Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

ASHA WORKERS IN INDIA: THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS, CONSTRAINTS,

AND PATHWAYS FOR IMPROVEMENT

Avantika Singh1 & Looke Kumari2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, 2Assistant Professor,

Department of Political Science, Bharati College, University of Delhi

Correspondence: Avantika Singh, e-mail: asingh@polscience.du.ac.in

ABSTRACT

Community Health Workers as a crucial social engineering for attaining the goal of Universal

Health Coverage has become the norm in underdeveloped and developing countries since the

early 2000s. As the goals of attaining healthcare objectives intersected with the larger goal of

achieving gender equality, the centrality of women in spearheading such initiatives was

acknowledged with great enthusiasm. This article attempts to formulate a diversified

understanding of the functions of Community Health Workers (CHW) within the context of the

Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) in India. The larger objective is to understand the unique

role of ASHA workers in contributing to India’s healthcare objectives, easing the accessibility of

marginalized masses, and assessing the associated challenges. It also highlights the agency of

ASHA in the state and the way forward to make the system more robust.

Keywords: Primary Health care, Community Health Workers, ASHAs, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

Since the welfarist development model

started gaining traction among the democratic

and socialist regimes worldwide, the idea of

delivering essential services to marginalized

social groups became prominent. The welfare

regime implies a mandate to provide social

assistance for the populace’s fundamental

sectors like health, education, employment,

and pension. The social security mandate is

one of the hallmarks of the welfare state. The

Constitution of India reflects these provisions.

India, a nation that accounts for 17% of the

global population, is responsible for 19% of

global maternal fatalities and 21% of global

juvenile deaths. Nevertheless, it has made

substantial contributions, particularly since the

introduction of the National Rural Health

Mission (NRHM) program in 2005. “NRHM

contains a variety of strategies and schemes,

such as a conditional cash transfer scheme,

an emergency transport mechanism,

i mproved communitization through the

establishment of Village Health, Sanitation,

and Nutrition Committees (VHSNC), and

investments in health infrastructure and

health workforce, which include the

establishment of a new cadre of community

health volunteers as ASHAs” (Sheila C. Vir,

2023).

National Rural Health Mission (NRHM)

It was introduced in April 2005 as an India

for Health project to enhance service quality

at the primary and secondary levels. The Ministry of Health administers this program.

The Mission aims to establish a completely

community-owned centralized healthcare

delivery system. The objective is to deliver

accessible, cheap, and accountable quality

healthcare services in rural regions. NRHM is

acknowledged as the principal initiative

encompassing all current Health and Family

Welfare programs, including “Reproductive

Child Health-2 (RCH-2), the National Malaria

Control Programme, Tuberculosis (TB), Kala

azar, Filaria, Blindness, Iodine Deficiency, and

Integrated Disease Surveillance. The Mission

is a program sponsored by Central Resources”

(Enisha Sarin et al., 2017).

The structure of the annual budget determines

the share of funding that the project would

receive. The NRHM program necessitates the

states to increase by 10% their public health

budget each year. The primary healthcare

services were extended to urban areas in

2013 when the National Urban Health Mission

(NUHM) was introduced. ASHA workers’ role

is vital in the success of such initiatives.

Hence, ASHA, the flagship extension of the

NRHM, serves as a foundational pillar for

overcoming the enduring challenges of

accessing healthcare for the rural population.

Definition of Community Health Workers

(CHWs)

They are individuals from the local community

who get monetary incentives for volunteering

to deliver health services to rural and urban

areas in tandem with the existing local system

in health care. CHWs are the first line of

defense as health professionals in the

healthcare system, with an extensive

understanding of the population they serve.

A crucial connection to healthcare systems at

the grassroots level is that they serve as an

essential bridge between the healthcare

system and their communities (Ballester,

2005). This can enhance access to healthcare

services in isolated regions.

CHWs have global recognition, originating

from community-based healthcare initiatives.

The World Health Organization, in its Alma

Ata Declaration of 1975, formally recognized

CHWs as a general designation, defining their

global role and emphasizing the critical role

of healthcare services at the primary level.

‘Health for All’ was a mission directive by the

World Health Organisation (WHO). It aims to

catalyze community development, raise

knowledge about health services and their

significance, and directly deliver healthcare.

In order to provide women in their

communities with essential and nutritional

services, CHWs are often members of the

local community who have undergone minimal

training (Walt, 1989). They usually work

intermittently as healthcare providers and are

expected to stay in their native areas.

CHWs are crucial in bridging the healthcare

system and community gap. Their

interventions are often more effective than

t hose driven solely by healthcare

professionals in identifying and leveraging the

community’s strengths to promote health

improvement (Bishop C et al., 2002). CHWs

can understand, harness, and maximize the

community’s resources, leading to enhanced

health outcomes through improved access and

cultural engagement, particularly for

underserved populations.

Despite the Indian Government’s commitment

to enhancing healthcare in rural regions

through NRHM, delivering adequate health

services remains a significant challenge. It is

crucial to recognize the need for improved

training and resources for ASHA workers at

the forefront of this Mission.

In 2002, Chhattisgarh introduced an

innovative community health care model by

appointing women as Mitanin, or Community

Health Workers. These women served as

intermediaries for marginalized groups,

bridging the gap between the needs of local

populations and distant health systems. The national government launched the Accredited

Social Health Activist (ASHA) program in

2005-06 as part of NRHM, which was later

expanded to urban areas by establishing the

National Urban Health Mission in 2013.

Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA)

NRHM in India established the ASHA program

in 2005 to enhance women’s engagement in

specialized work attendance. ASHAs are

chosen from the local community and are

committed to providing healthcare facilities.

They are instructed to link the public health

care system and the local community. The

subjects are predominantly rural women

between the ages of 25 and 45 who have

completed up to Class 10. Typically, there is

one ASHA per 1,000 individuals. This ratio may

be adjusted to one ASHA per residence in

tribal, hilly, and arid regions, contingent upon

the workload.

Joshi, R.S., and George, M. (2012), from

Thane district, Maharashtra, highlight the

diverse role of ASHA workers within the health

system as “agents of change,” encompassing

awareness, health services, family planning,

and the door-to-door dissemination of

information regarding maternity schemes and

child development programs. According to the

Policy Brief (2018), India is ranked 150th out

of 153 nations regarding women’s health and

survival, indicating poor standing. The survey

also reveals that domestic violence against

women in Western India exceeds that

experienced by 82% of males. In this context,

ASHA workers offer counseling, attentively

consider women’s circumstances, provide

guidance, and enhance their awareness,

especially when family members exhibit

conservative tendencies. Additionally, ASHA’s

primary tasks include “advocating for prenatal

and postnatal services, facilitating institutional

births, promoting regular vaccination in

children, distributing condoms and oral

contraceptive pills, and encouraging healthy

behaviors within communities” (USAID India,

2008).

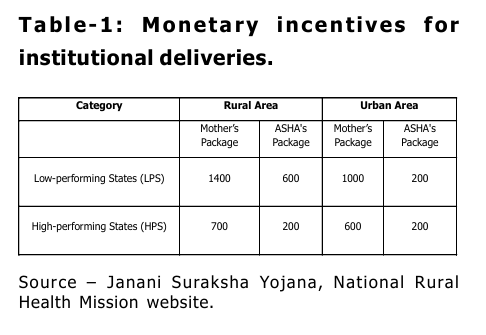

The national Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)

impacts ASHAs and new mothers significantly.

Under this mandate, most ASHAs advocate for

institutional delivery, incentivizing institutions

to deliver services. A new mother in a rural

area is entitled to Rs. 1400 and Rs. 700 in

different state settings. ASHAs receive Rs. 600

and Rs. 200 as an incentive for institutional

birth. In urban settings, a new mother is

entitled to Rs. 1000 and Rs. 600, while ASHAs

receive Rs. 200 as an incentive for institutional

birth (Table 1)

ASHA is a critical organization in the

Anganwadi community, as it promotes health

awareness, provides medical care, and

encourages community involvement. They

guide various health-related matters,

including diet, lifestyle, and work-related

circumstances. In addition, they establish a

local health plan and enable children and

expectant mothers to access medical care at

their convenience. Anganwadi officials conduct

meetings with ASHA workers, function as

reference persons for training, and provide

them with information about outreach

sessions. Additionally, they guarantee that

employees receive compensation and

participate in training. ASHA also organizes

health days at the Anganwadi Center.

The ASHA program requires ASHAs to act as

“link workers,” facilitating the connection between rural residents and health service

facilities. They serve as “service extension

workers,” providing instruction and essential

materials to encourage the preservation of

life.

ASHA workers occupy a very unique role in

making healthcare accessible to the most

marginalized and vulnerable communities.

They significantly contribute to raising

awareness on health-related issues,

mobilizing local communities for healthcare

planning, and ensuring accountability and

proper utilization of existing healthcare

infrastructure.

Their role is essential in reducing the maternal

mortality rates (MMR) in India. According to

the Sample Registration System’s (SRS) data

(2022), the mortality rate was 374 deaths per

100,000 live births from 2014 to 2016, which

declined to 97 fatalities per 100,000 live births

from 2018 to 2020.

ASHA has contributed to this significant

reduction in several ways: (a) By facilitating

hospital deliveries and providing prenatal and

postnatal care, (b) by regularly paying home

visits to pregnant women for their health

assessment and detect any possible

complications, (c) disseminating knowledge

related to women’s health and guide during

crises, (d) collaborating with governmental

programs to improve healthcare accessibility

such as Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) which

provides monetary incentives for mothers and

promotes hospital births, (e) enhancing

community spirit, addressing socio-cultural

barriers and raising awareness on health

related matters. Consequently, hospital births

in India saw a significant rise from 78.9%

(National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-4, 2015

to 16) to 88.6% (National Family Health

Survey (NFHS)-5, 2019 to 21). Moreover, the

MMR significantly decreased from 556 per

100,000 live births in 1990 to 103 per 100,000

live births in 2022.

In the same spirit, ASHA workers have also

contributed to decreasing malnutrition among

children aged five and below. The NFHS-4

(2015 – 2016) reported the malnutrition level

to be 38.4%, which was reduced to 35.5% in

NFHS-5 (2019-2021). They effectively

contribute in promoting neonatal care

practices and guiding families on the

importance of breastfeeding. This contributed

to the drastic decrease in the Infant Mortality

Rate (IMR) in India from 89 per 1000 live

births in 1990 to 27 per 1000 live births in

2022. Furthermore, ASHA workers

disseminate knowledge on the importance of

getting vaccinated and address reluctance

regarding vaccines among the populace. They

were involved in conducting door-to-door

visits, organizing village meetings, and

engaging in health campaigns to notify people

about the schedule for vaccination, especially

for children under two. They actively engaged

in the government’s flagship program, Mission

Indradhanush (2019). The objective of the

Mission was to achieve comprehensive

vaccination coverage for all children under two

years and pregnant women. ASHA workers

were equipped with digital instruments like

the MCTS to track mothers and children and

the RCH portal, where information about

vaccination coverage and schedules could be

monitored. The significant contribution of

ASHAs leads to a dramatic increment in India’s

comprehensive vaccination coverage for

children 12 to 23 months old, from 62% in

NFHS-4 (2015 to 16) to 76.4% in NFHS-5

(2019 to 21). This remarkable achievement

is accredited to the direct engagement of the

ASHA workers in ensuring that children

adhered to the prescribed vaccination

schedule, including those for diphtheria,

pertussis, tetanus (DPT), polio, measles, and

other preventable diseases. Enhanced

vaccination coverage can be directly

correlated with the reduction in child mortality

rates as reflected in the assessment of IMR, which is decreased compared to the national

average in regions where ASHA workers were

highly active, namely Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and

Himachal Pradesh.

In 2022, Kerala’s IMR was substantially lower

than the national average of 27 per 1,000 live

births, at just 6 per 1,000. In the

underprivileged districts targeted by the

Aspirational Districts Programme, where IMR

was previously high, ASHAs have played a

crucial role in enhancing healthcare delivery,

resulting in noteworthy declines in infant

mortality.

However, there has been substantial research

that has critically mapped the performance

of ASHA. Jan exhibited sub-par performance

in the immunization program, wherein the

health workers required a better

understanding of the dosages of common

medications. In a seminal work, Mahyavanshi

et al. (2011) investigated the knowledge,

attitudes, and practices of ASHA workers

related to child health in Surendranagar

district, Uttar Pradesh, revealing that 86.2%

of ASHAs possessed inadequate knowledge

about newborn care, while 90% were

unaware of the appropriate advice to provide

mothers for preventing hypothermia and

administering Kangaroo Mother Care. Seventy

percent of individuals were aware of the signs

of diarrhea, although 91.5% were uninformed

about the indications of dehydration; also,

68.46% lacked knowledge regarding measles

and pneumonia. 96.92% of ASHA staff had a

positive attitude. Furthermore, he mentioned

that although ASHAs receive training, there

i s still room for improvement in their

understanding of various aspects of childhood

illness and mortality. Therefore, enhancing

the frequency and quality of training for ASHAs

is essential.

COVID and ASHA

ASHA workers were crucial to India’s COVID

19 response, particularly in rural regions, by

doing health surveillance, contact tracing, and

public health education. Over 1 million ASHA

workers engaged in pandemic-related

activities, including door-to-door surveys and

identifying possible COVID-19 cases. They

significantly contributed to implementing

vaccination programs, which increased

vaccination rates in rural areas of India.

However, they also encountered significant

vaccine reluctance (Nair, 2024). Nevertheless,

numerous ASHAs needed to be more

adequately equipped with the appropriate

personal protective equipment (PPE).

Research indicates that 60% of them lacked

sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE)

during the early phases of the COVID outbreak

(Mishra & Rai, 2021). The workload for ASHA

employees experienced a significant increase,

and some of them worked extended hours for

minimal pay based on their success, with an

average of only INR 2,000 to 4,000 per month

(Ghosh, 2021). Despite their challenges, their

efforts to improve sanitation, implement

quarantines, and provide information

significantly reduced the virus spread in rural

spaces, highlighting their importance during

the pandemic (ibid).

The usage of ‘war’ analogies in public

discourse during the COVID-19 epidemic had

a significant impact on the perceived duties

of community health workers in India,

particularly ASHA workers. Political leaders

used war metaphors to explain the

complexities of the epidemic and encouraged

public participation by portraying COVID-19 as

an adversary that required a collective

response (Bates, 2020). These metaphors

utilized familiar concepts such as enemy,

combatant, and home spaces to support

specific policy actions and evoke a sense of

urgency, concern, and danger (Flusberg et al.,

2018). This portrayal presents healthcare

workers as “soldiers” in the fight against the

disease. As a result, they are expected to

follow the directives of their superiors and recognize that specific individuals may be

injured or required to sacrifice for the greater

good of the group (Taylor & Lohmeyer, 2020).

The political aspects of the employment of

ASHA employees were brought to light by the

COVID-19 outbreak. The government failed to

adequately address their requests, even

though they were extolled as “frontline

warriors” for administering public health at

the local level. A significant number of ASHAs

were compelled to work without adequate

personal protective equipment (PPE) and risk

pay due to the ongoing risk of long-term viral

transmission (Nanda, 2020).

However, the research indicates that the

COVID-19 epidemic has altered the role of

hope, possibly generating new chances for

individuals to reconfigure their agency and

interactions with the state. Conventional

narratives emphasize female responsibilities,

but new discourses around pandemic-related

securitization may affect the subjectivity of

community health workers in unprecedented

ways (Pfrimer & Barbosa, 2020). The public

image of impermanent workers, equal pay for

men and women, and worker rights are all

interconnected with the politics of ASHA

workers. These concerns necessitate an

examination of the future of healthcare work

within India’s political and social framework.

LIMITATION

The ASHA program has been extensively

researched since its inception; however, its

implementation could be more consistent at

the state level due to stakeholders’ varying

perspectives and notions. ASHAs must

possess comprehensive knowledge and

i mparted training for their numerous

responsibilities in various Indian contexts to

fulfill their obligations effectively. In a nation

as varied as India, it is essential to

comprehend the primary health facilities

linked to ASHAs. They need to be better

furnished with sufficient facilities. Moreover,

little and unregulated financial incentives are

provided to aspirants, which tend to dissuade

rather than encourage them (Saprii L. et al.,

2015).

CHWs have proven to be effective worldwide

in several areas related to mother and child

health, including the encouragement

to breastfeed by new mothers, timely and

proper vaccination, critical care for newborns,

health education, and reduction in IMR and

MMR (Enisha Sarin et al., 2017). Nevertheless,

challenges persist in the performance of

CHWs. Glenton C. et al. (2013) identified

organizational, social, and interpersonal

factors facilitating or impeding community

health. Although social acceptability and

organizational support were essential for

CHWs, the program’s effectiveness obstacles

were linked to the interactions between

beneficiaries and the health system, existing

socio-cultural factors, and institutional

variables (Enisha Sarin et al., 2017). The

socio-cultural norms regulating the services

of female CHWs have been deemed as

essential for the proper execution of their

duties (Khan, MH et al. 2006).

Interpersonal

barriers

encompass

interference leading to fear of blame in the

event of failure due to delays in accessing

healthcare facilities, time constraints, inability

to fulfill community needs, or a lack of

understanding. All of these may effectively

hinder the work of ASHA, who are locally

situated women and know the community well.

Additionally, ASHA workers might be a target

of community members due to Institutional

hurdles, which may encompass restricted

supplies (Low, L.K., et al. 2006), unnecessary

documentation (Javan Parsant, 2009), and

inadequate assistance from a rigid and

hierarchical healthcare system (Scott, K,

2010).

The role of ASHAs within India’s health system

and labor initiatives is deeply intertwined with

the political landscape in which they operate. Their role as informal leaders in the

healthcare domain situates them at the

crossroads of labor rights, gender politics, and

public health. The ASHA workers have

contributed significantly to the national

agenda of public health initiatives like the

National Health Mission (NHM). However, it has

been noted that the official label of

“volunteers” for the ASHA workers puts them

in a vulnerable position regarding monetary

compensation, labor rights, and societal

recognition (Scott, 2019). The official

designation of “volunteers” implies that the

monetary compensation of the ASHA workers

would be based on performance-based

incentives. The denial of a fixed salary

package and the uncertainty of receiving

regular income contributed to the widespread

dissatisfaction among the ASHA workers. It

was highlighted that their income often falls

below the subsistence level threshold,

typically between INR 2000 and 4000 per

month (Nandi & Schneider, 2020). Despite

their substantial contributions to the public

health objective and their tireless work for

public services, denying a formal work

designation excludes ASHA workers from the

protection and benefits of many social security

nets like labor laws, health insurance,

pensions, and so on.

The gendered demography of the ASHA

workforce, which is an all-women collective,

essentially implicates them within the broader

issues of gender inequality, such as the

undervaluation of care work and societal

expectations for women to undertake

caregiving roles. These narratives of

unrecognized labor necessitate them to

organize politically and meet the demands of

formalizing their work or providing adequate

financial compensation (Ved, 2019). Their

selfless contributions throughout the horrors

of the COVID pandemic justify their demands

for the formalization of work, enhanced

monetary compensation, legal contracts, and

greater inclusion in the social security

systems (Ghosh, 2021).

CHWs in underdeveloped and developing

countries are subjected to significant stress

stemming from job demands, inadequate

remuneration, poverty, gender discrimination,

and their position at the lower echelons of

systemic hierarchies. These risks are further

intensified by circumstances such as a family

member’s unemployment, children’s

education, a history of mental illness, and

marital discord. ASHAs must regulate their

emotions in response to job pressures and

interact with diverse community members and

the health system. They engage with

beneficiaries and their families in the

combined capacity of an advisor and health

care provider, potentially exhibiting a

spectrum of emotions, from elation to grief.

Knowledge, Attitude, Encouragement,

and Additional Skills of ASHA Workers:

Way Forward

Dieleman M. et al. (2003) state, ‘ to ensure

high-quality healthcare services, it is essential

t o formulate strategies that enhance

employee motivation for improved

performance.’ Research suggests that while

financial incentives are significant, they are

i nsufficient to enhance employee

performance. Various performance

management techniques may accomplish this.

Further, Dieleman M. et al. (2003) observed

in their study that acknowledgment is crucial

for healthcare worker supervisors, colleagues,

and the community. Mundhra (2010)

categorizes motivation as extrinsic and

i ntrinsic motivation. External elements

quantifiable in monetary terms, like salary and

bonuses, are defined as extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic Motivation manifests via qualities

such as interest, enjoyment, preference, and

perceived aptitude. Wichita et al. (2007)

highlight Motivation, attitude, and aptitude as

crucial for good outcomes. The socio-cultural norms regulating the services of female

Community Health Workers have been

recognized as essential for the proper

execution of their duties (Khan, M.H et al.

2006).

Franco and colleagues (2002) established a

conceptual framework for elucidating worker

motivation, which this article reflects upon.

This framework identifies internal and

external elements like self-concept, social

i nfluences, organizational systems, and

structures. Culture and community may serve

as motivating variables in assessing employee

motivation. One cannot operate in opposition

to the culture that influences one’s capacity

to execute organizational support frameworks

and fundamental procedures (Franco. LM et

al., 2002).

Further, the article bases its argument on the

NCHA’s (National Health and Advisory, 1998)

work, whose research indicated that CHWs

should possess proficient communication

abilities, instructional and presentation skills,

advocacy, organizational service coordination,

and a comprehensive understanding of the

social service system. CHW needs continuous

training and supervisory assistance to make

practical judgments during crises.

Occasionally, healthcare professionals possess

the capability to fulfill their duties but may

need more drive to exert the necessary effort

to complete all essential tasks. Worker

motivation denotes an unactualized process

that influences behavior’s direction, intensity,

and persistence (Vroom, 1996). Individual

Motivation and sufficient support from

executives and coworkers influence employee

performance (Mishra, 2014).

REFERENCES

Ballester, G. Community Health Workers:

Essential to Improving Health in

Massachusetts; A Massachusetts

Community Health Workers Survey

Report. Boston, MA: Division of

Primary Care and Health Access

Centers for Community Health,

Massachusetts Department of Public

Health, 2005.

Bates, Benjamin R. “The (In) Appropriateness

of the WAR Metaphor in Response to

SARS-CoV-2: A Rapid Analysis of

Donald J. Trump’s Rhetoric.” Frontiers

in Communication 5 (2020): 50.

Bishop, Christine, et al. “Implementing a

Natural Helper Pay Health Advisor

Program: Lessons Learned from

Unplanned Events.” Journal of Health

Promotion Practice 3, no. 2 (2002):

233–244.

Dieleman, Marjolein, Pham Viet Cuong, Le

Anh, and Tam Martineau. “Identifying

Factors for Job Motivation of Rural

Health Workers in North Viet Nam.”

Human Resource for Health 1, no. 10

(May 2003). Accessed October 18,

2024.

Flusberg, Stephen J., T. Matlock, and P. H.

Thibodeau. “War Metaphors in Public

Discourse.” Metaphor and Symbol 33,

no. 1 (2018): 1–18.

Franco, Lynne M., Sara Bennett, and Ruth

Kanfer. “Health Sector Reform and

Public Sector Health Worker

Motivation.” Social Science & Medicine

54, no. 8 (2002): 1255–1266.

Ghosh, Ananya. “India’s All-Women Frontline

Defense Against COVID-19 Fight for

Fair Pay.” Open Democracy Feature,

2021.

Glenton, Claire, Christopher J. Colvin, Bente

Carlsen, Alison Swartz, Simon Lewin,

Jane Noyes, and et al. “Barriers and

Facilitators to Implementing Lay

Health Worker Programs to Improve

Maternal and Child Health Access: A

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.”

Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews 10 (2013): CD010414.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare, Government of India.

National Family Health Survey (NFHS

5), 2019-21. Mumbai: IIPS, 2021.

Javanparast, Sepideh, John Coveney, and

Utpal Saikia. “A Qualitative Study

Explores Health Stakeholders’

Perceptions

of

Providing

Comprehensive Primary Health Care

to Address Childhood Malnutrition in

Iran.” BMC Health Services Research

9, no. 36, 2009.

Joshi, R. S., and M. George. “Healthcare

Through Community Participation:

Role of ASHAs.” Economic and Political

Weekly 47, no. 10 (2012): 70–76.

Khan, Mohammad Haroon, et al. “Assessment

of Knowledge, Attitude, and Skills of

Lady Health Workers.” Gomal Journal

of Medical Sciences 4, no. 2, 2006.

Mahyavanshi, K. D., M. G. Patel, et al. “A

Cross-Sectional Study of the

Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of

ASHA Workers Regarding Child Health

(Under Five Years of Age) in

Surendranagar District.” Healthline 7,

no. 2 (2011): 50–55.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Government of India. Mission

Indradhanush. 2019.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Government of India. National Health

Mission. 2022.

Mishra, Arima. “‘Trust and Teamwork Matter’:

Community Health Workers’

Experiences in Integrated Service

Delivery in India.” Global Public Health

9, no. 8 (2014): 960–974.

Mundhra, D. D. “Intrinsic Motivational Canvas

in the Indian Service Sector: An

Empirical Study.” The Journal of

Business Perspective 14, no. 4 (2010):

275–285.

Nair, H. V., N. Sasidharan, A. Sreedevi, et al.

“Role and Function of Frontline Health

Workers During the COVID-19

Pandemic in a Rural Health Center in

Kerala: A Qualitative Study.” Cureus

16, no. 9 (2024): e69128.

Nanda, Priya, T. N. Lewis, P. Das, and S.

Krishnan. “From the Frontlines to

Center Stage: Resilience of Frontline

Health Workers in COVID-19.” Sexual

and Reproductive Health Matters,

2020.

Nandi, Sulakshana, and Helen Schneider.

“Using an Equity-Based Framework

for Evaluating Publicly Funded Health

Insurance Programs as an Instrument

of UHC in Chhattisgarh State, India.”

Health Research Policy and Systems

18 (2020): 50.

National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4),

2015-16: International Institute for

Population Sciences (IIPS) and

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Government of India. Mumbai: IIPS,

2017.

National Rural Health Mission. Guidelines for

Community Processes. Nirman

Bhavan: Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, 2013.

Office of the Registrar General, India. Sample

Registration System (SRS) Bulletin.

Ministry of Home Affairs, Government

of India, 2022.

Pfrimer, Matheus H., and R. Barbosa. “Brazil’s

War on COVID-19: Crisis, Not

Conflict—Doctors, Not Generals.”

Dialogues in Human Geography 10, no.

2 (2020): 137–140.

Policy Brief. “The Role of Gender Bias in

Gender-Based Violence in India.”

University of Huddersfield, 2018.

Sarin, Enisha, and Sharon S. Lunsford. “How

Female Community Health Workers

Navigate Work Challenges and Why

There Are Still Gaps in Their

Performance: A Look at Female

Community Health Workers in Maternal and Child Health in Two

Indian Districts Through a Reciprocal

Determinism Framework.” Human

Resources for Health 15, no. 44, 2017.

Scott, Kerry, and Sabina Shanker. 2010. “Tying

Their Hands? Institutional Obstacles to

the Success of the ASHA Community

Health Worker Program in Rural North

India.” Aids Care – Psychological and

Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/HIV 22,

no. 12: 1606–1612.

Scott, Kerry, Abhijit S. George, and R. R. Ved.

2019. “Taking Stock of 10 Years of

Published Research on the ASHA

Programme: Examining India’s

National Community Health Worker

Programme from a Health Systems

Perspective.” Health Research Policy

and Systems 17, no. 1: 1–17.

Taylor, Nik, and Ben Lohmeyer. “War, Heroes,

and Sacrifice.” Critical Sociology,

2020.

USAID India. Accredited Social Health Activist

Plus Scheme. 2008.

Ved, R., Kerry Scott, and Abhijit S. George.

“How Are Gender Inequalities Facing

India’s One Million ASHAs Being

Addressed?” Human Resources for

Health 17, no. 1 (2019): 1–15.

Vir, Sheila C. Child, Adolescent and Woman

Nutrition in India – Public Policies,

Programmes, and Progress.

Routledge, 2023.

Vroom, Victor H. “Expectancy Model, and

Work-Related Criteria: A Meta

Analysis.” Journal of Applied

Psychology 81, no. 5, 1996.

Walt, Gill. “CHWs: Are National Programmes

in Crisis?” Health Policy & Planning 31,

no. 1 (1989): 1–21.

World Health Organisation. Declaration of

Alma Ata. 1978.

Conflict of interest: None

Role of funding source: None