Indian Journal of Health Social Work

(UGC Care List Journal)

UNDERSTANDING THE PSYCHO-SOCIAL CHALLENGES FACED BY

DEAFBLIND INDIVIDUALS: A SYSTEMATIC SCOPING REVIEW

Uttam Kumar1

& Pallavee Trivedi2

1PhD Scholar, Charutar Vidya Mandal (CVM) University, Anand, Gujarat, India

2Research Supervisor, Charutar Vidya Mandal (CVM) University, Anand, Gujarat, India

Correspondence: Uttam Kumar, E-mail: uttamkum@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Deafblindness is a complex sensory impairment that significantly impacts individuals’ psychosocial

well-being. Understanding the unique challenges faced by this population is crucial for developing

effective support services. This systematic scoping review aimed to synthesize existing research

on the psychosocial challenges experienced by deafblind individuals in India. A systematic scoping

review approach was adopted. A comprehensive search of electronic databases was conducted

to identify relevant studies. A total of 31 studies were included in the review. Data extraction

focused on study characteristics, participants, methodology, and key findings. The review identified

seven key psychosocial challenges faced by deafblind individuals: (1) social & emotional skills,

(2) psychological distress, (3) educational and occupational barriers, (4) social communication

challenges, (5) dependency and caregiving, (6) stigma and discrimination, and (7) harassment

and violence. Coping mechanisms and resilience were also explored. The findings emphasize

the need for comprehensive support services, including communication training, education,

employment opportunities, and mental health care. Further research is required to develop

culturally appropriate interventions and policies to address the specific needs of this population.

This review contributes to the growing body of knowledge on deafblindness by providing a

comprehensive overview of the psychosocial challenges faced by deafblind individuals. The findings

highlight the need for the targeted interventions and policies to improve the quality of life for

this marginalized population.

Keywords: Deafblindness, Mental health, Anxiety, Depression

INTRODUCTION

Deafblindness is a complex condition characterized by the simultaneous impairment of both hearing and vision (Kennedy & Smith, 2010). This dual sensory loss significantly impacts communication, access to information, and overall quality of life. It is crucial to recognize that deafblindness is a unique disability, distinct from the sum of its individual components (Kennedy & Smith, 2010).

The National Association for the Deaf-Blind (NADB) defines deafblindness as a combination of hearing and visual impairments so severe that it cannot be accommodated by programs solely for deaf or blind individuals (NADB, 2023). This emphasizes the specialized needs of individuals with deafblindness and the necessity for tailored educational and support services. Deafblindness can be categorized as congenital or acquired. Congenital deafblindness occurs at birth, often due to genetic factors or prenatal infections (Kennedy & Smith, 2010; World Federation of Deafblind, 2018). Acquired deafblindness develops later in life due to conditions like Usher syndrome, meningitis, or age-related degeneration (Kennedy & Smith, 2010). Further classification considers the severity and timing of sensory loss:

· Congenital deafblindness: Individuals born with both impairments require intensive support from early intervention.

· Deafblindness with residual vision: Those born deaf or hard of hearing who later lose sight often rely on remaining visual cues.

· Deafblindness with residual hearing: Individuals born blind who later experience hearing loss can benefit from auditory cues.

· Late-onset deafblindness: Acquired deafblindness in adulthood presents unique challenges due to previous independence.

Each type of deafblindness presents distinct challenges and requires specific strategies for communication and daily living. Therefore, each category necessitates tailored support and interventions to optimize the individual’s quality of life. Deafblindness, a complex sensory impairment, presents unique challenges for individuals, significantly impacting their psychosocial well-being. There are studies on psychosocial consequences of deafblind individuals; however, are scattered.

Deafblindness is a complex condition characterized by the simultaneous impairment of both hearing and vision (Kennedy & Smith, 2010). This dual sensory loss significantly impacts communication, access to information, and overall quality of life. It is crucial to recognize that deafblindness is a unique disability, distinct from the sum of its individual components (Kennedy & Smith, 2010).

The National Association for the Deaf-Blind (NADB) defines deafblindness as a combination of hearing and visual impairments so severe that it cannot be accommodated by programs solely for deaf or blind individuals (NADB, 2023). This emphasizes the specialized needs of individuals with deafblindness and the necessity for tailored educational and support services. Deafblindness can be categorized as congenital or acquired. Congenital deafblindness occurs at birth, often due to genetic factors or prenatal infections (Kennedy & Smith, 2010; World Federation of Deafblind, 2018). Acquired deafblindness develops later in life due to conditions like Usher syndrome, meningitis, or age-related degeneration (Kennedy & Smith, 2010). Further classification considers the severity and timing of sensory loss:

· Congenital deafblindness: Individuals born with both impairments require intensive support from early intervention.

· Deafblindness with residual vision: Those born deaf or hard of hearing who later lose sight often rely on remaining visual cues.

· Deafblindness with residual hearing: Individuals born blind who later experience hearing loss can benefit from auditory cues.

· Late-onset deafblindness: Acquired deafblindness in adulthood presents unique challenges due to previous independence.

Each type of deafblindness presents distinct challenges and requires specific strategies for communication and daily living. Therefore, each category necessitates tailored support and interventions to optimize the individual’s quality of life. Deafblindness, a complex sensory impairment, presents unique challenges for individuals, significantly impacting their psychosocial well-being. There are studies on psychosocial consequences of deafblind individuals; however, are scattered.

OBJECTIVE

Objective of this review is to synthesize existing research on the psychosocial experiences and their coping strategies used by deafblind individuals.

Objective of this review is to synthesize existing research on the psychosocial experiences and their coping strategies used by deafblind individuals.

METHOD

Design A systematic scoping review (Peter et al., 2015) was employed with an objective to map and synthesize evidence on psychosocial experiences of deafblind persons, their coping strategies and provide strategic recommendations. An initial search of Indian databases yielded a limited number of empirical studies. Given the diverse nature of available research, a traditional evidence hierarchy was deemed unsuitable. Such an approach would have restricted the review’s scope, excluding valuable practitioner knowledge and user perspectives. Recognizing the growing importance of user perspectives in systematic reviews (Pawson et al., 2003; Rutter et al., 2010; Gough et al., 2012), a systematic scoping review was adopted with an emphasis on rigour, inclusivity, and transparency in the search and synthesis processes.

Design A systematic scoping review (Peter et al., 2015) was employed with an objective to map and synthesize evidence on psychosocial experiences of deafblind persons, their coping strategies and provide strategic recommendations. An initial search of Indian databases yielded a limited number of empirical studies. Given the diverse nature of available research, a traditional evidence hierarchy was deemed unsuitable. Such an approach would have restricted the review’s scope, excluding valuable practitioner knowledge and user perspectives. Recognizing the growing importance of user perspectives in systematic reviews (Pawson et al., 2003; Rutter et al., 2010; Gough et al., 2012), a systematic scoping review was adopted with an emphasis on rigour, inclusivity, and transparency in the search and synthesis processes.

Date Source and Search Strategy

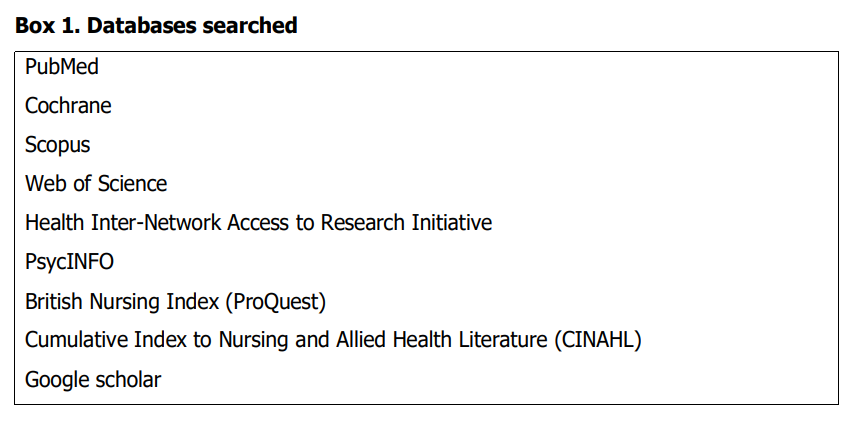

To comprehensively capture the evidence base, a search encompassing both scientific and grey literature was conducted between April 2013 and May 2024 across nine electronic databases. Box 1 provides details of scientific databases employed in this evidence synthesis.

To comprehensively capture the evidence base, a search encompassing both scientific and grey literature was conducted between April 2013 and May 2024 across nine electronic databases. Box 1 provides details of scientific databases employed in this evidence synthesis.

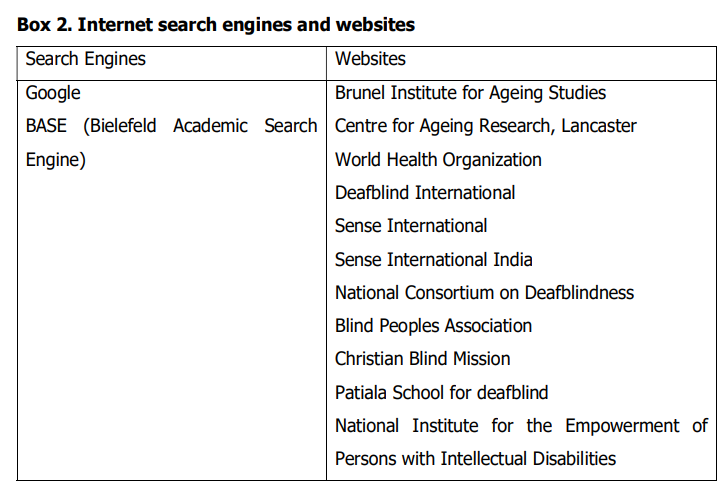

Grey literature included dissertations, theses, blogs, service provider websites, and relevant reports. Box 2 provides details of internet search carried out for grey literature.

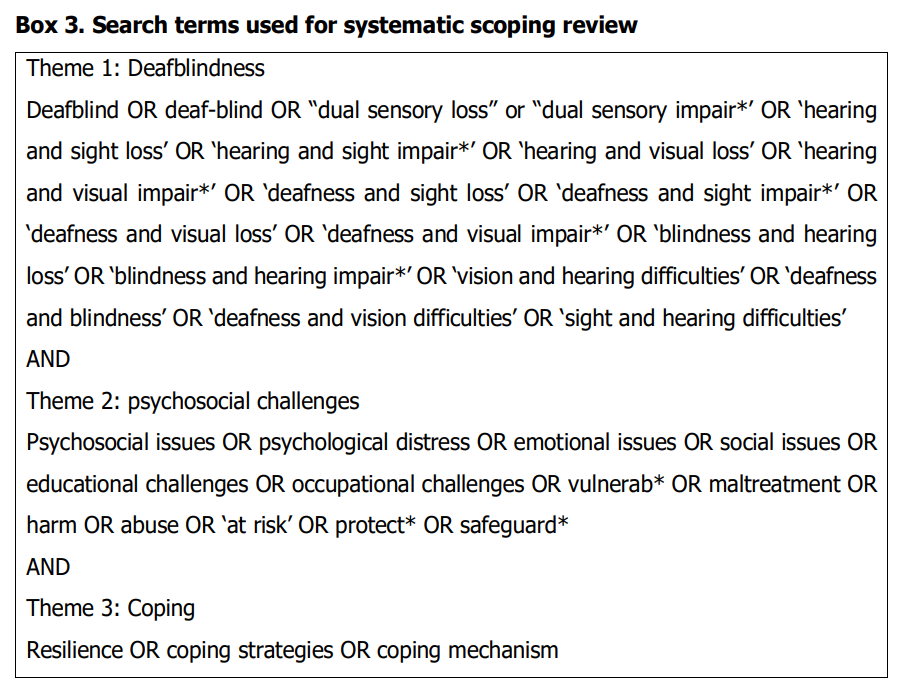

Search terms were based on key concepts drawn from the review question and its

context. Search terms were developed in three thematic domains “deafblindness,”

“psychosocial challenges,” and, resilience and coping strategies. Box 3 presents search

terms used for the systematic scoping review.

Selection of studies

Inclusion criteria focused on studies exploring the psychosocial aspects of deafblindness and their coping with psychosocial challenges. Exclusion criteria included studies primarily focused on medical or educational interventions without addressing psychosocial challenges, studies related only to those with single sensory impairment, records available in other than English language and records without full-text access. Literature search was carried out by two independent reviewers and the conflict was resolved by the senior evidence synthesis expert.

Inclusion criteria focused on studies exploring the psychosocial aspects of deafblindness and their coping with psychosocial challenges. Exclusion criteria included studies primarily focused on medical or educational interventions without addressing psychosocial challenges, studies related only to those with single sensory impairment, records available in other than English language and records without full-text access. Literature search was carried out by two independent reviewers and the conflict was resolved by the senior evidence synthesis expert.

Data extraction

Two reviewers separately extracted the data

using a standardized data extraction form,

and one reviewer confirmed the results. Study

characteristics (author, year of publication,

country), study design, sample size, patient

demographics, psychosocial experiences,

coping strategies, recommendations were

taken from each included study or research.

Appraisal and synthesis of selected studies

To ensure methodological rigor, included

studies were initially appraised using the

TAPUPAS framework (Pawson et al., 2003),

assessing transparency –is it open to

scrutiny?, accuracy –is it well grounded?,

purposiveness– is it fit for purpose?, utility–

is it fit for use?, propriety– is it legal and

ethical?, accessibility– is it intelligible?, and

specificity– does it meet source-specific

standards?. Given the limited quantity of highquality research, a pragmatic approach

prioritizing relevance over methodological

stringency was adopted (Killick & Taylor, 2009;

Ploeg et al., 2009). An interpretive synthesis

approach was employed to understand the

complex experiences of deafblind individuals

(Bryman, 2008). This method involved indepth analysis of the included studies to

identify key themes and patterns, while also

considering the limitations and biases within

the research (Fisher et al. 2006). Drawing on

principles of critical interpretive

synthesis (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006), rather

than being a determiner of whether study or

record should be included or excluded, critique

of the literature is offered within the

synthesis.

RESULTS

criteria. Of the total records included in the review, about 11 records were primary studies, and others included websites (7), reviews (6), reports (3), thesis (2), and blogs (2). Primary studies were observational studies around psychosocial experiences of deafblind persons, and coping responses. The findings highlighted seven psychosocial challenges, namely, social and emotional skills, psychological distress, educational and occupational barriers, social communication challenges, dependency and caregiving, stigma and discrimination, harassment and violence. Figure 1 presents psychosocial challenges reported in existing literature.

criteria. Of the total records included in the review, about 11 records were primary studies, and others included websites (7), reviews (6), reports (3), thesis (2), and blogs (2). Primary studies were observational studies around psychosocial experiences of deafblind persons, and coping responses. The findings highlighted seven psychosocial challenges, namely, social and emotional skills, psychological distress, educational and occupational barriers, social communication challenges, dependency and caregiving, stigma and discrimination, harassment and violence. Figure 1 presents psychosocial challenges reported in existing literature.

Social and Emotional skills

Deafblind individuals face significant challenges in developing social and emotional skills, often requiring direct teaching to achieve a sense of emotional security and identity. Without the ability to acquire these skills incidentally, as most children do, those with congenital deafblindness are slow to develop the necessary competencies for a fulfilling life. The establishment of basic trust and emotional security within consistent, loving relationships is crucial, as is the ability to recognize and express one’s feelings appropriately (Rees, 2007). Deafblind individuals often experience profound isolation and loneliness due to communication barriers and limited social interaction (Jaiswal, et al., 2018).

Deafblind individuals face significant challenges in developing social and emotional skills, often requiring direct teaching to achieve a sense of emotional security and identity. Without the ability to acquire these skills incidentally, as most children do, those with congenital deafblindness are slow to develop the necessary competencies for a fulfilling life. The establishment of basic trust and emotional security within consistent, loving relationships is crucial, as is the ability to recognize and express one’s feelings appropriately (Rees, 2007). Deafblind individuals often experience profound isolation and loneliness due to communication barriers and limited social interaction (Jaiswal, et al., 2018).

Psychological distress

Deafblind individuals experience disproportionately high rates of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and reduced self-esteem (Arcos et al., 2023; Jaiswal et al., 2022). Social isolation, stemming from communication barriers and limited social interaction, significantly contributes to these mental health challenges (Bodsworth et al., 2011; Sahoo et al., 2021). The psychological impact of deafblindness extends to experiencing isolation and barriers in accessing mental health services.

Deafblind individuals experience disproportionately high rates of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and reduced self-esteem (Arcos et al., 2023; Jaiswal et al., 2022). Social isolation, stemming from communication barriers and limited social interaction, significantly contributes to these mental health challenges (Bodsworth et al., 2011; Sahoo et al., 2021). The psychological impact of deafblindness extends to experiencing isolation and barriers in accessing mental health services.

Psychological distress

Deafblind individuals experience disproportionately high rates of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and reduced self-esteem (Arcos et al., 2023; Jaiswal et al., 2022). Social isolation, stemming from communication barriers and limited social interaction, significantly contributes to these mental health challenges (Bodsworth et al., 2011; Sahoo et al., 2021). The psychological impact of deafblindness extends to experiencing isolation and barriers in accessing mental health services.

Deafblind individuals experience disproportionately high rates of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and reduced self-esteem (Arcos et al., 2023; Jaiswal et al., 2022). Social isolation, stemming from communication barriers and limited social interaction, significantly contributes to these mental health challenges (Bodsworth et al., 2011; Sahoo et al., 2021). The psychological impact of deafblindness extends to experiencing isolation and barriers in accessing mental health services.

Educational and Occupational Barriers

Access to education and employment remains limited for deafblind individuals in India (Jaiswal et al., 2020; Jaiswal et al., 2022). The absence of inclusive educational and vocational opportunities perpetuates a cycle of poverty and dependence, further exacerbating psychosocial difficulties. As reported by World Federation of Deafblind in 2018, persons with deafblindness in the UK reported devoid of educational and occupational opportunities. This lack of inclusion can lead to low self-esteem and economic hardship.

Access to education and employment remains limited for deafblind individuals in India (Jaiswal et al., 2020; Jaiswal et al., 2022). The absence of inclusive educational and vocational opportunities perpetuates a cycle of poverty and dependence, further exacerbating psychosocial difficulties. As reported by World Federation of Deafblind in 2018, persons with deafblindness in the UK reported devoid of educational and occupational opportunities. This lack of inclusion can lead to low self-esteem and economic hardship.

Communication Challenges

Effective communication is fundamental to social interaction and well-being. Deafblind individuals encounter substantial barriers in developing and maintaining relationships due to communication challenges (McDonnall et al., 2017; Preisler, 2005). This isolation can lead to feelings of loneliness and frustration.

Effective communication is fundamental to social interaction and well-being. Deafblind individuals encounter substantial barriers in developing and maintaining relationships due to communication challenges (McDonnall et al., 2017; Preisler, 2005). This isolation can lead to feelings of loneliness and frustration.

Dependency and Caregiving

Many deafblind individuals rely on caregivers for daily living activities, leading to a sense of dependency and loss of autonomy (Hersh, 2013). This can negatively impact their selfesteem and mental health.

Many deafblind individuals rely on caregivers for daily living activities, leading to a sense of dependency and loss of autonomy (Hersh, 2013). This can negatively impact their selfesteem and mental health.

Stigma and Discrimination

Deafblind individuals often experience stigma and discrimination, which can exacerbate their psychosocial challenges and limit their access to support services (Arcous et al., 2024; Bodsworth et al, 2011). Misunderstandings about the capabilities of deafblind individuals can result in lowered expectations and fewer opportunities for social interaction. For instance, the use of derogatory terms like “deaf and dumb” persists, which not only is incorrect but also harmful, as it perpetuates the false notion that deafblind individuals lack intellectual capabilities (Thomas, 2013).

Deafblind individuals often experience stigma and discrimination, which can exacerbate their psychosocial challenges and limit their access to support services (Arcous et al., 2024; Bodsworth et al, 2011). Misunderstandings about the capabilities of deafblind individuals can result in lowered expectations and fewer opportunities for social interaction. For instance, the use of derogatory terms like “deaf and dumb” persists, which not only is incorrect but also harmful, as it perpetuates the false notion that deafblind individuals lack intellectual capabilities (Thomas, 2013).

Harassment and violence

Deafblind individuals face a heightened risk of harassment and violence due to their unique vulnerabilities and societal misconceptions. Their sensory impairments can make it difficult to perceive or respond to threats, leaving them particularly susceptible to abuse. Physical abuse, including hitting and restraint, is prevalent (Arcous et al., 2024; Jaiswal et al., 2018). Psychological abuse like intimidation and emotional manipulation further compounds their suffering (Arcous et al., 2024; Bodsworth et al., 2018; McDonnall, et al., 2011).

Deafblind individuals face a heightened risk of harassment and violence due to their unique vulnerabilities and societal misconceptions. Their sensory impairments can make it difficult to perceive or respond to threats, leaving them particularly susceptible to abuse. Physical abuse, including hitting and restraint, is prevalent (Arcous et al., 2024; Jaiswal et al., 2018). Psychological abuse like intimidation and emotional manipulation further compounds their suffering (Arcous et al., 2024; Bodsworth et al., 2018; McDonnall, et al., 2011).

Psychosocial toll on family and care

takers of deafblind individuals

The emotional toll for the family members of deafblind individuals includes feelings of resentment, exclusion, and anxiety due to perceived inequities within the family dynamics (Huus, et al., 2022). Siblings of deafblind may also face social embarrassment and anxiety about their future roles in supporting their sibling with deafblindness (Arcous et al., 2024). The family dynamics, in return, impact the mental health of persons with deafblindness.

The emotional toll for the family members of deafblind individuals includes feelings of resentment, exclusion, and anxiety due to perceived inequities within the family dynamics (Huus, et al., 2022). Siblings of deafblind may also face social embarrassment and anxiety about their future roles in supporting their sibling with deafblindness (Arcous et al., 2024). The family dynamics, in return, impact the mental health of persons with deafblindness.

Coping Strategies and Resilience

Despite facing numerous challenges, deafblind individuals demonstrate remarkable resilience and develop coping strategies. These include strong support networks, adaptive communication techniques, and a positive outlook on life (Cameron, 2017; Cameron et al., 2017). Despite adversity, deafblind individuals exhibit remarkable resilience. They develop adaptive strategies, such as strong support networks, effective communication techniques, and a positive outlook, to navigate challenges (Cameron, 2017; Cameron et al., 2017). Strategies used by deafblind persons are described as follow:

Despite facing numerous challenges, deafblind individuals demonstrate remarkable resilience and develop coping strategies. These include strong support networks, adaptive communication techniques, and a positive outlook on life (Cameron, 2017; Cameron et al., 2017). Despite adversity, deafblind individuals exhibit remarkable resilience. They develop adaptive strategies, such as strong support networks, effective communication techniques, and a positive outlook, to navigate challenges (Cameron, 2017; Cameron et al., 2017). Strategies used by deafblind persons are described as follow:

. Communication and community support:

Despite significant communication barriers, deafblind individuals employ various strategies to connect with others. These include the use of tactile sign languages, braille, and assistive technology to facilitate communication and social interaction (Warnicke, et al., 2022). Developing strong support networks, including family, friends, and support groups, is crucial for maintaining emotional well-being and accessing necessary resources (Sahoo, et al., 2021).

Despite significant communication barriers, deafblind individuals employ various strategies to connect with others. These include the use of tactile sign languages, braille, and assistive technology to facilitate communication and social interaction (Warnicke, et al., 2022). Developing strong support networks, including family, friends, and support groups, is crucial for maintaining emotional well-being and accessing necessary resources (Sahoo, et al., 2021).

.Independence and Self-Advocacy:

Fostering independence is a key coping strategy for deafblind individuals. Developing self-advocacy skills enables them to assert their needs, access support services, and challenge discriminatory attitudes (Sproston, 2021). Assistive technology plays a vital role in enhancing independence by providing tools for communication, mobility, and daily living activities (Dyzel et al., 2020).

Fostering independence is a key coping strategy for deafblind individuals. Developing self-advocacy skills enables them to assert their needs, access support services, and challenge discriminatory attitudes (Sproston, 2021). Assistive technology plays a vital role in enhancing independence by providing tools for communication, mobility, and daily living activities (Dyzel et al., 2020).

.Positive Mindset and Problem-Solving:

Maintaining a positive outlook and developing effective problem-solving skills are essential for coping with the challenges of deafblindness. Focusing on strengths, setting achievable goals, and seeking opportunities for personal growth can contribute to overall resilience (Allison, n.d.).

Maintaining a positive outlook and developing effective problem-solving skills are essential for coping with the challenges of deafblindness. Focusing on strengths, setting achievable goals, and seeking opportunities for personal growth can contribute to overall resilience (Allison, n.d.).

.Resilience and Adaptation:

Deafblind

individuals demonstrate exceptional

resilience by adapting to their

circumstances and finding creative

solutions to overcome obstacles. Their

ability to find joy and meaning in life,

despite adversity, is a testament to their

strength and determination (Allison, n.d.).

Insights on support services and professional development

A global survey involving 324 professionals across 36 countries, conducted by Monash University (Willoughby et al., 2023), highlighted the current state of support services for deafblind individuals. The study revealed significant gaps in professional development, with high costs and limited training opportunities as primary barriers. This lack of formal education exacerbates workforce shortages in the field, impacting the quality of support provided to the deafblind community.

A global survey involving 324 professionals across 36 countries, conducted by Monash University (Willoughby et al., 2023), highlighted the current state of support services for deafblind individuals. The study revealed significant gaps in professional development, with high costs and limited training opportunities as primary barriers. This lack of formal education exacerbates workforce shortages in the field, impacting the quality of support provided to the deafblind community.

DISCUSSION

Deafblind individuals encounter a myriad of psychosocial challenges stemming from their unique sensory impairment. Isolation, communication barriers, and dependency on caregivers significantly impact their quality of life (McDonnell, Kennedy, & Murphy, 2017; Preisler, 2005). Moreover, stigma, discrimination, and limited access to support services further exacerbate these difficulties (Arcos et al., 2024; Bodsworth et al., 2011). Despite these challenges, deafblind individuals exhibit remarkable resilience. They develop coping mechanisms such as strong support networks, effective communication strategies, and a positive outlook (Cameron & Cameron, 2017). However, the effectiveness of these strategies is often hindered by limited access to specialized support services. Research indicates that a significant proportion of service providers lack the necessary expertise to address the unique needs of deafblind individuals (McDonnell et al., 2017). Communication issues, cultural misunderstandings, and the rural distribution of populations contribute to the difficulties faced by deafblind individuals in accessing mental health support. Approximately 43.2% of service providers have noted the absence of professionals with the necessary expertise as a primary challenge. Additionally, the high costs and limited resources available to agencies exacerbate these accessibility issues (Mcdonall, et al., 2017). These underscore the urgent need for enhanced training and standardized credentialing for professionals, as well as the importance of community and personal resilience in managing the complexities of deafblindness.

Deafblind individuals encounter a myriad of psychosocial challenges stemming from their unique sensory impairment. Isolation, communication barriers, and dependency on caregivers significantly impact their quality of life (McDonnell, Kennedy, & Murphy, 2017; Preisler, 2005). Moreover, stigma, discrimination, and limited access to support services further exacerbate these difficulties (Arcos et al., 2024; Bodsworth et al., 2011). Despite these challenges, deafblind individuals exhibit remarkable resilience. They develop coping mechanisms such as strong support networks, effective communication strategies, and a positive outlook (Cameron & Cameron, 2017). However, the effectiveness of these strategies is often hindered by limited access to specialized support services. Research indicates that a significant proportion of service providers lack the necessary expertise to address the unique needs of deafblind individuals (McDonnell et al., 2017). Communication issues, cultural misunderstandings, and the rural distribution of populations contribute to the difficulties faced by deafblind individuals in accessing mental health support. Approximately 43.2% of service providers have noted the absence of professionals with the necessary expertise as a primary challenge. Additionally, the high costs and limited resources available to agencies exacerbate these accessibility issues (Mcdonall, et al., 2017). These underscore the urgent need for enhanced training and standardized credentialing for professionals, as well as the importance of community and personal resilience in managing the complexities of deafblindness.

Strategies to promote positive health

and mental wellbeing

Effective communication is foundational for the well-being of deafblind individuals. Simple acts like greeting and farewell can significantly impact their daily lives, reducing anxiety and fostering a sense of connection (Bond et al., 2010). Inclusive communication strategies, adapted to their specific needs, are essential for promoting social interaction and reducing isolation (Smith et al., 2015). Creating inclusive environments extends beyond physical accessibility. Societal attitudes and practices must evolve to accommodate the needs of deafblind individuals. This involves raising awareness, challenging stereotypes, and implementing supportive policies (Jones et al., 2018). Access to healthcare, particularly mental health services, is crucial. While initiatives like India’s ‘Kiran’ helpline offer support, accessibility remains a challenge due to communication barriers and a shortage of specialized professionals (Sharma et al., 2022). Bridging this gap requires increased training and support for healthcare providers to effectively address the unique needs of the deafblind community. By fostering inclusive communities, providing accessible healthcare, and promoting mental well-being, we can significantly enhance the quality of life for deafblind individuals. There is a need to address both the psychosocial and environmental barriers and the social attitudes that contribute to the isolation of deafblind individuals, communities can foster a more inclusive and supportive environment This not only benefits those with deafblindness but also enriches the community as a whole by embracing diversity and promoting mutual understanding.

Effective communication is foundational for the well-being of deafblind individuals. Simple acts like greeting and farewell can significantly impact their daily lives, reducing anxiety and fostering a sense of connection (Bond et al., 2010). Inclusive communication strategies, adapted to their specific needs, are essential for promoting social interaction and reducing isolation (Smith et al., 2015). Creating inclusive environments extends beyond physical accessibility. Societal attitudes and practices must evolve to accommodate the needs of deafblind individuals. This involves raising awareness, challenging stereotypes, and implementing supportive policies (Jones et al., 2018). Access to healthcare, particularly mental health services, is crucial. While initiatives like India’s ‘Kiran’ helpline offer support, accessibility remains a challenge due to communication barriers and a shortage of specialized professionals (Sharma et al., 2022). Bridging this gap requires increased training and support for healthcare providers to effectively address the unique needs of the deafblind community. By fostering inclusive communities, providing accessible healthcare, and promoting mental well-being, we can significantly enhance the quality of life for deafblind individuals. There is a need to address both the psychosocial and environmental barriers and the social attitudes that contribute to the isolation of deafblind individuals, communities can foster a more inclusive and supportive environment This not only benefits those with deafblindness but also enriches the community as a whole by embracing diversity and promoting mutual understanding.

Implications for future research,

programme and practice

The findings of this review underscore the urgent need for comprehensive and targeted interventions to address the multifaceted psychosocial challenges faced by deafblind individuals. Fostering collaboration among researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and deafblind communities is crucial for developing effective solutions. Capacity building initiatives for healthcare providers, educators, and social workers are essential to enhance their knowledge and skills in supporting deafblind individuals. Research should focus on developing and evaluating interventions that are tailored to the specific needs and preferences of different subgroups within the deafblind community. Advocating for policies that promote inclusion and accessibility for deafblind individuals is essential. Research should highlight the policy gaps and recommend evidence-based policy interventions to address the challenges faced by this population. Longitudinal qualitative studies can help gain a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of deafblind individuals. Exploring their coping mechanisms, resilience factors, and support needs over time will provide valuable insights for developing effective interventions. It is imperative to evaluate existing support services for deafblind individuals to assess their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. This includes examining the impact of these services on the quality of life, independence, and social participation of beneficiaries.

The findings of this review underscore the urgent need for comprehensive and targeted interventions to address the multifaceted psychosocial challenges faced by deafblind individuals. Fostering collaboration among researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and deafblind communities is crucial for developing effective solutions. Capacity building initiatives for healthcare providers, educators, and social workers are essential to enhance their knowledge and skills in supporting deafblind individuals. Research should focus on developing and evaluating interventions that are tailored to the specific needs and preferences of different subgroups within the deafblind community. Advocating for policies that promote inclusion and accessibility for deafblind individuals is essential. Research should highlight the policy gaps and recommend evidence-based policy interventions to address the challenges faced by this population. Longitudinal qualitative studies can help gain a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of deafblind individuals. Exploring their coping mechanisms, resilience factors, and support needs over time will provide valuable insights for developing effective interventions. It is imperative to evaluate existing support services for deafblind individuals to assess their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. This includes examining the impact of these services on the quality of life, independence, and social participation of beneficiaries.

CONCLUSION

The study illuminates psychosocial challenges faced by deafblind individuals, experiences of their family members and caretakers, and their coping strategies. It highlights the unique hurdles deafblind people confront daily, from the profound isolation compounded by public misconceptions to the pressing need for specialized support services that accommodate their complex communication and mobility requirements. The study highlights the importance of resilience, community support, and innovative technological aids in enhancing their quality of life. It is a clarion call for enhanced accessibility, increased awareness, and comprehensive support to empower deafblind individuals, enabling them to lead fulfilling lives and contribute to their communities fully. Prospective research is warranted in the area of prevalence of mental health problems, linkages to healthcare services and social protection schemes and quality of life.

The study illuminates psychosocial challenges faced by deafblind individuals, experiences of their family members and caretakers, and their coping strategies. It highlights the unique hurdles deafblind people confront daily, from the profound isolation compounded by public misconceptions to the pressing need for specialized support services that accommodate their complex communication and mobility requirements. The study highlights the importance of resilience, community support, and innovative technological aids in enhancing their quality of life. It is a clarion call for enhanced accessibility, increased awareness, and comprehensive support to empower deafblind individuals, enabling them to lead fulfilling lives and contribute to their communities fully. Prospective research is warranted in the area of prevalence of mental health problems, linkages to healthcare services and social protection schemes and quality of life.

REFERENCES

Allison, S. (n.d.). Glimpse of our world. Inspiring stories of deafblind persons. h t t p : / / dbiyn.deafblindinternational.org/ wpcontent/uploads/2018/09/A-Glimpseof-Our-World.pdf Arcous, M., Potier, R., & Dumet, N. (2024). Psychological and social consequences of deafblindness for siblings: a systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1102206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1102206 Bodsworth, S. M., Clare, I. C., Simblett, S. K., & Deafblind UK. (2011). Deafblindness and mental health: Psychological distress and unmet need among adults with dual sensory impairment. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 29(1), 6-26. Bond, J., & Smith, K. (2010). Communication and well-being in deafblind adults. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 15(2), 123-135. Bryman A. (2008). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cameron, J. (2017). The Impact of Stress on Brain Architecture and Resilience., 2017 Texas Symposium on Deafblindness, Austin, TX. Cameron, J., Zeedyk, S., Blaha, R., Brown, D., van den Tillaart, B., (2017). What Harvard Research Means for Children with Deafblindness, 2017 Texas Symposium on Deafblindness, Austin, TX. Dixon-Woods M., Cavers D., Agarwal S. et al. (2006) Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology 6, 35–48. Dyzel, V., Oosterom-Calo, R., Worm, M., & Sterkenburg, P. S. (2020, September). Assistive technology to promote communication and social interaction for people with deafblindness: a systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 5, 578389. https:// w w w . f r o n t i e r s i n . o r g / j o ur n a ls / e d u c a t i o n / a r t i c l e s / 1 0 . 3 3 8 9 / feduc.2020.578389/full Fisher M., Qureshi H., Hardyman W. & Homewood J. (2006) Using Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews: Older People’s Views of Hospital Discharge. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Gough D., Oliver S. & Thomas J. (2012) An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. Sage, London. Hersh, M. (2013). Deafblind people, communication, independence, and isolation. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 18(4), 446-463. Huus, K., Sundqvist, A. S., Anderzén-Carlsson, A., Wahlqvist, M., & Björk, M. (2022). Living an ordinary life – yet not: the everyday life of children and adolescents living with a parent with deafblindness. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 17(1), 2064049. https:// d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 8 0 / 17482631.2022.2064049 Jaiswal, A., Aldersey, H., Wittich, W., Mirza, M., & Finlayson, M. (2018). Participation experiences of people with deafblindness or dual sensory loss: A scoping review of global deafblind literature. PloS one, 13(9), e0203772. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0203772 Jaiswal, A., Aldersey, H., Wittich, W., Mirza, M., & Finlayson, M. (2022). Factors that influence the participation of individuals with deafblindness: A qualitative study with rehabilitation service providers in India. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 40(1), 3-17. Jones, M., & Harris, L. (2018). Inclusive communities for deafblind individuals: A systematic review. Disability & Society, 33(1), 1-20. Kennedy, J., & Smith, C. (2010). Deafblindness: A complex condition. Publisher. Killick C. & Taylor B.J. (2009) Professional decision making on elder abuse: systematic narrative review. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 21 (3), 211– 238. McDonnall, M. C., Crudden, A., LeJeune, B. J., & Steverson, A. C. (2017). Availability of mental health services for individuals who are deaf or deafblind. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 16(1), 1– 13. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1536710X.2017.1260515 Miles, B. (2008). Overview on deaf-blindness. DB-LINK: The National Information Clearinghouse on Children Who Are Deaf-Blind. Miles, Barbara., Riggio, Marianne. (1999). Remarkable Conversations A Guide to Developing Meaningful Communication with Children and Young Adults Who Are Deafblind, Published by Perkins School for the Blind, 175 North Beacon Street, Watertown, Massachusetts. National Association for the Deaf-Blind (NADB). (2023). National Consortium on Deaf-Blindness. (2007). Children who are deaf-blind. https://www.nationaldb.org/infocenter/deaf-blindness-overview/ National Center on Deaf-Blindness. (2019). National child count of children and youth who are deaf-blind report. Pawson R., Boaz A., Grayson L., Long A. & Barnes C. (2003) Types and Quality of Knowledge in Social Care. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Ploeg J., Fear J., Hutchison B., MacMillan H. & Bolan G. (2009) A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 21 (3), 187–210. Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 141- 146. Preisler, G. (2005). Development of communication in deafblind children. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 7(1), 41-62. Rees C. (2007). Childhood attachment. The British Journal of General Practice: the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 57(544), 920–922. h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 3 3 9 9 / 096016407782317955 Rutter D., Francis J., Coren E. & Fisher M. (2010) SCIE Systematic Research Reviews: Guidelines, 2nd edn. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Sahoo, S., Naskar, C., Singh, A., Rijal, R., Mehra, A., & Grover, S. (2021). Sensory deprivation and psychiatric disorders: Association, assessment and management strategies. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 44(5), 436-444. Sharma, S., Patel, R., & Desai, A. (2022). Mental health services for deafblind individuals in India: A needs assessment. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 59(1), 115- 128. Sproston, S. (2021). Speaking out: My perspective on self-advocacy as a person who is blind. https://cobd.ca/ 2 0 2 1 / 0 5 / 2 9 / s p e a k i n g – o u t – m y – perspective-on-self-advocacy-as-aperson-who-is-blind/ Thomas, D. J. (2013). Not a hearing loss, a deaf gain: Power, self-naming, and the Deaf community. Old Dominion University. Warnicke, C., Wahlqvist, M., AnderzénCarlsson, A., & Sundqvist, A. S. (2022). Interventions for adults with deafblindness – an integrative review. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1594. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08958-4 Willoughby, Louisa; Hlavac, Jim; Hunter, Eleanore (2023). Deafblind Professionals Report_final.pdf. Monash University. Report. https:// doi.org/10.26180/23536398.v1 World Federation of Deafblind. (2018). Deafblindness and health. https:// w f d b . e u / w f d b – r e p o r t – 2 0 1 8 / deafblindness-and-health.

Allison, S. (n.d.). Glimpse of our world. Inspiring stories of deafblind persons. h t t p : / / dbiyn.deafblindinternational.org/ wpcontent/uploads/2018/09/A-Glimpseof-Our-World.pdf Arcous, M., Potier, R., & Dumet, N. (2024). Psychological and social consequences of deafblindness for siblings: a systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1102206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1102206 Bodsworth, S. M., Clare, I. C., Simblett, S. K., & Deafblind UK. (2011). Deafblindness and mental health: Psychological distress and unmet need among adults with dual sensory impairment. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 29(1), 6-26. Bond, J., & Smith, K. (2010). Communication and well-being in deafblind adults. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 15(2), 123-135. Bryman A. (2008). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cameron, J. (2017). The Impact of Stress on Brain Architecture and Resilience., 2017 Texas Symposium on Deafblindness, Austin, TX. Cameron, J., Zeedyk, S., Blaha, R., Brown, D., van den Tillaart, B., (2017). What Harvard Research Means for Children with Deafblindness, 2017 Texas Symposium on Deafblindness, Austin, TX. Dixon-Woods M., Cavers D., Agarwal S. et al. (2006) Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology 6, 35–48. Dyzel, V., Oosterom-Calo, R., Worm, M., & Sterkenburg, P. S. (2020, September). Assistive technology to promote communication and social interaction for people with deafblindness: a systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 5, 578389. https:// w w w . f r o n t i e r s i n . o r g / j o ur n a ls / e d u c a t i o n / a r t i c l e s / 1 0 . 3 3 8 9 / feduc.2020.578389/full Fisher M., Qureshi H., Hardyman W. & Homewood J. (2006) Using Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews: Older People’s Views of Hospital Discharge. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Gough D., Oliver S. & Thomas J. (2012) An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. Sage, London. Hersh, M. (2013). Deafblind people, communication, independence, and isolation. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 18(4), 446-463. Huus, K., Sundqvist, A. S., Anderzén-Carlsson, A., Wahlqvist, M., & Björk, M. (2022). Living an ordinary life – yet not: the everyday life of children and adolescents living with a parent with deafblindness. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 17(1), 2064049. https:// d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 0 8 0 / 17482631.2022.2064049 Jaiswal, A., Aldersey, H., Wittich, W., Mirza, M., & Finlayson, M. (2018). Participation experiences of people with deafblindness or dual sensory loss: A scoping review of global deafblind literature. PloS one, 13(9), e0203772. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0203772 Jaiswal, A., Aldersey, H., Wittich, W., Mirza, M., & Finlayson, M. (2022). Factors that influence the participation of individuals with deafblindness: A qualitative study with rehabilitation service providers in India. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 40(1), 3-17. Jones, M., & Harris, L. (2018). Inclusive communities for deafblind individuals: A systematic review. Disability & Society, 33(1), 1-20. Kennedy, J., & Smith, C. (2010). Deafblindness: A complex condition. Publisher. Killick C. & Taylor B.J. (2009) Professional decision making on elder abuse: systematic narrative review. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 21 (3), 211– 238. McDonnall, M. C., Crudden, A., LeJeune, B. J., & Steverson, A. C. (2017). Availability of mental health services for individuals who are deaf or deafblind. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 16(1), 1– 13. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1536710X.2017.1260515 Miles, B. (2008). Overview on deaf-blindness. DB-LINK: The National Information Clearinghouse on Children Who Are Deaf-Blind. Miles, Barbara., Riggio, Marianne. (1999). Remarkable Conversations A Guide to Developing Meaningful Communication with Children and Young Adults Who Are Deafblind, Published by Perkins School for the Blind, 175 North Beacon Street, Watertown, Massachusetts. National Association for the Deaf-Blind (NADB). (2023). National Consortium on Deaf-Blindness. (2007). Children who are deaf-blind. https://www.nationaldb.org/infocenter/deaf-blindness-overview/ National Center on Deaf-Blindness. (2019). National child count of children and youth who are deaf-blind report. Pawson R., Boaz A., Grayson L., Long A. & Barnes C. (2003) Types and Quality of Knowledge in Social Care. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Ploeg J., Fear J., Hutchison B., MacMillan H. & Bolan G. (2009) A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 21 (3), 187–210. Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 141- 146. Preisler, G. (2005). Development of communication in deafblind children. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 7(1), 41-62. Rees C. (2007). Childhood attachment. The British Journal of General Practice: the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 57(544), 920–922. h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 3 3 9 9 / 096016407782317955 Rutter D., Francis J., Coren E. & Fisher M. (2010) SCIE Systematic Research Reviews: Guidelines, 2nd edn. Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Sahoo, S., Naskar, C., Singh, A., Rijal, R., Mehra, A., & Grover, S. (2021). Sensory deprivation and psychiatric disorders: Association, assessment and management strategies. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 44(5), 436-444. Sharma, S., Patel, R., & Desai, A. (2022). Mental health services for deafblind individuals in India: A needs assessment. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 59(1), 115- 128. Sproston, S. (2021). Speaking out: My perspective on self-advocacy as a person who is blind. https://cobd.ca/ 2 0 2 1 / 0 5 / 2 9 / s p e a k i n g – o u t – m y – perspective-on-self-advocacy-as-aperson-who-is-blind/ Thomas, D. J. (2013). Not a hearing loss, a deaf gain: Power, self-naming, and the Deaf community. Old Dominion University. Warnicke, C., Wahlqvist, M., AnderzénCarlsson, A., & Sundqvist, A. S. (2022). Interventions for adults with deafblindness – an integrative review. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1594. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08958-4 Willoughby, Louisa; Hlavac, Jim; Hunter, Eleanore (2023). Deafblind Professionals Report_final.pdf. Monash University. Report. https:// doi.org/10.26180/23536398.v1 World Federation of Deafblind. (2018). Deafblindness and health. https:// w f d b . e u / w f d b – r e p o r t – 2 0 1 8 / deafblindness-and-health.

Conflict of interest: None

Role of funding source: None