Background: This article discusses the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on fieldwork in social

work education in India. Through an online survey of social work students, the authors explore

key aspects such as modes of fieldwork, satisfaction levels, application of social work methods,

individual and group conferences, and challenges encountered. The study outlines how students

completed their fieldwork using online, offline, or blended formats, depending on the restrictions

imposed by the pandemic and their satisfaction with these modified fieldwork formats. Method:

The article attempts to assess how effectively students were able to apply social work theories

and methods in these adapted fieldwork environments and the adaptation of individual and group

conferences during the pandemic. Result: In addition to this, the article identifies specific

challenges faced by students, such as reduced face-to-face experience, limited community access,

and issues arising from the digital divide. It emphasizes the importance of innovative approaches

to fieldwork in social work education and offers valuable insights for educators, practitioners,

and researchers. Conclusion: The article recommends for a systematic and flexible approach to

fieldwork design, ensuring that students receive comprehensive, hands-on training even during

global crises.

In December 2019, highly contagious virus

identified as COVID-19, emerged and rapidly

spread to multiple countries, catching the

world unprepared. The World Health

Organization (WHO) declared it a pandemic,

urging nations to take immediate action. To

curb the spread of the virus, governments

implemented restrictions on movement,

including widespread lockdowns. The

pandemic and subsequent lockdowns

significantly impacted social work education

both in India and globally (Mishra et al., 2022;

Saumya & Singh, 2022). It reshaped both the

teaching and practice of social work, as

schools and colleges closed, suspended inperson classes, disrupting students’ education e field.

Fieldwork is a crucial aspect of social work

education, enabling students to acquire the

necessary skills and understanding to fulfill

their roles effectively. However, the COVID19 pandemic posed significant challenges,

leading to the suspension of fieldwork for

many students until the next academic term.

There was rapid digitalization of social work

during the pandemic and the growing need

for digital competencies in social work

education was felt. The shift to remote and

virtual modes of learning presented both

opportunities and obstacles for social work

students engaged in fieldwork. Heinsch et al.

(2023) highlighted an 8-week simulation

learning experience, “Social Work Virtual,”

developed to equip students with essential

digital skills, combining both online and faceto-face pedagogical approaches under expert

mentorship. While digital technologies

enabled continued engagement with clients

and agencies, the lack of in-person

interactions presented significant challenges

in developing essential hands-on skills and

establishing meaningful relationships with

communities.

Non-Government organizations (NGOs), which

play a critical role in helping those in need,

were also forced to close temporarily.

Kourgiantakis and Lee (2020) noted that this

disruption particularly affected those working

with vulnerable populations, as social workers,

educators, and students struggled to adapt

to new realities during lockdowns. The

disruption had significant mental distress

among students, including anxiety and ethical

dilemmas, emphasizing the need for improved

support systems during crises (Withrow et al,

2023). Many students reported feelings of

isolation and uncertainty about their future

careers as they were unable to engage

directly with clients (Kourgiantakis & Lee,

2020).

In this background, this article explores how

students updated their fieldwork to changing

circumstances and evaluates new teaching

methods. It aims to explore ways to continue

training students despite the pandemic. It also

deliberates on the challenges faced by social

work students and innovative ways to teach

and learn, in India.

Review of Literature

The fieldwork consists of orientation,

concurrent fieldwork, block placement, rural

camp, study tour and internship. It is the most

important part of social work education

(Botcha, 2012), offering students a chance to

learn from experienced instructors who guide

their practical training.

During the pandemic, educational institutions

in India and worldwide struggled to adapt to

the rapidly changing situation. They faced

unique challenges in ensuring continuity and

quality of fieldwork experiences for their

students. Fieldwork supervisors and students

had to quickly adapt to alternative approaches

for direct in-person fieldwork and supervision.

The sudden transition to virtual platforms

posed significant challenges, as it demanded

that supervisors modify learning plans, adapt

to remote learning activities, implement new

evaluation criteria, and shift to online

supervision. At the same time, students were

required to meet the expected standards of

fieldwork practice in this new format (Saumya

& Singh, 2022). Social work students adopted

innovative ways to complete fieldwork during

the pandemic when offline fieldwork was

impossible (Davis & Mirick, 2021; Morley &

Clarke, 2020). Virtual platforms were used to

facilitate remote client interactions, virtual

site tours, and online seminars with

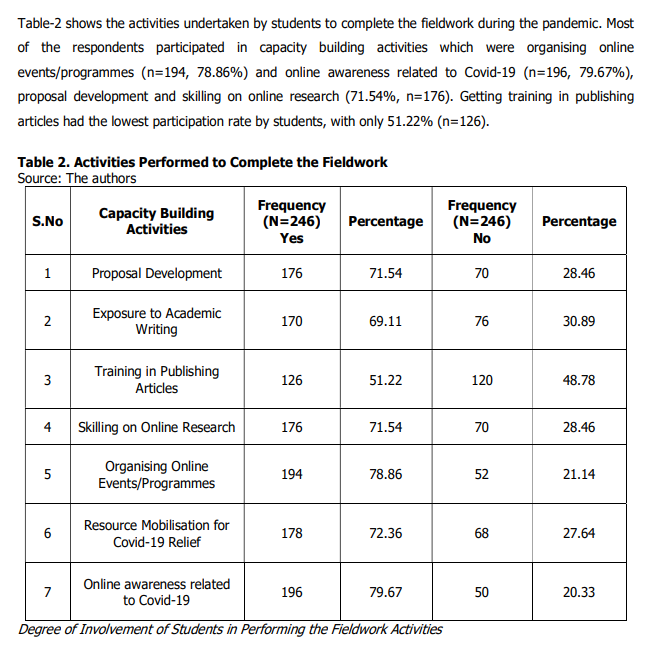

practitioners. The various activities included

learning to develop proposals, improving

academic writing skills, training on publishing

research articles, conducting online research,

organizing online events and programmes,

raising resources for COVID-19 relief, and

creating online awareness about COVID-19

(Morley & Clarke, 2020; Davis & Mirick, 2021;

Pawar & Anscombe, 2015). It was witnessed

both in India and globally that social work

educators demonstrated resilience and

creativity in designing innovative fieldwork

experiences for their students across various

universities.

A study by Withrow, Holland & Simon (2023)

examines the impact of the COVID-19

pandemic on social work students’ field

placements during spring 2020. Through a

national survey, this study reveals varied

support levels from universities and agencies,

highlighting ethical dilemmas faced by

students. The findings inform policy

recommendations for improved crisis

response in social work education. It confirms

the disruptions in field placements, community

outreach, and direct client interactions

necessitating an immediate adaptation to

remote learning models and virtual

interactions (Withrow et al., 2023). Davis &

Mirick (2021) points out that many

organizations have had to stop in-person

services and close their offices, making it

difficult for students to gain experience.

Utilizing both qualitative and quantitative

methods, Apostol et al. (2023) highlight

student perspectives on the shift, emphasizing

challenges with practical activities and student

well-being. They recommend improving

feedback mechanisms, enriching curricula

with resilience programmes, and organizing

peer mentoring post-pandemic to better

prepare students for professional challenges

(Apostol et al., 2023).

The pandemic affected the mental health of

social work students with increased levels of

anxiety, depression, and stress, primarily due

to social isolation, uncertainty about the

future, and the disruption of practical learning

experiences (Hong, 2023). In India, the issue

of digital divide posed challenges with some

students not having access to smartphones

or computers due to financial constraints

(Pandey, 2020). Teachers were not trained or

certified to teach online, making them hesitant

to use technology. Slow internet connections

also made it hard for students and teachers

to attend online classes (Sharma & Singh,

2021). Teachers who were not digitally

qualified could not meet students’ learning

needs and expectations (Bhowmik, 2020).

The Council on Social Work Education (CSWE)

surveyed 197 deans and directors of social

work programmes and 235 field directors in

2020, right after the national emergency was

declared (CSWE, 2020). The survey found that

almost all student placements (97%) were

affected by the pandemic. Some students

(23.8%) had their placements cancelled,

while most students had to adjust their

placements and do alternative activities like

virtual meetings and projects from home

(CSWE, 2020). Another CSWE study found that

most social work students (61.1%) felt their

learning experience got worse after switching

to online learning, and 64.8% of students felt

they learned less. Most students (at least 4

out of 5) preferred in-person classes over

online classes, even after attending online

classes (CSWE, 2020).

In view of few studies on COVID-19 pandemic

and social work training in India, this study

aims to deliberate on the innovative strategies

to manage fieldwork effectively during future

pandemics like COVID-19.

Methods

This study seeks to understand how social

work schools adapted fieldwork during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, it aims to

explore the challenges and innovative

solutions that emerged for doing fieldwork

during the pandemic. The data was collected

from social work students in different schools

of social work across India. Only students who

completed their fieldwork during the COVID 19 pandemic in India were included. To collect

the data, an online questionnaire was

developed and shared through email lists and

social media platforms to reach social work

students in India. Secondary data was

collected through books, articles, and other

published sources. Participating in the study

did not pose any harm or risks, and the

authors obtained consent from the

participants. The authors made sure

participants understood their rights in the

study. The study was approved by the Rajiv

Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development

Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC/2022/08).

A total of 246 social work students from all

over India responded to the study. The data

was analysed using Microsoft Excel. However,

the authors faced a limitation in terms of the

sample size as a relatively small (n=246)

number of students responded out of the total

questionnaires sent.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and

subsequent lockdowns in India, social work

schools had to resort to online methods for

conducting fieldwork. Since students could not

practice social work methods, alternative

training methods were introduced. This led

to the emergence of online fieldwork and

various activities were included to complete

the fieldwork.

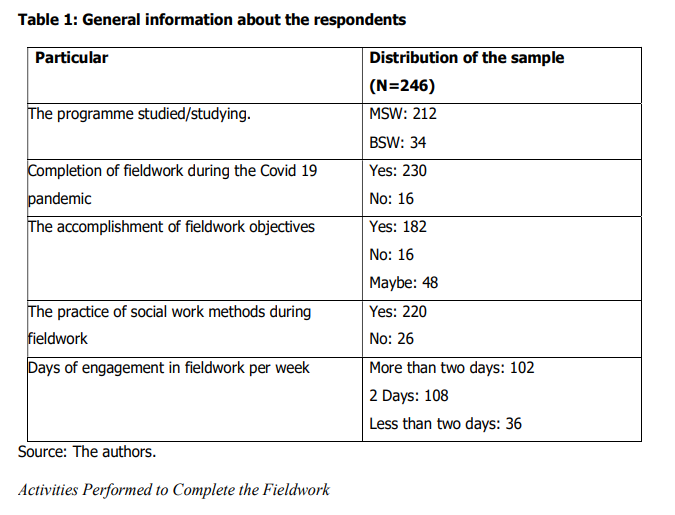

General Information about the Respondents

Table 1 presents data on the distribution of a

sample of 246 students concerning various

aspects of their fieldwork engagement during

the Covid-19 pandemic. The table shows the

different programmes undertaken by students,

with 212 students of MSW and 34 students of

BSW. Most of the students (n=230) completed

their fieldwork during the pandemic, while

only 16 did not. Of those who completed

fieldwork during the pandemic, 182 students

accomplished their fieldwork objectives, while

16 felt they did not. Additionally, 48 students were unsure if they had accomplished their

fieldwork objectives. Most (n=220) students

reported practising social work methods

during their fieldwork, while 26 did not.

Finally, most of the sample, 108 students,

reported engaging in fieldwork for two days

per week, 102 students reported engaging in

fieldwork for more than two days per week,

and 36 students reported engaging in

fieldwork for less than two days per week.

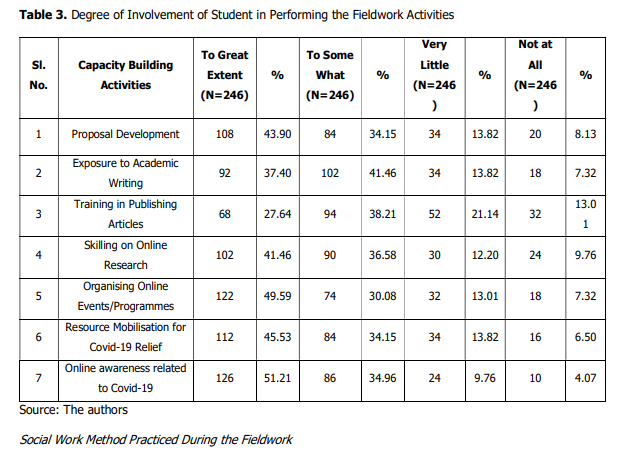

Table 3 represents the students’ level of

involvement in performing the activities as

part of their fieldwork during Covid-19.

According to the table, the capacity-building

activities carried out by the participants were

largely organising online events/programmes (49.59%) and online awareness related to

Covid-19 (51.21%). In contrast, training in

publishing articles (27.64%) and exposure to

academic writing (37.40%) were the least

carried out activities. Additionally, many

participants carried out skilling on online

research (41.46%) and resource mobilisation

for Covid-19 relief (45.53%). The table

suggests that social work students performed

activities directly related to the Covid-19

pandemic, such as online awareness and

resource mobilisation. This is in line with the

social work profession’s emphasis on

addressing social problems during times of

crisis (International Federation of Social

Workers, 2020).

The study shows that social casework was the

most commonly practised method, with

87.80% of the respondents reporting that they

applied it during fieldwork. Social group work

was also widely used, with 85.37% of the

respondents indicating that they practised

this method. Community organisation was the

third most used social work method, with

78.86% of the respondents indicating that they

applied it. Social work research was practised

by 65.85% of the respondents, while social

action was used by 58.54%. Finally, social

welfare administration was the least

commonly practised method, with only 48.78%

of the respondents indicating that they applied

it during their fieldwork. Some respondents did not apply any of the social work methods

included in the survey.

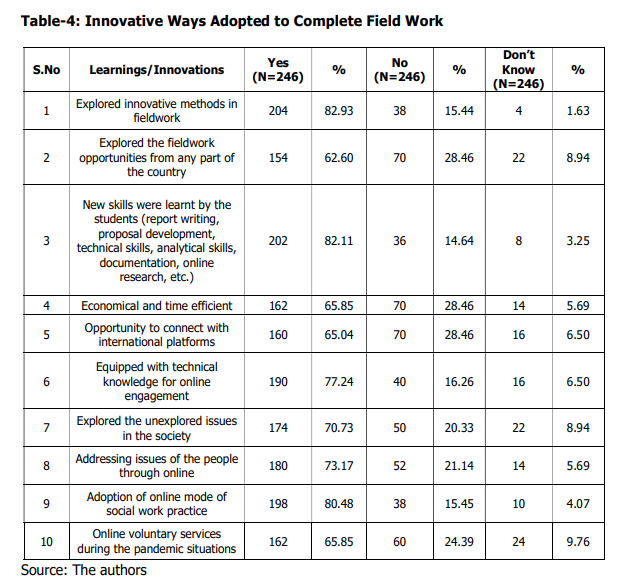

proposal

development, technical skills, analytical skills,

documentation, online research, etc. Other

innovations include being economical and

time-efficient, the opportunity to connect with

international platforms, and being equipped

with technical knowledge for online

engagement, exploring new societal issues,

and addressing people’s issues online. Other

innovations were adopting online modes of

social work practice, adopted by 80.48% of

the respondents, and providing online

voluntary services during pandemic situations.

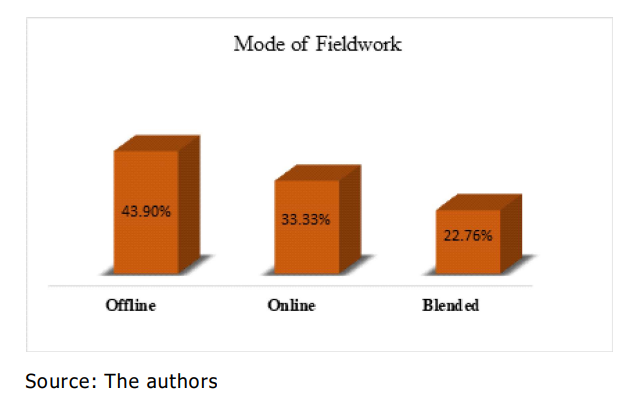

The study’s findings reveal that many of the

students (n=108, 43.90%) completed their

fieldwork offline. Approximately one-third of

the students (n=82, 33.33%) reported using

an online mode to complete their fieldwork.

The remaining students (n=56, 22.76%)

completed their fieldwork using a blended

mode, considered the most suitable method

during the pandemic.

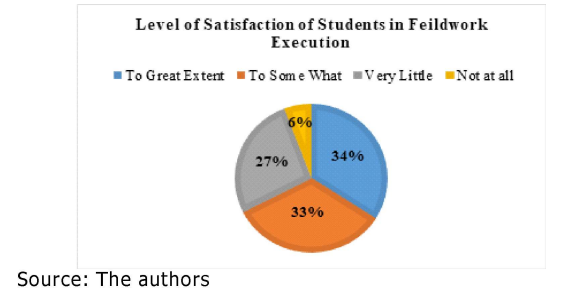

Social work students were asked about their

satisfaction with completing required

fieldwork tasks in accordance with their

school/department’s fieldwork manual. As

depicted in Figure 2, many students (n = 84)

expressed a high level of satisfaction, while

approximately 33% reported being somewhat

satisfied. A small percentage (6%) of

respondents expressed no satisfaction with

their fieldwork experiences during the COVID19 pandemic.

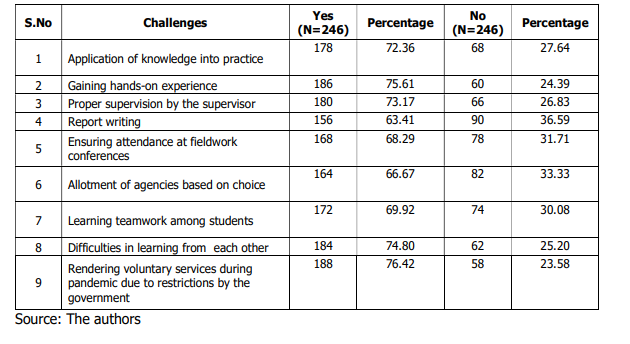

Table-5 represents the challenges faced by

social work students during online fieldwork.

The first challenge was applying classroom

knowledge into practice, which was

experienced by 72.36% of the respondents.

The second challenge was gaining hands-on

experience, reported by 75.61% of the

respondents. Another challenge was not

receiving proper supervision by the supervisor,

which was experienced by 73.17% of the

respondents. Report writing was a challenge

faced by 63.41% of the respondents. Ensuring

attendance at fieldwork conferences was also

one challenge experienced by 68.29% of the

respondents. The allotment of agencies based

on the student’s choice was reported by

66.67% of the respondents. Because of the

online learning mode, teamwork among

students was also a challenge experienced by

69.92% of the students. 76.42% of the

participants reported being unable to provide

voluntary services during the pandemic due

to government restrictions.

When the respondents were asked about their

perception of whether online fieldwork could

be a viable alternative to traditional offline

fieldwork in social work, the findings indicate

that a significant portion of the respondents

(n=108, 44%) did not consider online fieldwork as a substitute for offline fieldwork.

The rationale behind this opinion was that

social work practicum required direct

interaction and engagement with individuals,

groups, communities, and organisations.

These aspects of social work fieldwork cannot

be replicated entirely in an online setting,

where there might be limitations to personal

interactions and on-site assessments. While

online fieldwork can offer new opportunities

for learning and innovative approaches to

social work, it cannot wholly replace the

essential elements of traditional fieldwork in

social work.

When the survey among social work students

asked about their overall experience with

fieldwork during the COVID-19 pandemic,

respondents (n=114, 46%) expressed good

experience. This suggests that despite the

challenges posed by the pandemic, many

students successfully completed their

fieldwork requirements and gained valuable

experience in the fieldwork. However, many

respondents (n=44, 18%) did not like their

fieldwork experience. This could be due to

several reasons, such as difficulty adapting

to the online mode of fieldwork or

experiencing limitations in their ability to

directly engage with individuals, groups,

communities and organisations. It is crucial

to consider the perspectives and experiences

of these students to identify areas for

improvement and ensure that all students

have a positive and meaningful fieldwork

experience.

When asked about individual and group

conferences, most social work students

(71.54%, n=176) reported attending fieldwork

conferences weekly, while 17% (n=42)

attended once every two weeks. Regarding group conferences, almost all students

(95.1%, n=234) attended them, with 73.2%

attending once a week and 13.8% attending

once every two weeks. Since face to face

supervision was not feasible, roughly 83% of

students reported that their supervisor used

video conferencing platforms like Zoom,

Google meet, and Webex for supervision,

while 10% were supervised by their agency

supervisor.

The Role of Social Work Profession During

Pandemic Situations like Covid-19

Social work utilises knowledge and principles

from human behaviour and social systems to

address social issues and assist those in need.

The social work profession has a significant

role in raising awareness, providing

psychosocial support, and promoting social

inclusion for populations that are most at risk

(Okafor, 2021). Upon asking, the majority of

social work students (65.9%, n=162) strongly

agreed, and 26% (n=64) agreed that the

social work profession has an important role

to play in addressing emergencies such as the

COVID-19 pandemic by raising awareness,

providing temporary relief, preventing the

spread of the virus, and educating people

about vaccination. However, the Indian

government restricted social workers during

the pandemic, only allowing those engaged

in essential services to leave their homes.

Social workers were not considered frontline

workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in

India, so they could not provide their services

(IFSW, 2020; Onalu et al., 2020).

A total of 246 BSW/MSW students responded

to this study, out of which most of them have

done the fieldwork, accomplished their

fieldwork objectives and practised the

methods of social work during their fieldwork

during COVID-19 pandemic. The study

revealed that innovative ideas and activities

were devised to complete fieldwork during the pandemic. The social work students were

actively involved in various capacity-building

activities such as organising events/

programmes and online awareness related to

COVID-19. Training in publishing articles,

exposure to academic writing, conducting

online research and resource mobilisation for

COVID-19 relief were some other activities

being carried out by students. These findings

align with the social work profession’s

emphasis on addressing social problems

during times of crisis, as highlighted by the

International Federation of Social Workers

(2020). The study reveals that social work

students played a crucial role in responding

to the COVID-19 pandemic by actively

engaging in fieldwork activities that addressed

the community’s needs.

It was found that social casework was the

most widely used method, followed by social

group work and community organisation,

among social work students during online

fieldwork. This indicates that most social work

students have a strong foundation in

traditional social work methods that focus on

working with individuals, groups, and

communities. Social work research and social

action were also commonly used, while social

welfare administration was the least used

method. These findings highlight the need for

a broad-based social work curriculum that

exposes students to diverse methods and

approaches. Additionally, the students adopted

online modes of social work practice,

demonstrating their adaptability and resilience

in the face of adversity. Overall, these findings

highlight the resourcefulness of social work

students in adapting to the challenges posed

by the pandemic and the potential of

technology to enable effective social work

practice.

One-third of the students used online mode

to complete their fieldwork while some of the

students completed their fieldwork using a

blended mode. This highlights the need for social work programmes to provide students

with the necessary digital skills and resources

to conduct fieldwork using innovative

modalities. Most social work students were

satisfied with fieldwork completion.

It was reported that students faced challenges

applying classroom knowledge into practice

and gaining hands-on experience. Some

reported not receiving proper supervision,

facing difficulties with report writing, and

ensuring attendance at fieldwork conferences.

The allocation of agencies based on student

choice and teamwork was also identified as

challenge. These findings provide important

insights into the challenges social work

students faced during online fieldwork and can

help develop strategies to address these

challenges in the future (Kourgiantakis & Lee,

2020).

The study reveals that the social work

students did not consider online fieldwork as

a substitute for offline fieldwork due to the

direct interaction and engagement required

in social work practicum, which cannot be

entirely replicated online. While online

fieldwork can provide new opportunities and

innovative approaches, it cannot replace the

essential elements of traditional face to face

fieldwork in social work. Social work students

understand the importance and value of the

social work profession in responding to crises

like the COVID-19 pandemic. They recognize

that social workers play a crucial role in

raising awareness, providing relief, preventing

the spread of the virus, and educating people

about vaccination (Davis & Mirick, 2021;

Lomas et al., 2022).

The study explores the challenges and

innovations in adapting fieldwork practices

during COVID-19. The pandemic disrupted

traditional methods, leading to a shift to online

and blended approaches. Students faced

difficulties like lack of hands-on experience and digital access issues but adapted by

embracing digital tools and creative

strategies, including online events, awareness

campaigns, research proposals, and training

in publishing. However, despite these

interruptions, the foundational values of social

work—service, social justice, dignity, human

relationships, integrity, and competence—

remained central, but the methods for

practicing and teaching these values had

evolved (Saumya & Singh, 2022). The study

highlights the importance of supporting

students through guidance and technology,

advocating for hybrid models in future crises.

Apostol, A.-C., Irimescu, G., & Radoi, M.

(2023). Social work education during

the COVID-19 pandemic—Challenges

and future developments to enhance

students’ wellbeing. Sustainability,

15(9009), 1–28. https://doi.org/

10.3390/su15119009

Bhatt, S. (2021). Students Enrollment in

Social Work Courses in Indian Higher

Educational Institutions: An

Analysis. Space and Culture,

India, 9(2), 50-64.

Bhowmik, A. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak and

edification: Challenges and trends in

higher education of India. In K. Kaur

& L. K. Sharma (Eds.), The changing

India amidst Covid-19 catastrophe

(pp. 101–108). Asian Press Books.

Botcha, R. (2012). Retrospect and prospect

of professional social work education

in India: A critical review. Perspective

in Social Work, XXVII(2), 14–28.

Council on Social Work Education. (2020).

CSWE statement on field hour

reduction. Retrieved from https://

c sw e . or g / Ne w s/ Ge ne ra l- New sArchives/CSWE-Statement-on-FieldHour-reduction

Council on Social Work Education. (2020c).

Social work student perceptions:

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on

educational experience and goals.

Retrieved from https://cswe.org/

getattachment/ResearchStatistics/

S o c i a l – W o r k – S t u d e n t –

Perceptions.pdf.aspx

Davis, A., & Mirick, R. G. (2021). COVID-19

and social work field education: A

descriptive study of students’

experiences. Journal of Social Work

Education, 57(sup1), 120–136. https:/

/ d x . d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 8 0 /

10437797.2021.1929621

Heinsch, M., Cliff, K., Tickner, C., & Betts, D.

(2023). Social work virtual: Preparing

social work students for a digital

future. Social Work Education. https:/

/ d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 8 0 /

02615479.2023.2254796

Hong, C. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19

pandemic on mental health in social

work students: A scoping review and

call for research and action. Social

Work in Mental Health, 21(3), 329–

346. https://doi.org/10.1080/

15332985.2023.2196361

Lomas, G., Gerstenberg, L., Kennedy, E.,

Fletcher, K., Ivory, N., Whitaker, L., &

Short, M. (2022). Experiences of

social work students undertaking a

remote research-based placement

during a global pandemic. Social Work

Education, 1-18.

Morley, C., & Clarke, J. (2020). From crisis to

opportunity? Innovations in Australian

social work field education during the

COVID-19 global pandemic. Social

Work Education, 39(8), 1048–

1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/

02615479.2020.1836145

Okafor, A. (2021). Role of the social worker

in the outbreak of pandemics (A case

of COVID-19). Cogent

Psychology, 8(1), 1939537 Onalu, C. E., Chukwu, N. E., & Okoye, U. O.

(2020). COVID-19 response and social

work education in Nigeria: Matters

arising. Social Work Education, 39(8),

1037–1047. https://dx.doi.org/

10.1080/02615479.2020.1825663

Pandey, K. (July 30, 2020). COVID-19

lockdown highlights India’s great

digital divide. Down To Earth.

Retrieved December 17, 2021, from

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/

news/governance/covid-19-lockdownhighlights-india-s-great-digital-divide72514

Pawar, M., & Anscombe, B. (2015). Reflective

social work practice: Thinking, doing

and being. Cambridge University Press

Rahman, D. (2020). A reckoning for online

learning in times of crisis. The Star.

Saumya & Singh T. (2022). Fieldwork in the

Times of COVID–19: A Case Study,

Journal of Social Work Education and

Practice, Volume 7; Issue 1

Sharma, D., & Singh, A. (2021). e-Learning

in India during Covid-19: Challenges

and opportunities. European Journal

of Molecular & Clinical Medicine, 7(7),

6199–6206.

Withrow, J., Holland, R. S., & Simon, R. M.

(2023). Understanding the impact of

the COVID-19 pandemic on social

work field placements: A student’s

perspective. Field Scholar, 13(1).

Zuchowski, I., Collingwood, H., Croaker, S.,

Bentley-Davey, J., Grentell, M., &

Rytkönen, F. (2021). Social work ePlacements during COVID-19:

Learnings of staff and students.

Australian Social Work, 74(3), 373–

386. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/

0312407X.2021.1900308