Background: Menstruation is considered a universal experience, but transition-aged youth in

tribal communities often remain critically underinformed about menstrual hygiene. The pervasive

influence of cultural taboos and misinformation, coupled with inadequate access to essential

facilities and sanitary products, exacerbates health risks and emotional distress. Aim: This study

aimed to explore menstrual knowledge, attitudes, and practices among transitioned-aged young

women in the Siddi tribe. Methods and Materials: The study employed an exploratory design

with purposive sampling of 32 participants from the Siddi tribal community in Yellapur Taluka,

Karnataka. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and analyzed thematically to

uncover key themes. Results: Thematic analysis yielded four principal themes: access to

menstrual hygiene products, hygiene practices, privacy and facilitation, stigma and myths, health

and wellbeing, and menstrual knowledge and awareness. Within these overarching themes, several

sub-themes were accentuated, supported by direct verbatims from the interviews, providing

nuanced insights into the participants’ experiences. Conclusion: The study revealed low

menstruation-related knowledge among Siddi tribal women, with menarche typically starting at

age 14. Early marriage is common, with 62.5% of transitioned-aged women already married,

contrasting with other tribes where marriage often occurs later. Many women have poor

understanding of menstruation, relying on misinformation from friends and family, which contributes to health issues. Menstruation remains taboo, influenced by cultural and religious

factors, with common rituals and inadequate hygiene practices. Many women use reusable clothes

under poor conditions, raising health risks. These findings emphasize the need for targeted

interventions to enhance menstrual health education, accessibility, and cultural sensitivity within

the Siddi community, fostering improved psychological well-being.

Transition-aged youth (15-29 years) confront

several transitional challenges (Dar &

Sobhana, 2024). This transitional period is

marked by menarche, a significant milestone

often surrounded by traditions, myths, and

misconceptions within Indian culture.

Menstruation is a fundamental aspect of a

woman’s life, perceived differently across

various social and cultural landscapes.

Despite being a routine biological function, it

continues to be cloaked in stigma, taboos, and

secrecy (Mudi et al., 2023). Pervasive myths,

such as the prohibition of entering religious

spaces, designate women as impure, leading

to their exclusion from worship and imposition

of various domestic restrictions, including

cooking and handling certain foods. These

taboos, seldom confronted in public or private

discourse, foster misconceptions and

insufficient menstrual preparedness. The

consequent psychological distress and societal

constraints on daily life are acutely observed

in rural and tribal areas, notwithstanding

gradual changes among urban, educated

populations (Upashe et al., 2015). The

insufficient management of menstrual hygiene

(MHM) is a global issue, particularly in low

and middle-income countries, where

individuals frequently lack the requisite

knowledge, confidence, and skills to manage

their menstrual health effectively. (Garg &

Anand, 2015). Maintaining MHM is vital for the

health and dignity of menstruating women.

Effective MHM requires access to basic

amenities, including clean absorbent

materials, water, soap, and private sanitation

facilities. The selection and proper use of

menstrual absorbents are crucial, as

inadequate MHM can lead to serious health

issues, such as genital and urinary tract

i nfections. As per the World Health

Organization (WHO), 1.7 billion people

globally lack access to basic sanitation,

compelling many women to resort to

unsanitary materials due to insufficient

awareness and the high cost of menstrual

products. (WHO, 2023). A study carried out

in Odisha found a strong association between

the increased occurrence of reproductive tract

infections (RTIs) and poor menstrual hygiene,

emphasizing the broader health and economic

consequences. (Torondel et al., 2018). Open

communication about menstrual hygiene

management (MHM) is vital, as inadequate

MHM hinders the progress of several

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),

particularly those related to gender equality,

education, and economic participation.

Understanding and improving MHM is essential

not only for individual well-being but also for

t he advancement of broader societal

objectives. Despite its significance, menstrual

hygiene remains a neglected issue, requiring

greater attention and action to ensure

women’s health, empowerment, and overall

societal progress.

In India, social group affiliation critically

i nfluences access to resources, with

marginalised groups such as Scheduled

Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) consistently lagging in socioeconomic

development and health outcomes (Ram et al.,

2020). These communities often lack essential

information on safeguarding women’s health

during

menstruation, leading to

disproportionate susceptibility to preventable

reproductive health issues and limited

knowledge of hygienic practices. Research in

Odisha’s tribal districts found that over one

third of adolescent girls use unsanitary

materials as menstrual absorbents, with cloth

remaining a preferred choice due to its

availability and low cost (Mishra, 2020).

Significant disparities in menstrual hygiene

practices are apparent, as indicated by the

National Family Health Survey (2019–21),

which shows that 59% of tribal women aged

15–24 use cloth, compared to just 25% of

women from the general castes (Ram et al.,

2020).

A recent analysis of nationally representative

survey data on menstrual hygiene

management in India reveals troubling trends.

Fewer than 40% of transitioned-aged (15

24years) women use disposable absorbents

exclusively, with most relying on reusable

materials such as clothes, which can increase

health risks (Ram et al., 2020). The study

reveals significant disparities driven by

personal, family, and community factors. In

rural and non-southern regions of India, as

well as among women with lower

socioeconomic status, less education, and

those from tribal and minority communities,

the use of disposable absorbents is notably

infrequent.

The higher use of disposable absorbents in

southern states is attributed to better

resources, infrastructure, and higher female

literacy. For example, Tamil Nadu schools

provide separate toilet and menstrual waste

disposal facilities, unlike those in Maharashtra

and Chhattisgarh (Sivakami et al., 2019).

Rural women have less menstrual hygiene

knowledge compared to their urban peers,

impacting their practices. Findings of the study

revealed that there is more frequent

commercial pad usage in urban areas and

continued reliance on clothes in rural and

tribal regions.

Ram et al., in 2020, reported a particularly

low rate of exclusive disposable absorbent use

among young women from Scheduled Tribes,

with less than a quarter using them compared

to nearly half from general castes. Caste

identity remains a significant factor in social

inclusion and access to resources. Despite

policies aimed at improving conditions for

lower-caste individuals, the study emphasizes

the need to prioritise menstrual hygiene within

these efforts. Kumar and his associate have

identified a substantial gap in menstrual

knowledge and management among tribal

women, influenced by access, financial

constraints, and cultural practices (Kumar &

Srivastava, 2011).

This primary objective was to explore the

cultural context of menstruation in the Siddi

tribal community and address cultural nuances

and unique challenges to develop culturally

i nformed interventions and education

initiatives that enhance menstrual hygiene and

community well-being. The study underscores

the crucial role of education, economic status,

and regional influences in shaping menstrual

hygiene practices.

Data for this qualitative study were collected

through interviews and analyzed thematically.

The iterative theme analysis method—

comprising grouping, coding, identifying,

assessing, defining, and reporting themes and

sub-themes—transformed unstructured data

into meaningful insights (Clarke & Braun,

2017). This approach allowed for the

extraction of significant themes by identifying

patterns within the data. Purposeful sampling selected a total of 32 participants, as detailed

in Table 1. The limited sample size can be

attributed to the isolated nature of the tribal

community, where each participant lived

approximately ten kilometers apart in the

forest.

Eligibility for participation required

membership in the Siddi tribal community,

willingness to participate, and effective

communication skills. Participants were

provided with comprehensive information

about the study before the interviews, and

mutually convenient times were arranged.

Additionally, demographic data, including age,

gender, and religion, were collected from the

participants. This study was conducted with

t ransitional-aged women residing in

underprivileged areas of Yellapur Taluk,

Karwar district, Karnataka, India, from

October 28 to November 6, 2023. It was part

of the curriculum for the Honour’s Bachelor’s

program in Public Health and Masters Social

Work at the Karnataka State Rural

Development and Panchayat Raj University.

The Social Work Department organized a ten

day Tribal Camp (RDPRU/02/PHSW/2021) as

part of the curriculum, which provided insights

into the health, customs, and culture of the

Siddi tribal community, with a particular

emphasis on menstrual hygiene. Data

collection was collected by four female

researchers, with each interview lasting a

minimum of one hour and thirty minutes. A

total of 32 participants were selected through

purposive sampling. The right to privacy for

participants was rigorously maintained

throughout the study. Interviews were

conducted in confidential settings without the

presence of any additional individuals.

Participation was entirely voluntary, with

minimal risks involved, and all information

shared was ensured to be kept confidential

by providing participatory information (PI)

forms and consent information sheets (CIS)

detailing ethical considerations, including

informed consent, confidentiality, and privacy,

given the sensitive nature of the topic. These

measures ensured that participants

understood their rights and the protections for

their personal information.

Prior to data collection, the researchers

undertook an extensive review of menstrual

hygiene practices among tribal communities,

with a specific focus on the Siddi tribe due to

their comparatively low educational status.

The four researchers were trained for data

collection procedures, including the

administration of semi-structured interviews

prior to data collection. The right to privacy

for participants was rigorously maintained

throughout the study. Interviews were

conducted in confidential settings without the

presence of any additional individuals.

Participants were given consent forms and

information sheets detailing the study. The

confidentiality of their personal identities was

assured.

The interview guide, developed through a

comprehensive literature review and

translated into the local language Kannada by

a specialized translator, included questions

such as: “Can you describe what menstruation

is and how you learned about it?”, “What

sources of information or education about

menstruation are available to you in your

community?”, “Do you have access to clean

and private facilities for changing and

disposal?”, and “Have you encountered any

myths or taboos related to menstruation, and

how do they affect your daily life?” Additional

prompts were used to elicit further

clarification. The interviews were audio

recorded and transcribed, with an average

duration of two hours.

Data analysis included interviews with all 32

participants. For participants who

communicated in Kannada, the researcher

translated the audio-recorded transcriptions

i nto English. The following steps were

employed to analyse the data using thematic analysis:

1. Thoroughly read the transcripts to ensure

a comprehensive understanding of the

details.

2. Developed codes based on identified

commonalities.

3. Identified all potential themes and sub

themes.

4. Reviewed the identified themes to ensure

they accurately represent the dataset.

5. Label the themes with clear and precise

descriptions.

6. Articulated the narratives derived from the

data analysis in a clear and compelling

manner in the final report (Clarke & Braun,

2017).

Before analysis, all information collection

involved field notes, observations, reflections,

interviews, and audio or visual recordings.

Interviews were transcribed to create textual

data for analysis. NVivo software was used

for data management, coding, and theme

generation.

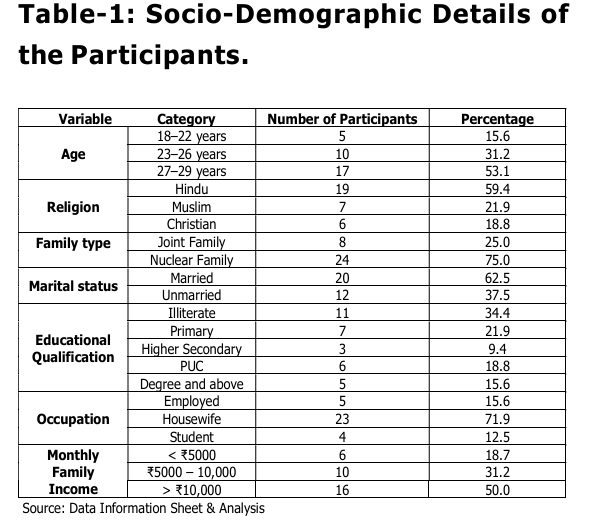

Table-1: provides the socio-demographic

characteristics of the 32 participants. The

majority of participants (53.13%) were late

youth, aged 27-29, while 31.25% were

emerging youth, aged 23-26, and the

remaining 15.63% were early-aged youth (18

22 years). Most participants identified as

Hindu (59.4%), followed by Muslim (21.9%)

and Christian (18.8%). The majority lived in

nuclear families (75%) and were married

(62.5%). Notably, a significant number

(34.4%) were illiterate, indicating potential

barriers to accessing information on menstrual

health. Occupation-wise, most participants

were housewives (71.9%), and the majority

had a monthly family income greater than ¹

10,000 (50.0%)

The analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s

(2006) six-phase framework for thematic

analysis, ensuring a rigorous approach to

identifying, coding, and validating key themes

from the data (Nowell et al., 2017; Clarke &

Braun, 2017). The interview transcripts were

read and re-read to familiarize researchers

with the content, noting recurring concepts.

A line-by-line coding approach was used to

group meaningful text segments into

descriptive and interpretative codes. These

codes were then organized into broader

themes, such as “Access to Menstrual Hygiene

Products” and “Menstrual Knowledge.” Themes

were refined for coherence, and sub-themes

were identified for additional detail. Two

independent researchers coded the data,

achieving high inter-coder reliability (Cohen’s

Kappa = 0.80) (McHugh, 2012). Participant

validation (a subset of participants, n = 5)

further enhanced credibility through member

checking. The qualitative data were analyzed

under six key identified themes: Menstrual

Knowledge and Awareness, Access to

Menstrual Hygiene Products, Hygiene

Practices, Privacy and Facilities, Stigma and

Myths, and Health and Well-being.

Participants exhibited and shared a range of

understanding about menstruation, from

accurate knowledge to misconceptions. Most

relied on family members, particularly

mothers, for information, but knowledge was

often incomplete.

Information sources included formal

education, community discussions, and family

teachings. However, inconsistencies in the

depth and accuracy of information across

sources affected the participants’

understanding.

“I was not aware of this before going to the

hostel; it was my mother who informed me.

It was an unexpected and quiet transition into

womanhood. Growing up in the Siddi tribal

community, discussions about menstruation

were rare. It was not something we talked

about openly, and information was limited. My

mother’s guidance became crucial but

meanwhile insufficient.”

Participants reported varied experiences

regarding access to menstrual products, with

some using commercial sanitary pads while

others relied on homemade alternatives due

to limited availability in their communities.

Barriers to accessing menstrual hygiene

products included limited availability in local

shops and a lack of awareness about

affordable options, particularly within the

Siddi Tribal community.

“It is very difficult to access menstrual hygiene

products. Availability in our Siddi community

is discouragingly limited. The scarcity in local

shops compounds the challenge, making it

especially difficult for us in this area.”

Participants’ menstrual hygiene practices

varied significantly, with some maintaining

regular cleaning routines, while others

struggled to follow consistent hygiene

practices.

Participants reported different routines

regarding changing sanitary products. While

some changed pads frequently, others relied

on reusable clothes, which were changed

infrequently.

“In my daily routine, I change sanitary pads

or products about 3-4 times a day to maintain

cleanliness and comfort. I make it a point to

clean myself thoroughly twice a day, ensuring

hygiene is a priority. Taking a bath and

following a regular routine contribute to my

overall well-being during menstruation.”

“In my daily routine, I rarely use pads or

products, often relying on clothes that I

replace only once or twice. I usually clean

myself thoroughly in the morning, but hygiene

is not a priority at other times of the day.

Occasionally, I skip baths when I am busy with

household chores.”

Privacy and access to appropriate facilities for managing menstrual hygiene were major

concerns, especially for those living in shared

spaces.

Some participants reported difficulties in

finding private spaces for changing menstrual

products, especially in public or communal

settings, affecting their comfort during

menstruation.

“Maintaining privacy during menstruation is a

significant challenge in our Siddi community.

In shared living spaces, finding a moment of

solitude is difficult. The struggle becomes

more pronounced when it comes to changing

re-usable clothes, pads or managing personal

hygiene.”

Participants shared experiences of cultural

stigma and myths surrounding menstruation,

which often dictated behaviour and reinforced

taboos.

Cultural beliefs influenced the way

menstruation was perceived and managed,

with practices such as isolation during

menarche being common. These practices

affected participants’ sense of normalcy

during their menstrual cycles.

“In our culture, certain concerning practices

emerge when a girl reaches menarche. On

the first day, we are confined to a separate

room, barred from entering the home or

participating in various activities and festivals A new bathroom is also constructed

exclusively for us, meant for our use only.

However, after the fifth day of the menstrual

cycle, this bathroom is closed off, making it

impractical. These deeply rooted practices

have a significant impact on our daily lives.”

Participants reported both physical and

emotional health concerns related to

menstruation, highlighting the link between

menstrual hygiene and overall well-being.

Lack of access to resources and proper

hygiene often led to discomfort, infections,

and emotional distress. Participants

emphasized the need for improved menstrual

education and access to hygiene products to

mitigate these health risks.

“Health issues during menstruation are a

major concern in our Siddi community. The

lack of proper awareness and limited access

to resources exacerbate these challenges.

Women and girls often face discomfort,

infections, and emotional distress.”

Addressing menstrual hygiene behaviours

necessitates a nuanced understanding of

menstrual knowledge and awareness. Our

study uncovered a significant deficiency in

menstrual knowledge within the Siddi Tribal

Community. Our data indicated that while the

majority of women reported normal menstrual

cycles, some experienced irregularities,

specifically longer-than-usual gaps, which

may suggest underlying medical concerns.

None of the participants had a comprehensive

understanding of menstruation prior to its onset, with many perceiving it as the body’s

method of expelling “dirty blood” to prevent

infections. A substantial proportion of the

women were unaware of menstruation before

their first period, with friends being the

primary source of information. Other sources

included mothers and close relatives, while

online programs or advertisements were not

cited, likely due to the limited availability of

electricity in Siddi villages. Dhingra et al.

(2009) found similar results and reported that

menstruation, known locally as “Kapadaanna”

or “Mahavari,” was not fully understood by

young adolescents before its onset. The girls

viewed it as essential for removing “dirty

blood” to prevent infections or diseases.

These challenges reinforce the observations

and calls for enhanced efforts to address the

barriers to menstrual hygiene product

availability.

Our findings show culture and social stigma

are associated with menstruation. These

findings align with Garg and Anand (2015),

showing that cultural beliefs associating

menstruation with impurity lead to various

restrictions for girls and women. Women are

often barred from the “puja” room and face

kitchen restrictions. Menstruating women are

also prevented from offering prayers or

touching holy books due to beliefs about

contamination. Kumar and Srivastava (2011)

noted the unfounded belief that menstruation

emits a smell or ray that spoils preserved

food. Traditional taboos linking menstruation

to evil spirits and practices like burying

menstrual cloths persist in some cultures,

including parts of Asia, despite lacking

scientific basis.

Maintaining privacy during menstruation is a

significant challenge in the Siddi community.

These results align with Mudi et al. (2023),

who found that privacy concerns during

menstruation in tribal communities are deeply

tied to cultural practices. Menstrual cloths are

often concealed under other laundry,

reflecting shame and stigma. The reuse of the

same cloth and poor drying methods increase

infection risks. Traditional beliefs, such as

avoiding baths or handling food during

menstruation, further complicate menstrual

hygiene, exacerbated by limited knowledge

and the perception of menstruation as a divine

curse. Such restrictions and stigma contribute

to increased anxiety, depression, reduced

self-esteem and overall psychological

wellbeing among women.

Our study found minimal use of disposable

absorbents or pads among disadvantaged

groups in the Siddi Tribe, consistent with Ram

et al. (2020). This disparity underscores

systemic challenges that limit access to

essential menstrual hygiene products. Low

usage among marginalized communities is

driven by restricted access, financial

constraints, and cultural norms, compounded

by a lack of menstrual health education. The

preference for reusable old clothes over

sanitary pads among tribal women is driven

by cost, availability, and disposal concerns.

According to Kumari et al. (2021), while child

marriage has a long history in India, it is not

prevalent across all social groups, particularly

among tribal populations. In these tribes,

marrying biologically immature girls is

uncommon, as marriage is intended to fulfill

the couple’s sexual needs. Puberty serves as

a significant milestone, with marriage typically

occurring within 2–6 years after menarche.

Consequently, early menarche may result in

early marriage (Kumari et al., 2021).

However, within the Siddi tribe, marriages

often take place at peak youth age, between

20 to 25 years, with a minimal gap between

menarche and marriage.

Literature indicates low usage of disposable

absorbents,

especially

among

socioeconomically disadvantaged groups,

highlighting an urgent need for targeted

interventions. Strategies should focus on

raising awareness and improving access to affordable disposable pads. Educating women

about the health risks of non-disposable

products is vital, and integrating menstrual

hygiene discussions into routine health worker

visits is necessary to increase usage. The

impact of media in promoting disposable

absorbents is evident, as those with limited

media exposure use them less. Strengthening

outreach and developing targeted programs

for disadvantaged groups, along with

supporting campaigns like “18 to 82” (which

seeks to bridge the gap between the 18% who

use sanitary napkins and the 82% who engage

in unhygienic practices) and Run4Nine (which

strives to ensure no woman or girl is

disadvantaged due to her biology), are

essential. Expanding initiatives such as

Menstrual Hygiene Day induce promoting

menstrual hygiene awareness with support

from celebrities. Social marketing approaches

similar to those in reproductive health could

boost disposable absorbent use. Platforms like

Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram should

integrate menstrual hygiene with adolescent

health initiatives (MoHFW, 2014). Increasing

the availability of affordable products is also

crucial, as shown by Uttar Pradesh’s low

availability and high prices. Directing health

workers to distribute subsidised pads and

expanding school-based programs could

significantly improve access.

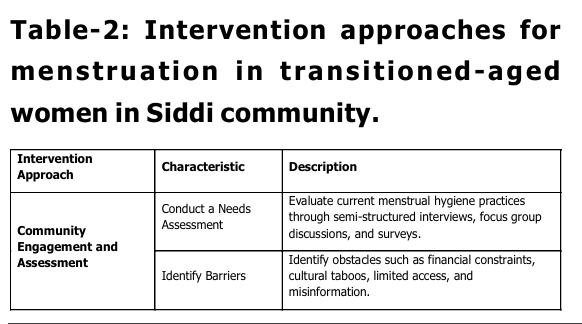

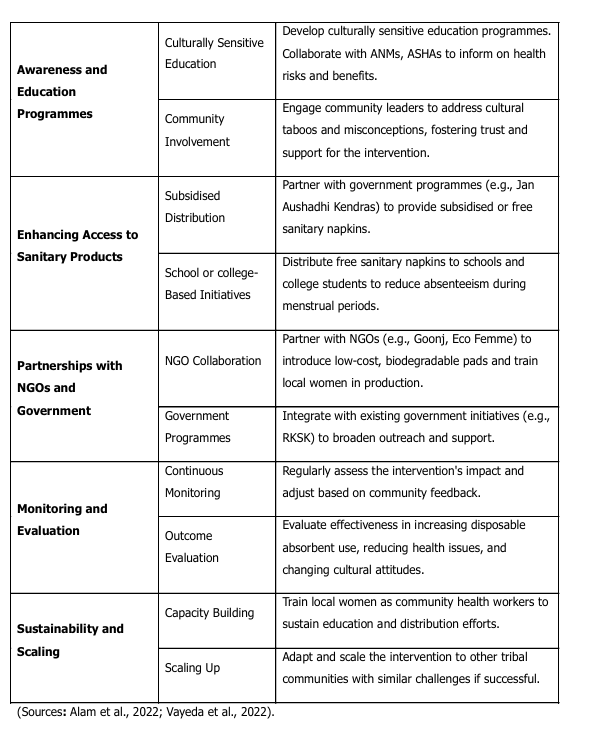

Empowering the Siddi tribe with a

collaborative approach to transform menstrual

hygiene through education, access, and

sustainable intervention (Table-2).

The study underscores the significant need

for targeted strategies to enhance menstrual

hygiene among transition-aged women in the

Siddi Tribal Community. These strategies

should encompass educational outreach,

subsidized sanitary products, and

strengthened support from frontline health

workers. The research reveals significant

gaps in menstrual knowledge, often worsened

by insufficient education and family support,

which contribute to widespread

misconceptions and poor hygiene practices,

leading to both physical and emotional health

issues. Limited access to menstrual products,

particularly in local markets, further

complicates the situation, highlighting the

critical need for reliable and affordable

options. Additionally, cultural norms and

taboos hinder open discussions about

menstruation, while challenges in maintaining

privacy in shared living environments

underscore the necessity for culturally

sensitive solutions. Traditional practices surrounding menarche play a significant role

in daily life, necessitating integrated strategies

supported by well-designed policies and

programs. These interventions should include

comprehensive, culturally relevant educational

initiatives that not only empower women but

also honour traditional values. The study also

highlights the psychological impact of reusing

menstrual products to conceal bloodstains,

linking the low use of disposable absorbents

to socio-economic challenges and a sense of

disempowerment. Addressing these issues

through targeted interventions is crucial for

improving menstrual hygiene, reducing school

or college absenteeism, and fostering both

economic and social empowerment within the

community.

Acknowledgment

We are deeply appreciative of the participants

for sharing their knowledge and experiences

about menstruation. We extend our sincere

thanks to the Siddi community for their

invaluable support and insights into Siddi

cultural practices and environmental factors.

Alam, M. U., Sultana, F., Hunter, E. C., Winch,

P. J., Unicomb, L., Sarker, S., … &

Luby, S. P. (2022). Evaluation of a

menstrual hygiene intervention in

urban and rural schools in Bangladesh:

a

pilot

study. BMC Public

Health, 22(1), 1100.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic

analysis. The journal of positive

psychology, 12(3), 297-298.

Dar, D. R., & Sobhana, H. (2024). Echoes of

Transition: Youth Mental Health in

Crossroads. IAPS Journal of Practice

in Mental Health, 2(1), 20-22.

Dhingra, R., Kumar, A., & Kour, M. (2009).

Knowledge and practices related to

menstruation among tribal (Gujjar)

adolescent girls. Studies on Ethno

Medicine, 3(1), 43-48.

Garg, S., & Anand, T. (2015). Menstruation

related myths in India: strategies for

combating it. Journal of family

medicine and primary care, 4(2), 184

186.

Kumar, A., & Srivastava, K. (2011). Cultural

and social practices regarding

menstruation among adolescent

girls. Social work in public

health, 26(6), 594-604.

Kumari, S., Sood, S., Davis, S., & Chaudhury,

S. (2021). Knowledge and practices

related to menstruation among tribal

adolescent girls. Industrial Psychiatry

Journal, 30(Suppl 1), S160-S165.

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability:

t he kappa statistic. Biochemia

medica, 22(3), 276-282.

Mishra, P. (2020). Periods, perceptions and

practice-a study of menstrual

awareness among adolescent girls in

a tribal district of Odisha, India. Indian

Journal of Public Health Research &

Development, 11(6), 577-585.

MoHFW. (2014). strategy handbook. https://

nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/

rksk-strategy-handbook.pdf

Mudi, P. K., Pradhan, M. R., & Meher, T. (2023).

Menstrual health and hygiene among

Juang women: a particularly

vulnerable tribal group in Odisha,

India. Reproductive Health, 20(1), 55.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., &

Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic

analysis: Striving to meet the

trustworthiness criteria. International

journal of qualitative methods, 16(1),

1609406917733847.

Ram, U., Pradhan, M. R., Patel, S., & Ram, F.

(2020). Factors associated with

disposable menstrual absorbent use

among young women in

India. International Perspectives on

Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46, 223-234.

Sivakami, M., van Eijk, A. M., Thakur, H.,

Kakade, N., Patil, C., Shinde, S., … &

Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2019). Effect

of menstruation on girls and their

schooling, and facilitators of

menstrual hygiene management in

schools: surveys in government

schools in three states in India,

2015. Journal of global health, 9(1).

Torondel, B., Sinha, S., Mohanty, J. R., Swain,

T., Sahoo, P., Panda, B., … & Das, P.

(2018). Association between

unhygienic menstrual management

practices and prevalence of lower

reproductive tract infections: a

hospital-based cross-sectional study

i n Odisha, India. BMC infectious

diseases, 18, 1-12.

Upashe, S. P., Tekelab, T., & Mekonnen, J.

(2015). Assessment of knowledge and

practice of menstrual hygiene among

high school girls in Western

Ethiopia. BMC women’s health, 15, 1

8.

Vayeda, M., Ghanghar, V., Desai, S., Shah, P.,

Modi, D., Dave, K., … & Shah, S.

(2022). Improving menstrual hygiene

management among adolescent girls

i n tribal areas of Gujarat: an

evaluation of an implementation model

integrating the government service

delivery system. Sexual and

Reproductive Health Matters, 29(2),

1992199.

WHO. (2023, October 3). Sanitation. WHO;

World Health Organization: WHO.

https://www.who.int/news-room/

fact-sheets/detail/sanitation