Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

QUALITY OF LIFE AMONG PARENTS OF CHILDREN WITH TYPE 1

DIABETES MELLITUS

Jayachandran M R1 & Laxmi2

1Medical Social Service Officer, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar,

2Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Central University of Kerala,

Correspondence: Jayachandran M R, e-mail: msso_jayachandran@aiimsbhubaneswar.edu.in

ABSTRACT

Background: The quality of life is considered exceptionally imperative for the family of children

with unremitting infection. Parents have a critical part in choosing the quality of life among

families of children with chronic illnesses. Aim: The study aims to assess the level of quality of

life and to measure the socio-demographic profile among parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus. Methods and Materials: The study used an Explanatory research design, and

quantitative data collection was employed in this study. Results: The results of the current

study showed that parents of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus reported higher levels of

quality of life in the physical, social, and environmental domains. When compared to other quality

of life domains, the psychological quality of life domain has demonstrated a lower quality of life.

Conclusion: The findings of this study will assist various stakeholders, including policymakers,

medical professionals, medical social workers, mental health specialists, and researchers, in

comprehending the challenges faced by parents and caregivers.

Keywords: Quality of Life, Chronic illness, Diabetes Mellitus, Parents, Children.

INTRODUCTION

A person’s or a community’s overall state of

well-being is regarded as their quality of life,

and health-related studies typically assess life

quality (Sathyananda & Manjunath, 2017).

According to the World Health Organization,

quality of life means “Individuals’ perception

of their position in life in the context of the

culture and value systems in which they live

and in relation to their goals, expectations,

standards and concerns. It is a broad-ranging

concept affected in a complex way by the

persons’ physical health, psychological state,

level of independence, social relationships,

and their relationship to salient features of

their environment’’ (The WHOQOL Group,

1995, p.1403). The World Health Organization

has defined four domains of measuring quality

of life, which are physical, psychological, social

relationships, and environmental factors.

Physical health refers to human functions such

as daily life, sleep, work capacity, rest,

energy, discomfort, weakness, and

medication. Psychological health includes an

individual’s thinking, feelings, appearance,

mental background, focus, and self

confidence. Social relationship creates

individual support systems, sexual needs, and

relationships with others. Environmental

factors include an individual’s ability to

appreciate freedom, the economy,

transportation, home and other environments,

l eisure activities, health services, skill development, and climate change (World

Health Organization, 1996). Quality of life

evaluates “an individual’s sense of wellbeing

and the degree to which he or she can

participate in the human experience” (Zhan,

1992, p. 779).

The quality of life is considered exceptionally

imperative for the family of children with

unremitting infection (Toledano-Toledano et

al., 2020; Feeley et al., 2014). Parents have

a critical part in choosing the quality of life

among families of children with chronic

illnesses (Janse et al., 2005). Appraisal of

quality of life among parents of children with

chronic illnesses is considered vital, as the

appraisal is based on the parental quality of

life, such as social, psychological, and well

being (Abreu Paiva et al., 2019). The severity

of chronic illness and the family’s financial

status are fundamental components of

parental quality of life (Siboni et al., 2019).

Children with persistent ailments directly

influence family and parental quality of life.

The parental quality of life depends on the

seriousness of the child’s illness and how

much time is spent caring for the affected

children. The parents of children with chronic

illness and their quality of life influence the

family’s social, psychological, and medical

support (Spore, 2012). Chronic diseases are

recognized to affect family circumstances

significantly and create unpleasant

circumstances. Parents’ stress may lead to

confusion, anger, time constraints, isolation,

and bitterness (Cherry, 1989). When the child

features a persistent ailment, diverse

variables such as social, mental, physical, and

monetary stability influence the parent’s

quality of life (Zhang, Wei, Shenand, and

Zhang, 2015). Chronic illness is considered a

challenging circumstance for families; the

child’s sickness impacts everyday activities.

Great quality of life is fundamental for these

families (Amirian et al., 2017). Children with

l ong-term persistent conditions have

adversely influenced their parents quality of

life (Witt et al., 2010). Type 1 diabetes mellitus

is considered a disease and needs lifelong

medical treatment (Vehik et al., 2007).

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is considered

childhood diabetes, but it can occur in people

of any age. Currently, there is no vaccine to

prevent this disease. A person with type 1

diabetes can live a healthy life, but they need

diabetes test equipment, continuous insulin

hormone, diabetes education, and social

support. Type 1 diabetes is caused by an

autoimmune problem and affects the immune

system of the beta cells of the pancreas, which

produce the insulin hormone in the human

body. In this case, the pancreas does not

produce enough or less insulin in the human

body. The acute cause of type 1 diabetes is

unknown. Type 1 diabetes is considered a

chronic disease in childhood (Kahanovitz,

Slussand, and Russell, 2017). Parents play a

vital role in the administration of type 1

diabetes mellitus, and the parents have to give

quality well-being care to their children with

type 1 diabetes mellitus (Uhm & Kim, 2020).

Poor communication, increased family conflict,

decreased adaptation, and poor support lead

to serious issues among parents of children

with type 1 diabetes mellitus (Almeida, 1995).

The adapting techniques of parents of children

with type 1 diabetes mellitus have affected

the parental quality of life (Pierce, Kozikowski,

Lee, and Wysocki, 2017). Parents of children

with type 1 diabetes mellitus were faced with

diverse psychosocial and physical issues

related to caring for children with type 1

diabetes. Numerous responsibilities must be

fulfilled in caring for their child with type 1

diabetes (Spezia, Faulkner, & Clark, 1998).

The well-being status of children with Type 1

diabetes has impacted their parents’ quality

of life (Herbert et al., 2014). In this context,

the study aims to assess the level of quality

of life and to measure the socio-demographic

profile among parents of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

METHODS & MATERIALS

Explanatory research design and quantitative

data collection were employed in this study.

The convenience sampling technique was

employed to get information from

respondents. The study’s participants are

parents of children with diabetes mellitus who

are registered with Kerala’s Mittayi Project.

The Kerala state government oversees the

Mittayi Project, which aims to support children

with type 1 diabetes and their families

(Mittayi, 2017). Parents of children with type

1 diabetes mellitus are the study’s

participants, and organised interview

schedules were used to gather data from the

respondents. 338 samples in all were taken

from the Mittayi project area. The Mittayi

Project granted permission to carry out the

study. The Central University of Kerala’s

institutional human ethics committee accepted

the research.

The respondents’ socio-demographic profile

included details about the age, gender, marital

status, type of family, parents’ education,

parents’ job, and gender of the child with type

1 diabetes. The parents of children with type

1 diabetes mellitus were asked to rate their

quality of life using the World Health

Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL

BREF, 1996). The 26 statements that make up

the scale’s subdomains include environment,

social relationships, psychology, and physical

health. Based on the raw score, the WHO

quality of life BREF score was computed and

then transformed to a range of zero to one

hundred. A higher score denoted a greater

standard of living, whereas a lower score

showed a poorer standard of living (World

Health Organization, 1996).

RESULTS

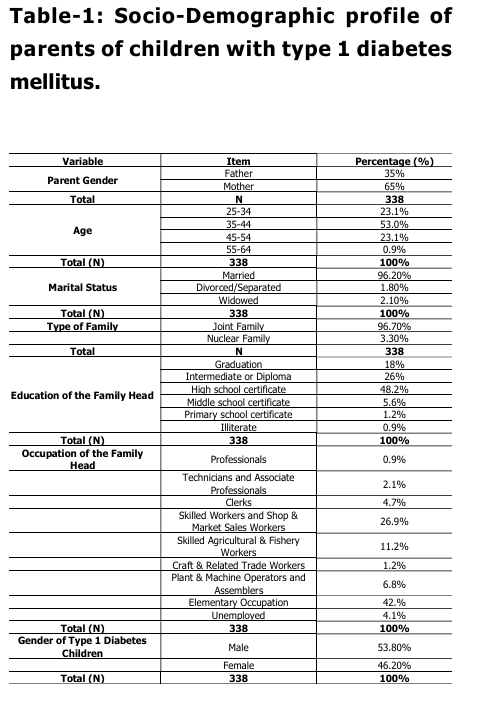

Table-1 above shows that 65 percent of

parents are female and 35 percent of parents

are male. 53 Percentage of the parents of

children with type 1 diabetes mellitus were in

the age group of 35 to 44. 23.1 percent of

parents of type 1 diabetes children belong to

the age group of 25 to 34 years. Another 23.1

percent of parents of children with type 1

diabetes mellitus were in the age group of 45

to 54. A small proportion (0.9 percent)

belongs to the 55 to 64-year age group. The

marital status: 96.20 percent of parents of

children with diabetes mellitus were married

and living with their spouse, followed by 2.10

percent of parents who reported their marital

status as widowed, and 1.80 percent of

parents of children with diabetes mellitus

included in the study were divorced or

separated. Type of family: 96.70 percent of

parents of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus belong to the nuclear family system.

The remaining 3.30 percent of parents of type

1 diabetes children are living in the joint family

system. Parents’ Education: 48.2 percent of

parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus have a high school education, and

only 0.9 percent of the parents were illiterate.

Parents Job: 42 percentage had an

elementary occupation, which was followed

by Skilled Workers and Shop & Market Sales

Workers who formed 26.9 percentage of the

total respondents, Skilled Agricultural &

Fishery Workers are 11.2% percentage, Plant

& Machine Operators and Assemblers form

6.8% percentage of total respondents, Clerks

made 4.7 percentage of the total respondents’

pool. 4.1 percent of respondents were

unemployed, Technicians and Associate

Professionals form 2.1 percent of the total

respondents, Craft & Related Trade Workers

are 1.2 percent, and professionals are 0.9

percent of the total percentage. Diabetes

Child Gender: 53.80 percent of children are

boys, and 46.20 percent of children are girls.

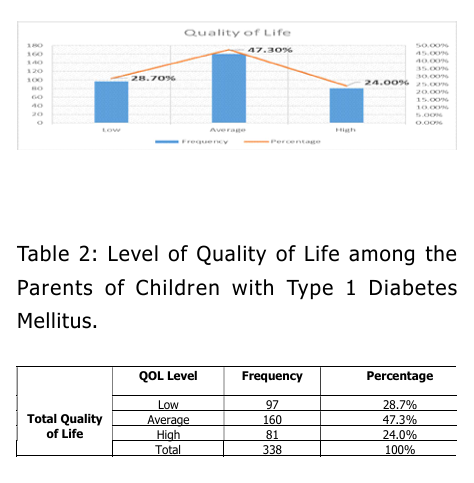

Figure-1: Level of Quality of Life among the

Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes

Mellitus.

Figure-1: Level of Quality of Life among the

Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes

Mellitus.

The result showed the quality of life among

parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus. 47.3 percent of parents of children

with type 1 diabetes mellitus reported an

average level of quality of life. 28.7 percent

of parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus showed a low level of quality of life.

24 percent of parents of children with type 1

diabetes mellitus reported a high level of

quality of life.

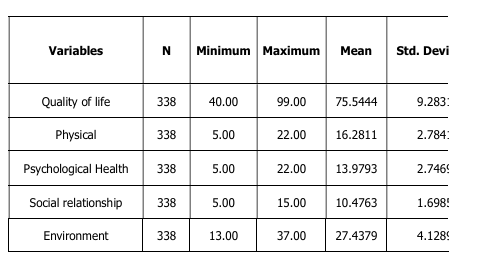

Table 3: Descriptive statistics of quality of life

among the Parents of Children with Type 1

Diabetes Mellitus

The study showed that the minimum and

maximum points of the total quality of life

were 40 and 99. The mean score of parents

of children with type 1 diabetes was 75.54,

and the standard deviation was 9.28. The

physical quality of life score showed a

minimum and maximum quality of life

composite score of 5 and 22. The mean score

of parents of children with type 1 diabetes

was 16.28, and the standard deviation was

2.78. The minimum score in the field of

psychological quality of life was 5, and the

maximum score was 22 for parents. The

mean score was 13.97, and the Std Deviation

score was 2.74. Parents of children with type

1 diabetes reported a minimum social quality

of life score of 5 and a maximum score of 15.

The mean score was 10.47, and the parental

standard deviation was 1.69. The minimum

environmental quality score of parents of

children with type 1 diabetes was 13, and the maximum score was 37. The mean score of

27.43 and standard deviation score of 4.12

showed the quality of life of the parents in

the environment.

The results of the current study showed that

parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus reported higher levels of quality of

life in the physical, social, and environmental

domains. When compared to other quality of

life domains, the psychological quality of life

domain has demonstrated a lower quality of

life.

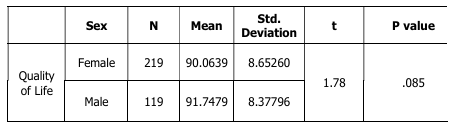

Table 4: t-test for Quality of Life among the

Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes

Mellitus based on Parents’ Gender

The Quality of Life among Parents of Children

with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: The t value

achieved is 1.78 (p>0.05), as the above table

demonstrates. At the 0.05 level of

significance, the t values are greater than the

table value of 1.96. This indicates that there

is no significant difference between the

parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus who are male or female. Therefore,

i t may be said that the quality of life

experienced by male and female parents is

equal.

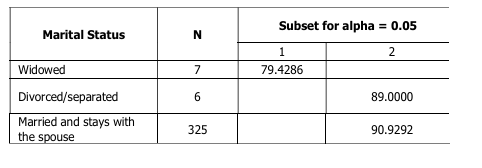

Table 5: ANOVA test for Quality of Life among

the Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes

Mellitus based on Marital Status

The above table describes the F value

obtained for quality of life among parents of

children with type 1 diabetes mellitus as 6.47

(p<0.05), and these F values are greater than

the table value 4.60 at the 0.05 level of

significance. That means there is a significant

difference in the Quality of Life among parents

of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus based

on the marital status of the parents. To find

out the difference among the marital statuses,

Scheffer’s post hoc test was applied for

analysis.

Table 5.1: Scheffe post hoc test Quality of Life

among the Parents of Children with Type 1

Diabetes Mellitus based on Marital Status

Table 7.1 indicates the Scheffe post hoc test

of quality of life based on the marital status

among parents of children with type 1

diabetes mellitus. The parents who are

married and stay with their spouse category

have reported a high mean score (57.60)

compared to other marital categories. So, it

can be concluded that there is an increased

level of Quality of Life among the parents who

live together.

DISCUSSION

The current study set out to evaluate the

quality of life for parents whose children had

been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. type 1

diabetes mellitus is a chronic, lifelong illness.

The family is the one who has to take care of

their sick child the most. According to the

current study, parents of children with type 1

diabetes mellitus showed a marked decline

in their quality of life. According to Witt et al. (2010), parents of children with chronic

illnesses reported worsening mental health

problems and a lower quality of life for their

children. Diabetes mellitus type 1 is regarded

as a chronic condition that has an adverse

impact on the administration of health care

(Ozyazýcýoglu, Avdal and Saglam, 2017). The

primary determinants of the diabetes-related

quality of life for parents of children with type

1 diabetes mellitus have been found to be

family support and glucose management

(Hirose, Beverly and Weinger, 2012). Concerns

regarding their children’s diabetes problems

are a persistent concern for parents of

children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes

mellitus (Hilliard, Herzer, Dolan and Hood,

2011). A similar result was found in a study

by Toledano-Toledano et al., (2020) based on

the WHO Quality of Life BREF tool, which found

that 59.1 percent reported average or

average overall quality of life. and then 33.2

percent reported high overall quality of life

and 6.7 percent reported low quality of life

among parents of children with chronic

conditions. Wiedebusch, Pollmann, Siegmund,

and Muthny (2008) found moderate parental

quality of life for parents of children with

hemophilia. Spezia Faulkner and Clark

reached a similar conclusion (1998); Keklik,

Bayat and Baºdaº (2020), where the author

observes at the average quality of life of

parents of children with type 1 diabetes.

Hilliard, Herzer, Dolan, and Hood, (2011)

documented that parental care for children

with diabetes complications affected the

quality of life of parents of children with type

1 diabetes.

The results of the current study showed that

parents of children with type 1 diabetes

mellitus reported higher levels of quality of

life in the physical, social, and environmental

domains. When compared to other quality of

life domains, the psychological quality of life

domain has demonstrated a lower quality of

life. Keklik, Bayat, and Baºdaº (2020) reached

a similar conclusion about the average

psychological quality of life of parents of

children with type 1 diabetes. Mahani,

Rostami, and Nejad (2013) note that the

psychological domain of parents’ quality of life

was related to their children’s illnesses.

Delamater et al. (2001) documented that

psychosocial factors play an important role in

t he management of diabetes and in

determining the quality of life of parents.

Thorsteinsson, Loi, and Rayner (2017)

described that increasing the psychological

quality of life of parents of children with type

1 diabetes requires adequate parental social

support. The same conclusion was reached

by Yamada et al., (2012), where the author

observes that the deterioration of the quality

of life of parents related to mental health

occurred in parents of children with

developmental disorders. Koc, Bek, Vurucu,

Gokcil and Odabasi (2019) found that the

psychological health of parents of children with

epilepsy impaired quality of life and was

associated with a decrease in parental

emotional well-being. The present study’s

parents who are married and stay with their

spouse category have reported a high mean

score (57.60) compared to other marital

categories. So, it can be concluded that there

is an increased level of Quality of Life among

the parents who live together. The results of

the study conducted by Toledano-Toledano et

al. (2020) show that there is a significant

difference in the marital status and quality of

l ife of parents of children with chronic

diseases. The results of the study by Uhm and

Kim (2020) suggest a similar result, where

the authors found a significant difference in

the marital status and quality of life of parents

of children with type 1 diabetes. The same

conclusion was reached by Faulkner and Clark

(1998), who found that parents of children

living together reported a better quality of life

compared to widowed, separated, and

divorced parents. A growing body of evidence suggests that

caring for these children puts a strain on

parents. Coping with the negative

consequences of care delivery, developing and

i mplementing realistic and appropriate

response strategies is a major challenge. The

stakeholders of chronic illness should also

focus on the mental health of parents of

children with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

According to the aforementioned study

results, parents frequently perceive that

managing their child’s type 1 diabetes mellitus

has an adverse effect on their lives. The

parents are unquestionably the centre of the

family; they must not only manage the

medical concerns of their ill child but also keep

the house in order. Hence, it is the duty of

mental health specialists to take on this task

and offer care to this group that is both in

need and vulnerable. In order to give parents

of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus

greater and more targeted support and

interventions, policymakers must take these

findings into consideration.

CONCLUSION

The study found that quality of life domains

such as physical, social relationships and

environment reported improvements in quality

of life for parents of children with type 1

diabetes. The psychological domain of quality

of life showed a decrease in quality of life

compared to other domains of quality of life.

To summarize, the findings of this study will

assist various stakeholders, including

policymakers, medical professionals, medical

social workers, mental health specialists, and

researchers, in comprehending the challenges

faced by parents and caregivers. This will

facilitate the development of programmes and

i nitiatives aimed at promoting the

psychosocial well-being of parents of children

with chronic illnesses.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE SCOPE

This study has potential limitations. A

limitation was the use of a cross-sectional

design. The study did not take into account

the history/profile of children with type 1

diabetes, which would have helped to compare

the mental state of the parents and the health

status of the child with type 1 diabetes. In

the future, a study of parents of children with

type 1 diabetes mellitus should be conducted

on the condition of the children with a

longitudinal study design, because type 1

diabetes mellitus is identified as a lifelong

chronic illness and needs to be assessed

through the psychosocial variables from time

to time.

REFERENCES

AbreuPaiva, L. M., Gandolfi, L., Pratesi, R.,

Harumi Uenishi, R., Puppin Zandonadi,

R., Nakano, E. Y., & Pratesi, C. B.

(2019). Measuring Quality of Life in

Parents or Caregivers of Children and

Adolescents with Celiac Disease:

Development and Content Validation of

the Questionnaire. Nutrients, 11(10).

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102302

Almeida, C. M. (1995). Grief among parents

of children with diabetes. The

Diabetes educator, 21(6), 530–532.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 1 77 /

014572179502100606

Amirian, H., Solimani, S., Maleki, F., Ghasemi,

S, R., R., S., & Gilan N, R. (2017). A

Study on Health-Related Quality of

Life, Depression, and Associated

Factors Among Parents of Children

with Autism in Kermanshah, Iran.

Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and

Behavioral Sciences, 11(2). https://

doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.7832.

Cherry D. B. (1989). Stress and coping in

families with ill or disabled children:

application of a model to pediatric

therapy. Physical & occupational

therapy in pediatrics, 9(2), 11–32. Delamater, A. M., Jacobson, A. M., Anderson,

B., Cox, D., Fisher, L., Lustman, P.,

Rubin, R., Wysocki, T., & Psychosocial

Therapies Working Group (2001).

Psychosocial therapies in diabetes:

report of the Psychosocial Therapies

Working Group. Diabetes care, 24(7),

1286–1292. https://doi.org/10.2337/

diacare.24.7.1286

Faulkner, M. S., & Clark, F. S. (1998). Quality

of life for parents of children and

adolescents with type 1 diabetes. The

Diabetes educator, 24(6), 721–727.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 1 77 /

014572179802400607

Feeley, C. A., Turner-Henson, A., Christian,

B. J., Avis, K. T., Heaton, K., Lozano,

D., & Su, X. (2014). Sleep Quality,

Stress, Caregiver Burden, and Quality

Of Life in Maternal Caregivers of

Young

Children

with

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Journal

of Pediatric Nursing, 29(1), 29–38.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 16 /

j.pedn.2013.08.001

Herbert, L. J., Clary, L., Owen, V., Monaghan,

M., Alvarez, V., & Streisand, R. (2014).

Relations among school/daycare

functioning, fear of hypoglycaemia

and quality of life in parents of young

children with type 1 diabetes. Journal

of Clinical Nursing, 24(10), 1199

1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/

jocn.12658

Hilliard, M. E., Herzer, M., Dolan, L. M., &

Hood, K. K. (2011). Psychological

screening in adolescents with type 1

diabetes predicts outcomes one year

later. Diabetes Research and Clinical

Practice, 94(1), 39–44. https://

d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 /

j.diabres.2011.05.027

Hirose, M., Beverly, E. A., & Weinger, K.

(2012). Quality of Life and

Technology: Impact on Children and

Families With Diabetes. Current

Diabetes Reports, 12(6), 711–720.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-012

0313-4

Hsieh, R. L., Huang, H. Y., Lin, M. I., Wu, C.

W., & Lee, W. C. (2009). Quality of

life, health satisfaction and family

impact on caregivers of children with

developmental delays. Child: care,

health and development, 35(2), 243

249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365

2214.2008.00927.x

Janse, A. J., Sinnema, G., Uiterwaal, C. S. P.

M., Kimpen, J. L. L., & Gemke, K. J. B.

J. (2005). Quality of life in chronic

illness: Perceptions of parents and

paediatricians. Archives of Disease in

Childhood, 90(5), 486–491. https://

doi.org/10.1136/adc.2004.051722

Kahanovitz, L., Sluss, P. M., & Russell, S. J.

(2017). Type 1 Diabetes – A Clinical

Perspective. Point of care, 16(1), 37

40. https://doi.org/10.10 97/

POC.0000000000000125

Keklik, D., Bayat, M., & Baºdaº, O. (2020).

Care burden and quality of life in

mothers of children with type 1

diabetes mellitus. International Journal

of Diabetes in Developing Countries.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-020

00799-3

Keklik, D., Bayat, M., & Baºdaº, O. (2020).

Care burden and quality of life in

mothers of children with type 1

diabetes mellitus. International Journal

of Diabetes in Developing Countries.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-020

00799-3

Koc, G., Bek, S., Vurucu, S., Gokcil, Z., &

Odabasi, Z. (2019). Maternal and

paternal quality of life in children with

epilepsy: Who is affected more?

Epilepsy & Behavior, 92(1), 184–190.

h t t p s : / / d o i . o r / 1 0 . 1 0 1 6 /

j.yebeh.2018.12.029 Mahani, M. K., Rostami, H. R., & Nejad, S. J.

(2013). Investigation of Quality-of-Life

Determinants Among Mothers of

Children with Pervasive Developmental

Disorders in Iran. Hong Kong Journal

of Occupational Therapy, 23(1), 14

19.

https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.hkjot.2013.03.002

Mittayi.(2017).Mittayi programme under

Kerala social security mission.

Retrieved

from

https://

www.mittayi.org/home/services

Ozyazýcýoglu, N., Avdal, E. U., & Saglam, H.

(2017). A determination of the quality

of life of children and adolescents with

type 1 diabetes and their parents.

International Journal of Nursing

Sciences, 4(2), 94–98. doi: 10.1016/

j.ijnss.2017.01.008

Pierce, J. S., Kozikowski, C., Lee, J. M., &

Wysocki, T. (2017). Type 1 diabetes

in very young children: a model of

parent and child influences on

management and outcomes. Pediatric

diabetes, 18(1), 17–25. https://

doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12351

Sathyananda, R., B, & Manjunath., U. (2017).

Assessment of quality of life among

the health workers of primary health

centers managed by a nongovernment

organization in Karnataka, India: A

case study. International Journal of

Health Allied Science,6(4). https://

www.ijhas.in/text.asp?2017/6/4/240/

220518

Siboni, F, S., A., Z., Atashi, V., Alipour, M., &

Khatooni, M. (2019). Quality of Life in

Different Chronic Diseases and Its

Related Factors. International journal

of preventive medicine, 10. https://

doi.org/10 .4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_429_17

Spezia Faulkner, M., & Clark, F. S. (1998).

Quality of Life for Parents of Children

and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes.

The Diabetes Educator, 24(6), 721

727. https://doi.org/10.1177/

014572179802400607

Spore,E. (2012). The Quality of Life of Primary

Caregivers of Children with Chronic

Conditions [Doctoral dissertation,

University of Illinois]. University

Library. https://indigo.uic.edu/

articles/thesis/The Quality of Life

ofCaregivers of Children with Chronic

Conditions/10809086/1

The World Health Organization quality of life

assessment (WHOQOL): Position

paper from the World Health

Organization. (1995). Social Science

& Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0277

9536(95)00112-k

Thorsteinsson, E. B., Loi, N. M., & Rayner, K.

(2017). Self-efficacy, relationship

satisfaction, and social support: the

quality of life of maternal caregivers

of children with type 1 diabetes.

PeerJ,23(5). https://doi.org/10.7717/

peerj.3961

Toledano-Toledano, F., Moral de la Rubia, J.,

Nabors, L. A., Domínguez-Guedea, M.

T., Salinas Escudero, G., Rocha Pérez,

E., Luna, D., et al. (2020). Predictors

of Quality of Life among Parents of

Children with Chronic Diseases: A

Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare,

8(4). Retrieved from http://

d x . d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 3 3 9 0 /

healthcare8040456

Uhm, J. Y., & Kim, M. S. (2020). Predicting

Quality of Life among Mothers in an

Online Health Community for Children

with Type 1 Diabetes. Children (Basel,

Switzerland), 7(11). https://doi.org/

10.3390/children7110235.

Vehik, K., Hamman, R. F., Lezotte, D., Norris,

J. M., Klingensmith, G., Bloch, C.,

Rewers, M., & Dabelea, D. (2007).

Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes

in 0- to 17-year-old Colorado youth. Diabetes care, 30(3), 503–509. https:/

/doi.org/10.2337/dc06-1837

Wiedebusch, S., Pollmann, H., Siegmund, B.,

& Muthny, F. A. (2008). Quality of life,

psychosocial strains, and coping in

parents of children with haemophilia.

Haemophilia, 14(5), 1014–1022.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365

2516.2008. 01803.x

Witt, W. P., Litzelman, K., Wisk, L. E., Spear,

H. A., Catrine, K., Levin, N., & Gottlieb,

C. A. (2010). Stress-mediated quality

of life outcomes in parents of

childhood cancer and brain tumor

survivors: a case-control study.

Quality of life research: an

international journal of quality-of-life

aspects of treatment, care and

rehabilitation,

World Health Organisation Global Report on

Diabetes. (2016). Global Report on

Diabetes. Retrieved from https://

apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/

10665/204871

Yamada, A., Kato, M., Suzuki, M., Suzuki, M.,

Watanabe, N., Akechi, T., & Furukawa,

T. A. (2012). Quality of life of parents

raising children with pervasive

developmental disorders. BMC

Psychiatry, 12(1). https://doi.org/

10.1186/1471-244x-12-119

Zhan L. (1992). Quality of life: conceptual and

measurement issues. Journal of

Advanced Nursing, 17(7), 795–800.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365

2648.1992.tb02000.x

Zhang, Y., Wei, M., Shen, N., & Zhang, Y.

(2015). Identifying factors related to

family management during the coping

process of families with childhood

chronic conditions: a multi-site study.

Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30(1),

160–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.pedn.2014.10.002

Conflict of interest: None

Role of funding source: None