Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

DIFFERENCES IN MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES UTILISATION ACROSS CASTE AND GENDER: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY FROM A TERTIARY-CARE PSYCHIATRIC INSTITUTE IN INDIA

Hariom Pachori1, Ranjan Kumar Sahoo2, B. Das3, Avinash Sharma4, Dipanjan Bhattacharjee5

1Statistician, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Kanke, Ranchi, Jharkhand , 2Associate Professor of Statistics & Head of Department, School of Statistics, Sambalpur Odisha, 3Director, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Kanke, Ranchi, Jharkhand,4Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, Jharkhand, 5Associate Professor of PSW, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Kanke, Ranchi, Jharkhand

Correspondence: Ranjan Kumar Sahoo, e-mail id: ranjansahoostatistics@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Background: The Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP), Ranchi is an apex mental health care institute situated in the Jharkhand state of the Republic of India. This institute functions under the aegis of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) and the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. In India, mental health service utilization is still not symmetrical across all sections of society. Despite significant progress in the field of public health as well as mental health many people tend to refrain from availing scientific mental health services and treatment modes. There are observable differences in utilisation of tertiary mental health services amongst people of different castes, gender and socio-economic backgrounds. Aim: To see the differences in mental health services utilisation across caste and gender. Method: This study was retrospective in nature. This study was based on a retrospective analysis of routinely recorded patients’ related clinical data collected during 2012 and 2017. Conclusion: In the present study, it was noted that, within the span of 05 years, there was more than 19.68% increase in patients’ registration at OPD level. In the present study, it was noted that, in case of new as well as follow-up cases, males have always constituted an overwhelming majority. In the context of new cases (patients coming to the Institute for the first time), the number of male patients almost doubled during 2012 to 2017 and at the time of follow-up, this difference was seen to have further increased by nearly 2½ times.

Keywords: Mental Health, Gender difference, Services utilisation.

INTRODUCTION

Tertiary care is understood as specialised intervention delivered by highly trained staff to individuals with problems that are complex and refractory to primary and secondary care. Usually, this type of care is initiated through referrals from secondary care. Criteria for tertiary care include: ‘presence of higher levels of management and security’, ‘higher expertise of the staff’, and ‘higher availability of staff and resources’, as well as ‘provisions of more detailed and specialized assessment and treatment services for the patients’ (Wasylenki et al., 2000). Tertiary care has emerged as a pivotal factor in providing universal access to healthcare in the 21st century. Although theoretically tertiary care is required for those cases with a high degree of complications and refractoriness that are unable to be dealt with by the primary or secondary healthcare systems, however, in a country like India, many-a-time tertiary mental health establishments are seen to take extra load of patients due to unavailability of trained manpower at primary and secondary levels (Zachariah, 2012). In low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) very few mentally ill people receive mental health care at the primary care level. As primary mental health services in India are still somewhat under-developed, therefore, existing tertiary governmental mental health establishments end up addressing the mental health needs of a large section of population. However, many of the patients could be treated at the primary level itself as their mental health conditions does not warrant specialized treatment from tertiary centres (World Health Organization, 2008; Patel & Thornicroft, 2009). This study is an endeavour to see the pattern of patient turnover in a tertiary mental health facility located in the Eastern Region of the Republic of India. This study was carried out at the Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP), which has been operating under the aegis of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The Institute is located in the city of Ranchi, the capital of the province Jharkhand, India. This Institute was established in 1918 by the British Indian Government to cater to the mental health needs of British and European civilians working and residing in India. Till India gained independence from the British in 1947, care at this Institute was restricted to those of British and European stock while Indians themselves were excluded. When it was established, the Institute went by the name of ‘Ranchi European Lunatic Asylum’ and all Europeans and Anglo-Indian inmates of the Bhowanipore and Berhampore Lunatic Asylums were transferred to this Institute. On October 27, 1919 Lt. Colonel Owen Berkeley-Hill, a psychiatrist in the British Army took over the post of Medical Superintendent of the Ranchi European Lunatic Asylum. As a result of his efforts, the tag of ‘lunatic asylum’ was removed and it was termed as ‘mental hospital’ in 1920 (Nizamie et al., 2008). Since independence, India has achieved several milestones in the areas of science and technology, industry, education, finance and economy and health. However, the quality of development of public mental healthcare system has not occurred uniformly in the country. Some parts of the country have a reasonably better mental healthcare system operating in the form of effective primary and referral mental healthcare systems and existence of a good synergistic relationship among various quarters of public mental health system and administration. Regrettably, a large part of the country still does not have a well-functioning public mental health system. Therefore, the workload of tertiary centres like CIP has soared up quite significantly in recent years. The National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) of India was announced nearly four decades ago in 1982, as an integrated and comprehensive mental healthcare approach to meet the mental health needs of common people. However, the success of this programme has not been seen uniformly in all regions and parts of the country. CIP has been serving the mental health needs of the people of several states including Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, eastern and north-eastern parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh as well as a neighbouring country Nepal. Despite limitations in manpower and other resources the Institute has been performing reasonably well in serving the needs of the community, which have risen significantly year-on-year. Past community-based epidemiological studies on mental and behavioural disorders showed varying prevalence rates in India, ranging from 9.5 to 102/1000 population (Math & Srinivasaraju, 2010). As per the Report of the National Sample Survey Organization (2002), overall population prevalence of mental illness was 14.9/1000, which was found to be higher in rural areas (17.1/1000) than urbanized areas (12.7/ 1000) (Lakhan & Ekúndayò, 2015). Between 1990 and 2013, the estimated burden of mental disorders in India increased by 44% along with neurological and substance use disorders and it is expected to increase further by 23% in India between 2013 and 2025 (Charlson et al., 2016; Haldar et al., 2017).

AIM

To see the differences in mental health services utilization across caste and gender.

MATERIALS & METHODS

This study is retrospective in nature and the annual statistical data related to patient-care and mental health services provided by the Institute was used in the study. Last five years data related to the services were used in the present study. The Computer Section of the Institute maintains the database of the Institute. Instructional data on various aspects related to patient-care, services and illness during the span of 2012-2017 are included in the study. This study is based on a retrospective analysis of routinely recorded patient related clinical data collected between 2012 and 2017 at the institute. The data were abstracted in Microsoft Excel and descriptive analysis was done for enumerating the number and percentages of the various parameters/variables. Patient related as well as clinical data of two specific years, i.e., 2012 and 2017 were compared for understanding the trends in last five years.

RESULTS

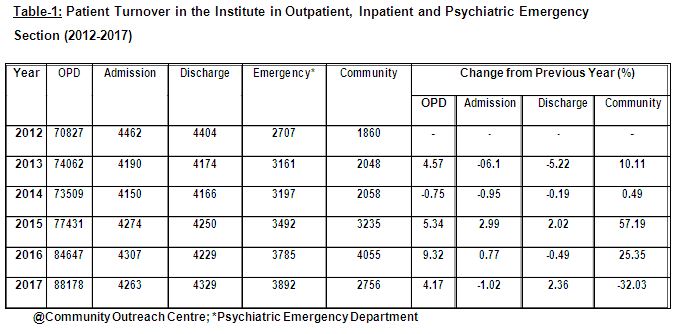

Table 1 depicts the patients’ turnover during the span of five years (2012-2017) at CIP, Ranchi. From this table, important year-wise statistics like ‘Total number of registrations at the Outpatient Department (OPD)’, ‘Number of patients admitted and discharged from the Inpatient Units’, ‘Number of registrations at the Psychiatric Emergency Department’, ‘Number of people availing mental health services from the Community Outreach Clinics of the Institute’ and most importantly rate of changes occurring in each year in each of these variables from preceding year’ can be seen.

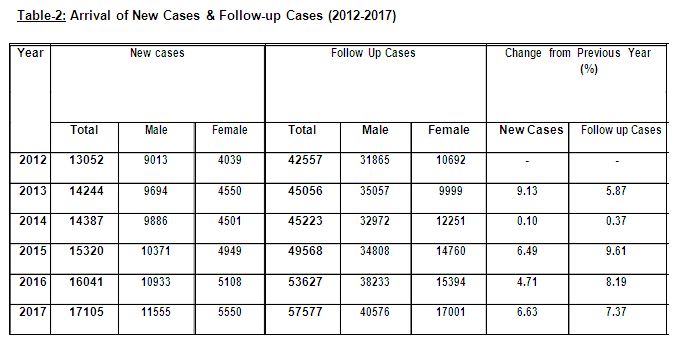

Table 2 shows the five-year (2012-2017) statistics on arrival of new patients in the OPD of the Institute for seeking treatment for their psychological problems. The table also shows the number of follow-up cases seen at the Institute during the same time-frame. A steady increase can be seen with respect to arrival of new cases (people who came to the Institute for the first time). This table also depicts the gender-wise break-up of both new-cases as well as follow-up. Cases males outnumbered the females each year both in terms of new cases and follow-ups. With the exception of the one year period 2013-2014, when the rate of change in both new cases and follow-up cases was found to be rather meagre (0.10% and 0.37% respectively), steady increase was seen at the end of each year under study.

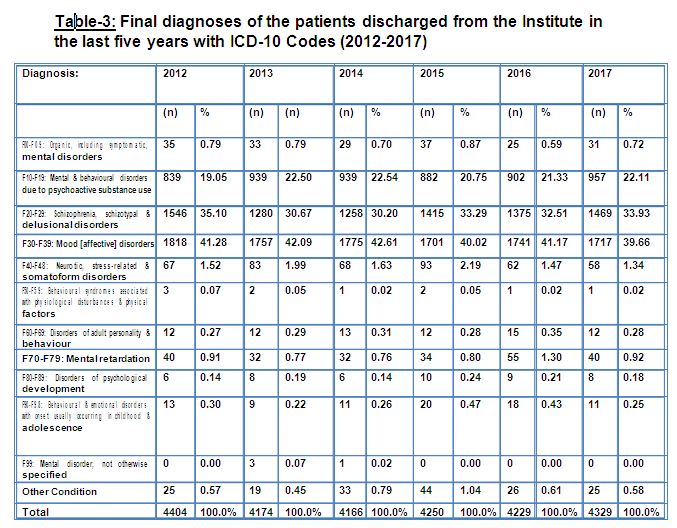

Table 3 depicts the final diagnoses of patients at the time of their discharge. In terms of final diagnoses, a consistent result can be seen. Diagnoses were made using the ICD-10 criteria (WHO, 1993) and in each year between 2012-2017, patients meeting the criteria of Mood [affective] disorders (F30-F39) have been in majority; this diagnosis is followed by the patients with Schizophrenia, schizotypal & delusional disorders (F20-F29). The diagnosis of psychoactive substance dependence (ICD-10-DCR Criteria F10-F19: Mental & behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use) was seen to be consistently at the third position. Least number of cases was found in two criteria, i.e., ‘F50-F59: Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances & physical factors’ and ‘F99: Mental disorder, not otherwise specified’. Cases fulfilling the criteria of ‘F00-F09: Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders’, ‘F40-F48: Neurotic, stress-related & somatoform disorders’, ‘F60-F69: Disorders of adult personality & behaviour’ and ‘F70-F79: Mental retardation’ were fewer in comparison. It should be noted that these statistics were related to admitted cases.

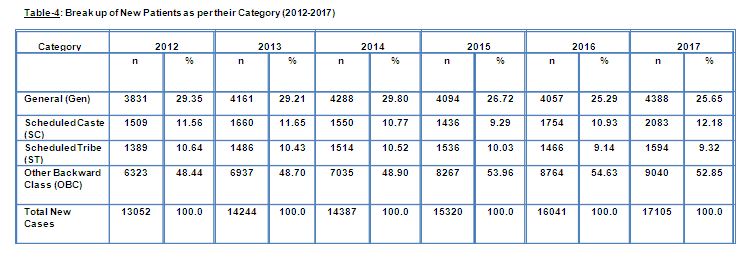

Table 4 shows the breakup of new cases that got registered during 2012-2017 as per their category. In terms of category, for each year under study, almost similar results were observed. Majority of the cases were from the Other Backward Class (OBC) Category which was followed by General Category. Except for the year 2015, people belonging to the Scheduled Caste Category came in third position (in the year 2015 patients from the ST Category outnumbered those from the SC Category).

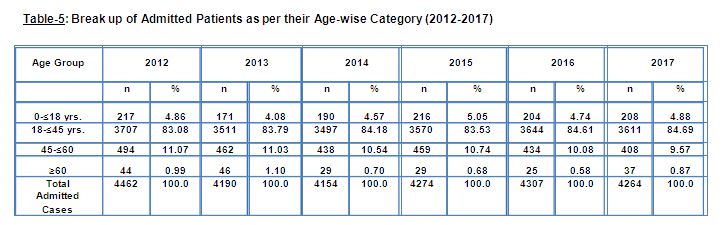

Table 5 depicts the age profile of discharged patients. Here, consistency can be seen in the form of overwhelming majority in admission of patients belonging to the ‘age group of 18-45 yrs.’ Patients aged 60 year and above can be seen to be least represented in the inpatient wards of the Institute. People belonging to the age group of 45-60 years come in second position in terms of number of admission in the inpatient wards. The number of admissions of minors as inpatients has always followed the above mentioned groups in terms of numbers.

DISCUSSION

This study was carried out at CIP, Ranchi, a referral and tertiary mental healthcare institute situated in the city of Ranchi, the capital of the state of Jharkhand. This Institute has been the apex mental healthcare institute in this part of the country for the last century. Tertiary care is understood to be the specialised consultative health care services which are usually provided to people after being referred by healthcare professionals working at the primary or secondary healthcare levels. Tertiary institutions are those which have both the manpower and other physical/infrastructural facilities to cater to the complicated health needs of people. Tertiary institutes are recognized for their highly skilled and professional workers and ability to provide quality services. Tertiary care should be made available to people having complicated health issues and people with minor or moderate health problems should be catered to at the primary and secondary care levels. In an integrated and synchronized healthcare system, patients are expected to receive care at the primary and secondary level for most conditions, and some cases which are more complex in terms of aetiology, management and aftercare are referred for more specialized tertiary care. However, in order to follow this thumb-rule, the healthcare system requires strong and effective primary and secondary systems of health-care. In India both the primary and secondary healthcare systems have certain intricate insufficiencies, therefore, tertiary systems are found to be often catering to the needs of minor health issues, which could have been dealt effectively at the primary or at most, the secondary care level. In case of mental health this is seen even more starkly. There continues to be a surge in the number of mentally ill individuals in the community and as we know in India, there is a serious dearth of mental health professionals and institutes to cater to the mental health related needs of the people. Primary mental health care has not yet developed uniformly across the country. Therefore, people tend to rely on tertiary care for seeking help for their psychological problems. This phenomenon has been reflected in the statistics of this Institute too. In the year 2012, 70827 people got themselves registered at this Institute for seeking treatment, which increased to 88178 in 2017, an increase of 19.68%. This seems to be significant increase in the span of 05 years. This can be attributed to myriad factors, e.g., ‘increase in mentally ill individuals in the population’, ‘increase in awareness level about mental illnesses’ and ‘lack of availability of mental health-care services at primary level’. This Institute is not the only example of a tertiary healthcare institute in the country where patient-burden has increased – even super-specialty institutions like All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER), National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) have also been facing high burden of patients who could have been treated appropriately at primary or secondary levels (Working Group on Tertiary Care Institutions). It is a matter of concern that mentally ill patients have to travel from far-flung or remote areas for seeking help at tertiary institutions like CIP. The demand of specialized mental health services of this Institute has been increasing consistently in last decade, barring one or two occasions where number of registrations have decreased. However, that seems to be momentary and exceptional in nature as the number regained its ‘growing tendency’ in subsequent years. The numbers of admissions and discharges from the inpatient wards of the Institute have also been found to be increasing as per the increase of OPD Registration. In the present study, it was noted that, within the span of 05 years, there was more than 19.68% increase in patients’ registration at OPD level (Table-1). This might be attributed to various factors or variables, e.g. ‘significant increase in sharing of mental, neurological, and substance use in the global burden of disease’ (WHO, 2004; Haldar et al., 2017), ‘considerable increase of people with mental, neurological and substance use (Patel et al., 2016)’, ‘lack of availability and accessibility of specialized and basic mental health services at primary and secondary levels in this part of the country’, ‘growing awareness about mental illness’, etc. In the present study, it was noted that, in case of new as well as follow-up cases, males have always constituted an overwhelming majority (Table 2). In the context of new cases (patients coming to the Institute for the first time), the number of male patients almost doubled during 2012 to 2017 and at the time of follow-up, this difference was seen to further increase to nearly 2½ times (Table-2). This suggests that females do not avail treatment for their mental illnesses at the tertiary level as much as males, neither do they come for regular follow-ups. This might be attributed to various illness related as well as socio-cultural factors, e.g. ‘possible impact of gender on age of onset of symptoms, clinical features, frequency of psychotic symptoms, course, social adjustment, and long-term outcome of severe mental disorders’, ‘social interpretation, attribution and acceptance of mental illness in women’, ‘forms of social support available and accessible to women with mental illnesses’ and most importantly ‘anticipating societal rejection in the forms of stigma, stereotypes and prejudices for mentally ill women and their caregivers’ (Malhotra & Shah, 2015). In terms of availing the mental health facilities, studies have shown a ratio of one woman for every three men attending public health psychiatric outpatient facilities in urban India. This clearly points to “under-utilization” of services by suffering women. There is likely greater stigma attached to women’s mental illness that negatively impacts the help-seeking behaviour for public mental health facilities and/or lesser importance is given to mental health issues pertaining to women in general. Gender can escalate the discrepancy between prevalence and utilization. This low attendance can also be explained by the lack of availability of specific resources meeting women’s needs appropriately at the hospital settings. Most mental hospitals seem to preferentially allocate health facilities to males as can be seen in the sex-based discrepancy in the availability of beds. The male:female ratio for the allotment of beds in government mental health-care facilities is 73%:27% while those with service, research, and training is 66%:34% (Davar, 1999; Sood, 2008; Malhotra & Shah, 2015). This way, predominance of males in utilization of services, which was observed in the present study, is consistent with previous observations. In relation to diagnoses of discharged patients of the last five years under study (2012-2017), a preponderance of mainly three types of diagnoses was found viz., ‘Mood [affective] disorders (F30-F39)’, ‘Schizophrenia, schizotypal & delusional disorders (F20-F29)’ and ‘Mental & behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10-F19)’, with ‘Mood Disorders’ being the most common diagnosis, followed by Schizophrenia, schizotypal & delusional disorders’ and ‘Mental & behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use’ (Table-3). This can be attributed to the very nature of the Institute, this Institute being a tertiary or referral one, hence people with severe mental disorders like the three mentioned above tend to come here to receive intensive treatment. Another possible reason could be that people with other psychiatric diagnoses do not opt for admission into inpatient wards and rather prefer to take treatment at the OPD level. In terms of age and category of the admitted patients in the last five years (2012-2017), almost similar pattern was noted, i.e., preponderance of people belonging to the age group of 18-45 years and Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. The preponderance of age-group can be attributed to a higher prevalence and incidence of severe and common mental disorders in this age group in keeping with several past epidemiological studies that have shown categorically that people in this age-group are mostly affected by mental disorders (Verghese et al., 1985; Fenton & McGlashan, 1991; Thara, Padmavati & Nagaswami, 1993; Wig et al., 1993; Kulhara, Shah & Aarya, 2010; Rao, 2010; Baxter et al., 2016; Murthy, 2017). As per the survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), the OBCs constitute 40.94% of the population, the SC population is 19.59%, the ST population is 8.63% while the rest constitute 30.80%. Therefore, the preponderance of persons belonging to the OBC Category in the discharged list can be explained by the demographics of the population.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, it was noted that, within the span of 05 years, there is more than 19.68% increase in patients’ registration at OPD level. In the present study, it was noted that, in case of new as well as follow-up cases males have always constituted an overwhelming majority than females. In the context of new cases (patients coming to the Institute for the first time), the number of male patients almost doubled during 2012 to 2017 and at the time of follow-up, this difference was seen to further increase to nearly 2½ times.

REFERENCES

Baxter, A.J., Charlson, F.J., Cheng, H.G., Shidhaye, R., Ferrari, A.J., & Whiteford, H.A. (2016). Prevalence of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: A systematic analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3, 832 – 841. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30139-0

Charlson, F.J., Baxter, A.J., Cheng, H.G., Shidhaye, R., & Whiteford, H.A. (2016). The burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: A systematic analysis of community representative epidemiological studies. The Lancet, 388, 376-389.

Davar, B.V. (1999). Mental Health of Indian Women– A Feminist Agenda. New Delhi/ Thousand Oaks/London: Sage Publications.

Fenton, W.S., & McGlashan, T.H. (1991). Natural History of Schizophrenia Subtypes-II. Positive and Negative Symptoms and Long-term Course. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 978–986. doi:10.1001/ archpsyc.1991.01810350018003

Haldar, P., Sagar, R., Malhotra, S., & Kant, S. (2017). Burden of psychiatric morbidity among attendees of a secondary level hospital in Northern India: Implications for integration of mental health care at subdistrict level. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 59, 176-182. doi: [10.4103/ psychiatry. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 324,16.

Kulhara, P., Shah, R., & Aarya, K.R. (2010). An overview of Indian research in schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, S159-S172. doi: [10.4103/0019-5545.69229]

Lakhan, R., & Ekúndayò, O.T. (2015). National sample survey organization survey report: An estimation of prevalence of mental illness and its association with age in India. Journal of Neuroscience in Rural Practice, 6, 51-54. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.143194.

Malhotra, S., & Shah, R. (2015). Women and mental health in India: An overview. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 57, S205-S211. doi: [10.4103/0019-5545.161479].

Math, S.B., & Srinivasaraju, R. (2010). Indian Psychiatric epidemiological studies:

Learning from the past. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, S95-S103.

Murthy, R.S. (2017). National mental health survey of India 2015–2016. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 59, 21-26

Nizamie, S.H., Goyal, N., Haq, M.Z., & Akhtar, S. (2008). Central Institute of Psychiatry: A tradition in excellence. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 144-148. doi: 10.4103/ 0019-5545.42405.

Patel, V., & Thornicroft, G. (2009). Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low-and middle-income countries: PLoS Medicine Series. PLoS medicine, 6, e1000160. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-30

Patel, V., Chisholm, D., Parikh, R., Charlson, F.J., Degenhardt, L., Dua, T., Ferrari, A.J., Hyman, S., Laxminarayan, R., Levin, C., Lund, C., Medina Mora, M.E., Petersen, I., Scott, J., Shidhaye, R., Vijayakumar, L., Thornicroft, G., & Whiteford, H., DCP MNS Author Group (2016). Addressing the

burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: Key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. The Lancet, 387, 1672-1685.

Rao, P.G. (2010). An overview of Indian research in bipolar mood disorder. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, S173-S177. doi: [10.4103/0019-5545.69230].

Report of the Working Group on Tertiary Care Institutions for 12th Five Year Plan (2012-2017). No. 2 (6)2010-H&FW, Government of India, Planning Commission. Downloaded from: http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/c o m m i t t e e / w r k g r p 1 2 / h e a l t h /WG_2tertiary.pdf

Sood, A. (2008). Women’s Pathways to Mental Health in India. UC Los Angeles: UCLA Center for the Study of Women. 2008. Downloaded from: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/0nd580×9.

Thara, R., Padmavati, R. & Nagaswami, V. (1993). Schizophrenia in India. Epidemiology, Phenomenology, Course and Outcome,International Review of Psychiatry, 5, 157-164, DOI: 10.3109/09540269309028306

Verghese, A., Dube, K.C., John, J., Menon, D.K., Menon, M.S., Rajkumar, S., Richard, J., Sethi, B.B., Trivedi, J.K., & Wig, N.N. (1985). Factors associated with the course and outcome of schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 27, 201-206.

Wasylenki, D., Goering, P., Cochrane, J., Durbin, J., Rogers, J., & Prendergast, P. (2000). Tertiary mental health services: I. Key concepts. Canadian Journal Psychiatry, 45, 179-184. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/ 070674370004500209

Wig, N.N., Varma, V.K., Mattoo, S.K., Behere, P.B., Phookan, H.R., Misra, A.K., Murthy, R.S., Tripathi, B.M., Menon, D.K., Khandelawal, S.K., & Bedi, H. (1993). An incidence study of schizophrenia in India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 35(1), 11-17.

World Health Organization (2004). The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press.

World Health Organization (2008). mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: Scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders.

Zachariah, A. (2012). Tertiary Healthcare within a Universal System: Some Reflections. Economic & Political Weekly, 12, 39-45.

Conflict of interest: None

Role of funding source: None

Производитель спецодежды в Москве сапоги эва мужские

– купить оптом спецодежду.