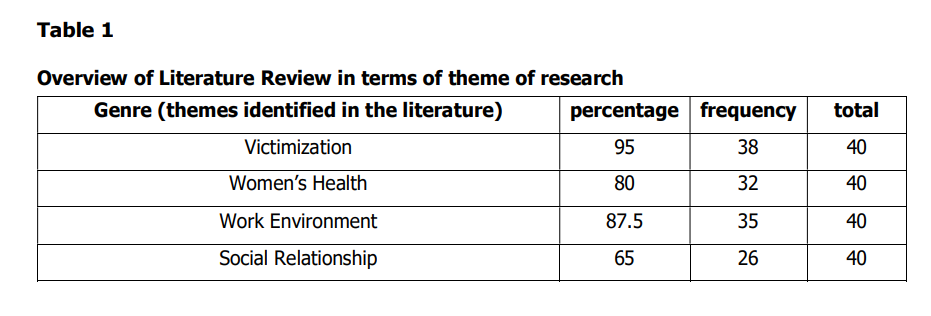

Table 1 provides an overview of the different

outcomes that have been examined in the

literature under review. Victimization of

women employees as a result of bullying was

the most frequently examined genre in 38

articles. The theme of women’s health

including their mental health complaints (e.g.,

anxiety and depression) were also found in

32 studies. Work environments was a

prominent theme in 35 studies, whereas social

network was a dominant theme in 26 articles.

SALIENT FEATURES OF THE LITERATURE

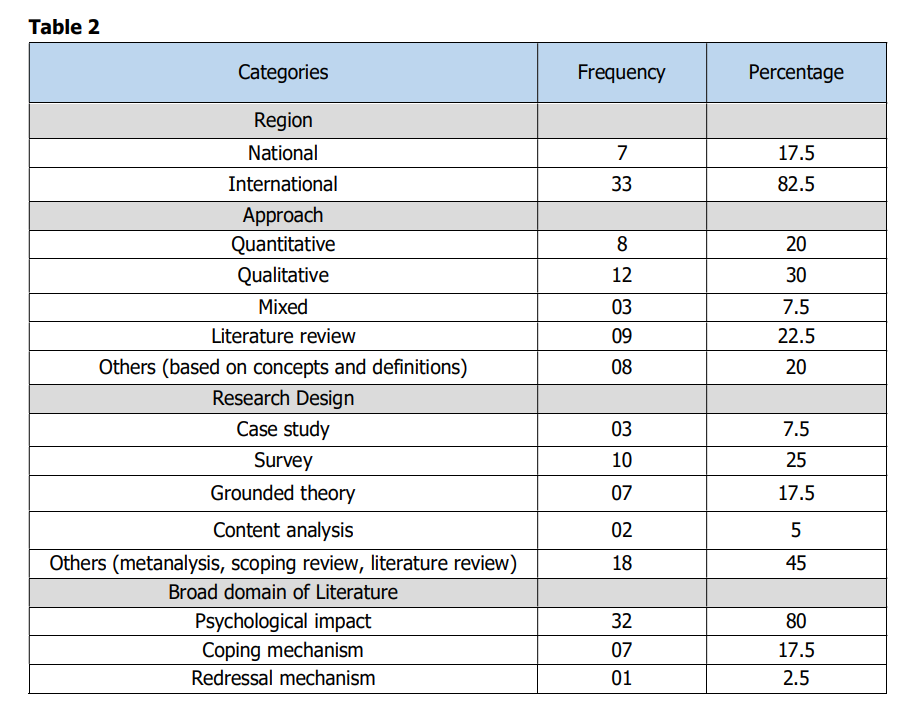

Both national and international journal articles were included in the review and Table 2 provides an overview of the different outcomes that have been examined in research pertaining to bullying of women by women at workplace. Out of the 40 articles, 7 are from national journal and 33 are from international journal. The articles belong to 17 countries namely Bangladesh, South Africa, Brazil, Verginia, Australia, Romania, Netherland, Sydney, Iran, India, Canada, Finland, Italy, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States of America.

Both national and international journal articles were included in the review and Table 2 provides an overview of the different outcomes that have been examined in research pertaining to bullying of women by women at workplace. Out of the 40 articles, 7 are from national journal and 33 are from international journal. The articles belong to 17 countries namely Bangladesh, South Africa, Brazil, Verginia, Australia, Romania, Netherland, Sydney, Iran, India, Canada, Finland, Italy, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States of America.

Methodologically, out of the total 40 articles,

the methodological framework of 12 articles

followed a qualitative approach and 8 articles

followed a quantitative approach.

Furthermore, 9 studies include literature

review, 3 articles have adopted a mixed

methods approach and 8 articles deal with

qualifying and defining terms that are regularly

used in studying the phenomenon of bullying.

In terms of a research design, 10 articles

adopted a survey research design, 3 articles

are based on case study design, 7 are based

on grounded theory research design, 2

articles are based on content analysis, and

the rest 18 articles can be categorized into

two broad domains, 10 articles include either

literature reviews, metanalyses, or scoping

review, while the remaining 8 articles are

conceptually exploring the phenomenon of

hostile workspaces. Broadly, the domains of

all 40 articles may be divided into

psychological impact of bullying, coping

mechanism of victims of bullying, and redressal of such grievances at the level of

organizations.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have delved into the prevalence of bullying, yet relatively few have focused specifically on intra-gender bullying, which refers to bullying that occurs between individuals of the same gender. Notably, instances of bullying perpetrated by females against other females often go unreported even though such occurrences are significant in number. Research examining the experiences of individuals subjected to bullying have revealed compelling evidences in support of women to women bullying. Admittedly, women are far more likely than males to encounter challenging behaviours at workspaces, including refusal to cooperate with them and non-collegial interactions with fellow employees. Furthermore, they often experience disrespectful, disruptive, or outright rude behaviours that their male counterparts seldom experience (Lampman, 2012). In a significant study conducted by Salin (2001), the impact of gender on workplace bullying was explored, shedding light on how the gender of both the victim and the aggressor can influence perceptions of bullying. Another pivotal study by McCormack et al. (2018) further elucidated the dynamics of workplace bullying and highlighted the importance of gender in shaping these experiences. Their findings underscored that the dynamics of bullying become more pronounced when both the perpetrator and the target are of the same gender, revealing a worrying trend: female employees reported experiencing intimidation more frequently at the hands of other women than from male supervisors. Moreover, research has shown that intra-gender bullying—such as bullying between females or between males—occurs more frequently than instances of bullying that cross gender lines. Attell et al. (2017) posited that workplace bullying disproportionately impacts women compared to men, emphasizing a need to address this inequality. Rouse et al. (2016) conducted an extensive electronic survey aimed at uncovering gender differences in workplace bullying and identified a stark disparity: females were significantly more likely to report experiences of bullying. The findings of this body of research reveal telling patterns regarding the nature and frequency of bullying based on gender. Being female has emerged as a strong predictor of vulnerability to workplace bullying, with women reporting higher incidences of targeted harassment compared to men. The prevalence of workplace bullying among women suggests a troubling imbalance of power within professional settings, reflecting broader social inequalities. The ramifications of workplace bullying extend far beyond the immediate emotional and psychological toll; it poses serious health, social, and economic challenges for women around the world (Van De Griend & Messias, 2014). These findings highlight the critical need for awareness and intervention and the importance of fostering a culture of respect and equality at workplaces everywhere. Being a pervasive phenomenon, bullying inflicts a significant amount of physical and psychological strain on victims, which in turn may be responsible for a range of mental health concerns. The psychological symptoms manifest in the form of a general sense of disempowerment (helplessness), stress, and anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, (Tepper, 2000), low level of self-esteem (Hobman et al., 2009), impaired judgement, anger, memory loss, inability to concentrate and irritability (Appelbaum & Roy-Girard, 2007). In addition to psychological symptoms, individuals who are being bullied may also experience various physiological symptoms, including sleep disturbances, stomach issues, Numerous studies have delved into the prevalence of bullying, yet relatively few have focused specifically on intra-gender bullying, which refers to bullying that occurs between individuals of the same gender. Notably, instances of bullying perpetrated by females against other females often go unreported even though such occurrences are significant in number. Research examining the experiences of individuals subjected to bullying have revealed compelling evidences in support of women to women bullying. Admittedly, women are far more likely than males to encounter challenging behaviours at workspaces, including refusal to cooperate with them and non-collegial interactions with fellow employees. Furthermore, they often experience disrespectful, disruptive, or outright rude behaviours that their male counterparts seldom experience (Lampman, 2012). In a significant study conducted by Salin (2001), the impact of gender on workplace bullying was explored, shedding light on how the gender of both the victim and the aggressor can influence perceptions of bullying. Another pivotal study by McCormack et al. (2018) further elucidated the dynamics of workplace bullying and highlighted the importance of gender in shaping these experiences. Their findings underscored that the dynamics of bullying become more pronounced when both the perpetrator and the target are of the same gender, revealing a worrying trend: female employees reported experiencing intimidation more frequently at the hands of other women than from male supervisors. Moreover, research has shown that intra-gender bullying—such as bullying between females or between males—occurs more frequently than instances of bullying that cross gender lines. Attell et al. (2017) posited that workplace bullying disproportionately impacts women compared to men, emphasizing a need to address this inequality. Rouse et al. (2016) conducted an extensive electronic survey aimed at uncovering gender differences in workplace bullying and identified a stark disparity: females were significantly more likely to report experiences of bullying. The findings of this body of research reveal telling patterns regarding the nature and frequency of bullying based on gender. Being female has emerged as a strong predictor of vulnerability to workplace bullying, with women reporting higher incidences of targeted harassment compared to men. The prevalence of workplace bullying among women suggests a troubling imbalance of power within professional settings, reflecting broader social inequalities. The ramifications of workplace bullying extend far beyond the immediate emotional and psychological toll; it poses serious health, social, and economic challenges for women around the world (Van De Griend & Messias, 2014). These findings highlight the critical need for awareness and intervention and the importance of fostering a culture of respect and equality at workplaces everywhere. Being a pervasive phenomenon, bullying inflicts a significant amount of physical and psychological strain on victims, which in turn may be responsible for a range of mental health concerns. The psychological symptoms manifest in the form of a general sense of disempowerment (helplessness), stress, and anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, (Tepper, 2000), low level of self-esteem (Hobman et al., 2009), impaired judgement, anger, memory loss, inability to concentrate and irritability (Appelbaum & Roy-Girard, 2007). In addition to psychological symptoms, individuals who are being bullied may also experience various physiological symptoms, including sleep disturbances, stomach issues, more concealed form of women to women bullying, remains a major impediment for personal growth and productive work environment for women. Since, women to women bullying, does not manifest itself into severe forms of threat and aggression, as perceived by most people, it remains largely unaddressed by organizations. However, one cannot overlook that such disguised forms of aggressive behaviour and targeted harassment of employees by superiors or colleagues within the gender can have far reaching consequences and can be extremely detrimental to the aspirations of working women. Thus, it is important to generate awareness about this form of bullying and also devise ways to help victims cope with it. Meloni and Austin (2011) introduced a zerotolerance program for bullying and harassment in a hospital environment. After three years, the results of employee satisfaction surveys showed significant improvement. While trying to explore the correlation between psychosocial environmental factors and workplace bullying Tuckey et al. (2009) found that high job demands and low levels of social support intensified instances of bullying. The mechanism for addressing bullying is often absent in both the organized and unorganized sectors. Many women are reluctant to share their experiences of bullying due to fear of losing their jobs, while others perceive such behaviour as a normal day-to-day affair at workspace that every employee has to undergo during the course of their employment.

Numerous studies have delved into the prevalence of bullying, yet relatively few have focused specifically on intra-gender bullying, which refers to bullying that occurs between individuals of the same gender. Notably, instances of bullying perpetrated by females against other females often go unreported even though such occurrences are significant in number. Research examining the experiences of individuals subjected to bullying have revealed compelling evidences in support of women to women bullying. Admittedly, women are far more likely than males to encounter challenging behaviours at workspaces, including refusal to cooperate with them and non-collegial interactions with fellow employees. Furthermore, they often experience disrespectful, disruptive, or outright rude behaviours that their male counterparts seldom experience (Lampman, 2012). In a significant study conducted by Salin (2001), the impact of gender on workplace bullying was explored, shedding light on how the gender of both the victim and the aggressor can influence perceptions of bullying. Another pivotal study by McCormack et al. (2018) further elucidated the dynamics of workplace bullying and highlighted the importance of gender in shaping these experiences. Their findings underscored that the dynamics of bullying become more pronounced when both the perpetrator and the target are of the same gender, revealing a worrying trend: female employees reported experiencing intimidation more frequently at the hands of other women than from male supervisors. Moreover, research has shown that intra-gender bullying—such as bullying between females or between males—occurs more frequently than instances of bullying that cross gender lines. Attell et al. (2017) posited that workplace bullying disproportionately impacts women compared to men, emphasizing a need to address this inequality. Rouse et al. (2016) conducted an extensive electronic survey aimed at uncovering gender differences in workplace bullying and identified a stark disparity: females were significantly more likely to report experiences of bullying. The findings of this body of research reveal telling patterns regarding the nature and frequency of bullying based on gender. Being female has emerged as a strong predictor of vulnerability to workplace bullying, with women reporting higher incidences of targeted harassment compared to men. The prevalence of workplace bullying among women suggests a troubling imbalance of power within professional settings, reflecting broader social inequalities. The ramifications of workplace bullying extend far beyond the immediate emotional and psychological toll; it poses serious health, social, and economic challenges for women around the world (Van De Griend & Messias, 2014). These findings highlight the critical need for awareness and intervention and the importance of fostering a culture of respect and equality at workplaces everywhere. Being a pervasive phenomenon, bullying inflicts a significant amount of physical and psychological strain on victims, which in turn may be responsible for a range of mental health concerns. The psychological symptoms manifest in the form of a general sense of disempowerment (helplessness), stress, and anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, (Tepper, 2000), low level of self-esteem (Hobman et al., 2009), impaired judgement, anger, memory loss, inability to concentrate and irritability (Appelbaum & Roy-Girard, 2007). In addition to psychological symptoms, individuals who are being bullied may also experience various physiological symptoms, including sleep disturbances, stomach issues, Numerous studies have delved into the prevalence of bullying, yet relatively few have focused specifically on intra-gender bullying, which refers to bullying that occurs between individuals of the same gender. Notably, instances of bullying perpetrated by females against other females often go unreported even though such occurrences are significant in number. Research examining the experiences of individuals subjected to bullying have revealed compelling evidences in support of women to women bullying. Admittedly, women are far more likely than males to encounter challenging behaviours at workspaces, including refusal to cooperate with them and non-collegial interactions with fellow employees. Furthermore, they often experience disrespectful, disruptive, or outright rude behaviours that their male counterparts seldom experience (Lampman, 2012). In a significant study conducted by Salin (2001), the impact of gender on workplace bullying was explored, shedding light on how the gender of both the victim and the aggressor can influence perceptions of bullying. Another pivotal study by McCormack et al. (2018) further elucidated the dynamics of workplace bullying and highlighted the importance of gender in shaping these experiences. Their findings underscored that the dynamics of bullying become more pronounced when both the perpetrator and the target are of the same gender, revealing a worrying trend: female employees reported experiencing intimidation more frequently at the hands of other women than from male supervisors. Moreover, research has shown that intra-gender bullying—such as bullying between females or between males—occurs more frequently than instances of bullying that cross gender lines. Attell et al. (2017) posited that workplace bullying disproportionately impacts women compared to men, emphasizing a need to address this inequality. Rouse et al. (2016) conducted an extensive electronic survey aimed at uncovering gender differences in workplace bullying and identified a stark disparity: females were significantly more likely to report experiences of bullying. The findings of this body of research reveal telling patterns regarding the nature and frequency of bullying based on gender. Being female has emerged as a strong predictor of vulnerability to workplace bullying, with women reporting higher incidences of targeted harassment compared to men. The prevalence of workplace bullying among women suggests a troubling imbalance of power within professional settings, reflecting broader social inequalities. The ramifications of workplace bullying extend far beyond the immediate emotional and psychological toll; it poses serious health, social, and economic challenges for women around the world (Van De Griend & Messias, 2014). These findings highlight the critical need for awareness and intervention and the importance of fostering a culture of respect and equality at workplaces everywhere. Being a pervasive phenomenon, bullying inflicts a significant amount of physical and psychological strain on victims, which in turn may be responsible for a range of mental health concerns. The psychological symptoms manifest in the form of a general sense of disempowerment (helplessness), stress, and anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, (Tepper, 2000), low level of self-esteem (Hobman et al., 2009), impaired judgement, anger, memory loss, inability to concentrate and irritability (Appelbaum & Roy-Girard, 2007). In addition to psychological symptoms, individuals who are being bullied may also experience various physiological symptoms, including sleep disturbances, stomach issues, more concealed form of women to women bullying, remains a major impediment for personal growth and productive work environment for women. Since, women to women bullying, does not manifest itself into severe forms of threat and aggression, as perceived by most people, it remains largely unaddressed by organizations. However, one cannot overlook that such disguised forms of aggressive behaviour and targeted harassment of employees by superiors or colleagues within the gender can have far reaching consequences and can be extremely detrimental to the aspirations of working women. Thus, it is important to generate awareness about this form of bullying and also devise ways to help victims cope with it. Meloni and Austin (2011) introduced a zerotolerance program for bullying and harassment in a hospital environment. After three years, the results of employee satisfaction surveys showed significant improvement. While trying to explore the correlation between psychosocial environmental factors and workplace bullying Tuckey et al. (2009) found that high job demands and low levels of social support intensified instances of bullying. The mechanism for addressing bullying is often absent in both the organized and unorganized sectors. Many women are reluctant to share their experiences of bullying due to fear of losing their jobs, while others perceive such behaviour as a normal day-to-day affair at workspace that every employee has to undergo during the course of their employment.

CONCLUSION

The phenomenon of women-to-women bullying at the workspace needs to be addressed by organizations and sectors that are categorized under unorganized sectors of employment which mostly include daily wage labour, contractual services, and so on, as it has significant consequences for the women workforce. Women who target other women do so because they feel threatened and insecure owing to limited opportunities to work for women, greater challenges in finding a suitable job opportunity that fits their profile, skill set, and even family commitments. Women employees face frequent hurdles in sustaining in a male-dominated workspace, and they often end up competing with not just male colleagues but fellow female colleagues as such a hostile work environment fosters the notion of the ‘survival of the fittest’ which in turn encourages an extremely predatorial work culture. Under ideal circumstances, everyone, regardless of gender, deserves to work in a safe, respectful, healthy, and encouraging environment. Many employees who have suffered bullying, never share their experiences for fear of burning bridges or jeopardizing their future. Furthermore, in most cases, they make a calculated choice of never revisiting such a traumatic phase in their life versus career progression. This reluctance to share and report instances of bullying is often responsible for perpetuating a culture of non-collegiality between colleagues.

The phenomenon of women-to-women bullying at the workspace needs to be addressed by organizations and sectors that are categorized under unorganized sectors of employment which mostly include daily wage labour, contractual services, and so on, as it has significant consequences for the women workforce. Women who target other women do so because they feel threatened and insecure owing to limited opportunities to work for women, greater challenges in finding a suitable job opportunity that fits their profile, skill set, and even family commitments. Women employees face frequent hurdles in sustaining in a male-dominated workspace, and they often end up competing with not just male colleagues but fellow female colleagues as such a hostile work environment fosters the notion of the ‘survival of the fittest’ which in turn encourages an extremely predatorial work culture. Under ideal circumstances, everyone, regardless of gender, deserves to work in a safe, respectful, healthy, and encouraging environment. Many employees who have suffered bullying, never share their experiences for fear of burning bridges or jeopardizing their future. Furthermore, in most cases, they make a calculated choice of never revisiting such a traumatic phase in their life versus career progression. This reluctance to share and report instances of bullying is often responsible for perpetuating a culture of non-collegiality between colleagues.

SOURCE OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This study

is supported by grants from the Indian Council

of Social Science Research, Ministry of

Education, India under the major Grant

number ICSSR.RPD/MJ/2023-24/G/68 dated:

12/01/2024

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The Authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest to the Research, Authorship, and/or Publication of this article.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The Authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest to the Research, Authorship, and/or Publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Akella, D. (2016). Workplace bullying: Not a manager’s right? Sage Open, 6(1), 2158244016629394. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/2158244016629394 American Psychological Association. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder. https:/ / www.apa.org/topics/ptsd/ index.aspx Appelbaum, S. H., & Roy Girard, D. (2007). Toxins in the workplace: Affect on organizations and employees. Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society, 7(1), 17-28. Attell, B. K., Kummerow Brown, K., & Treiber, L. A. (2017). Workplace bullying, perceived job stressors, and psychological distress: Gender and race differences in the stress process. Social Science Research, 65, 210–221. h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 / j.ssresearch.2017.02.001. Bairy, K. L., Thirumalaikolundusubramanian, P., Sivagnanam, G., Saraswathi, S., Sachidananda, A., & Shalini, A. (2007). Bullying among trainee doctors in Southern India: a questionnaire study. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 53(2), 87. Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998–1012. ht t p s :/ / d oi. o rg / 10. 1037/ 0021- 9010.91.5.998. Budhwar, P. S., Varma, A., Singh, V., & Dhar, R. (2006). HRM systems of Indian call centres: an exploratory study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(5), 881- 897. Ciby, M., & Raya, R. P. (2014). Exploring Victims’ Experiences of Workplace Bullying: A Grounded Theory Approach. VIKALPA, 39(2), 69-82. Daliana, N., & Antoniou, A. S. (2018). Depression and suicidality as results of workplace bullying. Dialog Clinical Neuroscience Mental Health, 1(2), 50- 56. D’Cruz, P., & Noronha, E. (2010). Protecting My Interests: HRM and Targets’ Coping with Workplace Bullying. Qualitative Report, 15(3), 507-534. D’Cruz, P., & Rayner, C. (2013). Bullying in the Indian Workplace: A Study of the ITES-BPO Sector. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 34, 597-619. h t t p : / / d x . d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 1 7 7 / 0143831X12452672 Derks, B., Van Laar, C., & Ellemers, N. (2016). The queen bee phenomenon: Why women leaders distance themselves from junior women. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 456–469. https:// d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 / j.leaqua.2015.12.007. Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (Eds.). (2011). Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Development in theory and practice (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis. Einarsen, S. V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2020). The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In Bullying and harassment in the workplace (pp. 3- 53). CRC press. Eriksen, W., & Einarsen, S. (2004). Gender minority as a risk factor of exposure to bullying at work: The case of male assistant nurses. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13(4), 473-492. Escartín, J., Zapf, D., Arrieta, C., & RodriguezCarballeira, A. (2011). Workers’ perception of workplace bullying: A cross-cultural study. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 20(2):178-205. DOI: 10.1080/13594320903395652. Geleta, N. (2020). Workplace Bullying and Its Impact and Remedies in the 21st Century Issues. American International Journal of Social Science Research, 5(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/ 10.46281/aijssr.v5i2.513. Gholipour, A., Sanjari, S. S., Bod, M., & Kozekanan, S. F. (2011). Organizational Bullying and Women Stress in Workplace. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(6),234. https://doi.org/10.5539/ ijbm.v6n6p234. Giorgi, G., Leon-Perez, J. M., & Arenas, A. (2015). Are bullying behaviors tolerated in some cultures? Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between workplace bullying and job satisfaction among Italian workers. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(1), 227– 237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551- 014-2266-9 Harvey, c. (2018). When queen bees attack women stop advancing: recognising and addressing female bullying in the workplace. Emerald Publishing Limited,32(5),1-4. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/DLO-04-2018-0048 Hoel, H., Cooper, C. L., & Faragher, B. (2001). The experience of bullying in Great Britain: The impact of organizational status. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 443- 465. Hobman, E. V., Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2009). Abusive supervision in advising relationships: Investigating the role of social support. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 58(2), 233– 256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464- 0597.2008.00330.x Irby, C. (2019). Women bullied in the workplace. Monthly Labor Review,1- 1. Lampman, C. (2012). Women faculty at risk: US professors report on their experiences with student incivility, bullying, aggression, and sexual attention. NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education, 5(2), 184-208. Lindroth, S., & Leymann, H. (1993). Bullying Against a Minority Group of Men in Childcare: on Men’s Equality in a Women-Dominated Profession. Stockholm: Swedish National Board of Occupational Safety and Health. Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping (Vol. 464). New York: Springer. Lester, J. (2009). Not your child’s playground: Workplace bullying among community college faculty. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 33, 444–464. Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2006). Take This Job and … : Quitting and Other Forms of Resistance to Workplace Bullying. Communication Monographs, 73(4), 406–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03637750601024156. Lutgen-Sandvik, P., Dickinson, E. A., & Foss, K. A. (2012). Priming, painting, peeling, and polishing: Constructing and deconstructing the womanbullying-woman identity at work. In Gender and the dysfunctional workplace. Edward Elgar Publishing. MacIntosh, J., Wuest, J., Gray, M. M., & Cronkhite, M. (2010). Workplace bullying in health care affects the meaning of work. Qualitative Health Research, 20(8), 1128-1141. Martinek, N. (2023). Why women bully women in the workplace. Hacking Narcissism , 3(1). https:// www.hackingnarcissism.com McCormack, D., Djurkovic, N., Nsubuga-Kyobe, A., & Casimir, G. (2018). Workplace bullying: The interactive effects of the perpetrator’s gender and the target’s gender. Employee Relations, 40(2), 264-280. Meloni, M., & Austin, M. (2011). Implementation and outcomes of a zero tolerance of bullying and harassment program. Australian Health Review, 35(1), 92-94. Miner, K.N., & Eischeid, A. (2012). Observing incivility toward coworkers and negative emotions: Do gender of the target and observer matter? Sex Roles, 66, 492-505. Misawa, M., Andrews, J. L., & Jenkins, K. M. (2017). Women’s experiences of workplace bullying: A content analysis of articles between 2000 and New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development. Misawa, M., Andrews, J. L., & Jenkins, K. M. (2019). Women’s experiences of workplace bullying: A content analysis of peer reviewed journal articles between 2000 and 2017. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 31(4), 36-50. Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., … & Prisma-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMAP) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4, 1-9. Namie, G. (2017). Workplace Bullying Institute U.S. Workplace Bullying Surveys WBIZogby, Workplace Bullying Institute. In: Namie, G. (2021). Workplace Bullying Survey Report. WBI U.S. h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 3 1 4 0 / RG.2.2.14486.88647 Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2012). Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 26(4), 309–332. https:// d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 8 0 / 02678373.2012.734709 Nielsen, M. B., Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. (2011). Measuring exposure to workplace bullying. Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice, 2, 149-174. Park, J. H., Carter, M. Z., DeFrank, R. S., & Deng, Q. (2018). Abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence: The effects of gender dissimilarity between supervisors and subordinates. Journal of Business Ethics, 153, 775-792. Rouse, L. P., Gallagher-Garza, S., Gebhard, R. E., Harrison, S. L., & Wallace, L. S. (2016). Workplace bullying among family physicians: a gender-focused study. Journal of Women’s Health, 25(9), 882-888. Salin, D. (2001). Prevalence and forms of bullying among business professionals: A comparison of two different strategies for measuring bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 425-441. Salin, D. (2003). Ways of explaining workplace bullying: A review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Human relations, 56(10), 1213-1232. Salin, D. (2018). Workplace Bullying and Gender: An Overview of Empirical Findings. In: D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Caponecchia, C., Escartín, J., Salin, D., Tuckey, M. (eds) Dignity and Inclusion at Work. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment, vol 3. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-981-10-5338-2_12-1 Salin, D., & Hoel, H. (2013). Workplace bullying as a gendered phenomenon. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(3), 235-251. https:// doi.org/10.1108/02683941311321187 Sedivy-Benton, A., Strohschen, G., Cavazos, N., & Boden-McGill, C. (2015). Good ol’boys, mean girls, and tyrants: A phenomenological study of the lived experiences and survival strategies of bullied women adult educators. Adult Learning, 26(1), 35-41. Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Van Laar, C., & Levin, S. (2004). Social dominance theory: Its agenda and method. Political Psychology, 25(6), 845-880. Simpson, R., & Cohen, C. (2004). Dangerous work: The Gendered Nature of Bullying in the Context of Higher Education. Gender, Work and Organization, 11(2), 163–186. https:/ / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 1 1 1 / j . 1 4 6 8 – 0432.2004.00227. Stroup, D. F., Berlin, J. A., Morton, S. C., Olkin, I., Williamson, G. D., Rennie, D., … & Thacker, S. B. (2000). Metaanalysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Jama, 283(15), 2008-2012. Tepper, B.J. (2000). Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Academy of Management Journal,43 (2),178-190. DOI: 10.2307/1556375 Tuckey, M. R., Dollard, M. F., Hosking, P. J., & Winefield, A. H. (2009). Workplace bullying: The role of psychosocial work environment factors. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(3), 215. Van De Griend, K. M., & Messias, D. K. H. (2014). Expanding the conceptualization of workplace violence: Implications for research, policy, and practice. Sex Roles, 71, 33-42. Verkuil, B., Atasayi, S., & Molendijk, M. L. (2015). Workplace bullying and mental health: A meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS One, 10(8), 1–16. https:// d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 3 7 1 / journal.pone.0135225 Voss, M., Floderus, B., & Diderichsen, F. (2001). Physical, psychosocial, and organisational factors relative to sickness absence: a study based on Sweden Post. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(3), 178- 184. Wang, M.L., & Hsieh, Y.H. (2015). Do gender differences matter to workplace bullying? Work 53, 631–638.